Signs that Tunisia’s political elites want to abandon its transitional justice process is leading some to rue a missed chance for the truth-telling and reform the country bitterly needs.

Seven years after the revolution, Tunisia’s transitional justice process is on life support. The country’s most powerful politicians have given clear signals that they want little to do with the process.

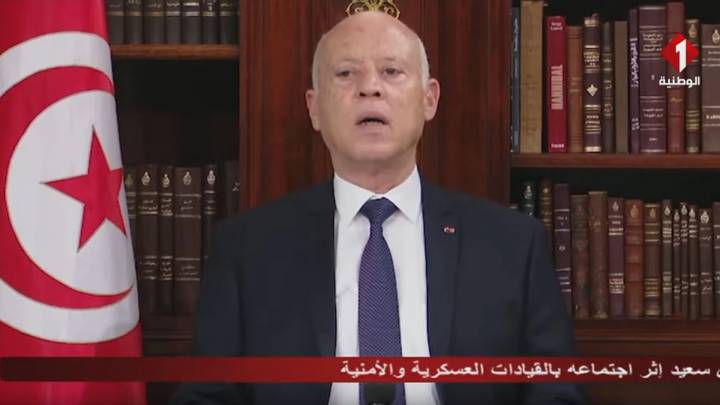

“I wanted to turn quickly the page of the past that we must rise above. When I returned to state affairs, this time as president, I said one must from now on look to the future,” Tunisia’s President Mohamed Beji Caid Essebsi told local media, referring to his controversial amnesty law designed to shield civil servants who served under the old regime of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.

The president and his family practically composed a mafia that looted the country.

Meanwhile, even some of those in favour of a rigorous transitional justice process are critical of the truth commission tasked with carrying out the work. L’Instance Vérité et Dignité (IVD) is highly politicised, inefficient and not very transparent, says Achref Aouadi, President of anti-corruption NGO I Watch. “We need to have a discussion about how to save what is left of the transitional justice process, because it is not safe either in the hands of the government or the truth commission.”

At stake in this debate is justice for victims of more than fifty years of single-party rule, the historical memory of the country since its independence in 1956, and potentially its future social and economic well-being. The high-water mark for transitional justice process came with the first public hearings in 2016. Broadcast live on television and online, it was the first time Tunisians heard testimony from ordinary people describing human rights injustices endured during more than 50 years of single-party rule, rather than learning the facts from reports of human rights activists.

“Tunisians were finally facing their painful past legacy, and they were directly listening to victims,” says Salwa El Gantri, head of the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) in Tunisia. She describes the hearings as “a kind of explosion” in Tunisian society. Significant too was that not only victims spoke but also perpetrators. Imed Trabelsi, nephew of Leila Trebelsi – the president’s wife and part of the family that systematically looted the country during Ben Ali’s rule – spoke about the system of corruption that dominated the country’s economy. “Despite the fact that most Tunisians knew that this was taking place, it had a strong impact to have the person himself describe all this,” says El Gantri.

But even then there were signs of a lack of buy-in from the upper echelons of political power, with the presidents of the republic, parliament and government all absent. There are questions of whether any could be implicated – Essebsi served under both Ben Ali and Habib Bourguiba – but the symbolism of their no-show was significant. “The feedback from victims [we received] was that it would have been a golden opportunity for them to attend, to show not only that they support the process of truth-seeking and justice in Tunisia, but as a kind of indirect apology for what the state did as political violence to its citizens,” says El Gantri.

The public hearings coincided with the Tunisia 2020 Conference, an economic showcase for the government designed to solicit economic investment from international players including wealthy Gulf states, and to deliver the message that Tunisia is open for business.

Politicians at the time suggested that the hearings should be cancelled, for fear that the testimony of the victims would upset the investment conference. Yet El Gantri believes that a show of willingness by Tunisia to confront past crimes committed by its rulers – both human rights violations such as torture, and economic crimes – would send a positive signal to international investors.

“The president and his family practically composed a mafia that looted the country. If Tunisia after the revolution chose to investigate those economic crimes and combat corruption, normally this would give more confidence and faith to foreign investors to come here, because they know their rights will be respected as long as they are in Tunisia.”

The question of how to create more accountability and transparency has not been raised.

It’s one of the many arguments that the detractors of transitional justice have deployed against the process. As in the words of President Essebsi, the most common complaint is that Tunisia needs to look forward and not back. Another view is that the process only relates to a few corrupt individuals: what Tunisia needs is wholesale reform of its bureaucracy, economy, healthcare and education. A significant factor too is that many ordinary Tunisians are not engaged with the process; some lack a complete idea of what is at stake, believing it is relevant only to victims of the regimes of Ben Ali and Habib Bourguiba.

There are also concrete signs that the transitional justice process has had a chilling effect on the economy. Prior to the revolution, the system for gaining administrative approval for purchasing land or opening a factory more or less worked; after it, everything was thrown into disarray, according to Mouna Ben Halima, CEO of La Badira, a luxury hotel in Hammamet, who says civil servants turned to carrying out procedures by the book, with some regulations dating back to the French colonial era, which damaged economic growth. With bureaucrats fearing prosecution for decisions by a future government, they simply made no decisions – a situation that parallels Egypt post-revolution, says Issandr El Amrani, North Africa Director of the International Crisis Group.

Foreign investors have been discouraged from opening factories and other job-creating facilities, while many wealthy Tunisians are investing their money overseas rather than creating enterprises at home, in part due to the bureaucratic logjam – lost opportunities that Tunisia can ill afford. Meanwhile, despite improvements for foreign investors, including a better security situation, low-level corruption in Tunisia is now widespread and many international companies are choosing Morocco instead, a “more streamlined investment environment” according to Allison Wood, a consultant at advisory firm Control Risks.

What this government is not getting is that American and European countries are not only accountable to governments in the soil of their companies, [they’re accountable] internationally.

The president’s solution to this “blackmail-like paralysis” is the amnesty for civil servants signed into law last month, says El Amrani. Originally meant to grant amnesty to a broader group including businessmen, its scope was narrowed after a backlash from civil society groups and opposition politicians. Critics of the law see it as a betrayal of the revolution to simply grant an amnesty to these people without justice, and believe it will push the country towards the old system where the economy was politically controlled.

While El Amrani is sympathetic to the need to address civil service paralysis, he believes granting amnesty without conditions and without reforms to prevent future corruption is giving out a blank cheque. “The question of how to create more accountability and transparency has not been raised. If the law had included such steps, it would have been a better law.”

Essebsi’s amnesty law may also create uncertainty for the business community. Tunisia’s transition to a full democracy remains incomplete. Most notably, the country still lacks a constitutional court where the actions of the executive can be challenged. In interviews, several CSOs say the amnesty law will be the first piece of legislation they mount a challenge against once the court is in place, raising the spectre of its being one day struck down.

NGO I Watch frequently receives calls from international businesses or governments wanting to carry out due diligence on potential business partners. What should the answer be for these cases, wonders Aouadi: “[Do I say] he’s corrupt but he got an amnesty, so I don't know?” Foreign investors cannot take these kinds of risks, he says. “What this government is not getting is that American and European countries are not only accountable to governments in the soil of their companies, [they’re accountable] internationally. You have to give them a fair and competitive ecosystem where they can safely invest.”

No justice, says victim’s brother

Redha Barakati sits on the edge of a cream-white sofa in his living room. Seated beside him is his brother Nabil Barakati – a framed drawing of him, that is. Nabil, an activist, was tortured to death by police in 1987, during the later years of Habib Bourguiba’s regime. Nabil’s body was dumped in a drain near the police station, placed with a gun to make it look like he had escaped and committed suicide. His face was beaten to a pulp. “His flesh was red like sausages,” Redha told Tunisia’s Truth and Dignity Commission (l’Instance Vérité et Dignité, IVD) last November as family and friends looked on.

Redha asked that May 8, the day of Nabil’s death, be designated a national day against torture, and that the police station where he was killed be turned into a museum and office space created for civil society organisations working with human rights. But like many, he is not optimistic about the process. “There is no transitional justice today in Tunisia,” he says emphatically.

Meanwhile, the apparent intention of Tunisia’s political elites to cut the legs out from under the transitional justice process is leaving many to rue the opportunities they saw for reform of the economy. Activist group Manich Msamah (‘I will not forgive’) regularly holds noisy demonstrations in downtown Tunis to protest the lack of progress. Taib Henchir, a member, points out the damage caused by public service hiring driven by family connections or bribery rather than merit. Elsewhere, Rabie Razgallah, the asssociate director of Dacima Consulting, a medical software company based in Tunis, believes greater openness in public tenders will benefit innovative sectors such as medical technology – prior to the revolution, it was almost impossible for young companies without connections to win public contracts.

It is also a question of the truth about Tunisia’s history. Aouadi sees in the transitional justice process a chance to expose the workings of Ben Ali-era cronyism and help Tunisia safeguard against future illegal practices. “We need to understand where the loopholes are and prevent them taking place again. I want to understand how Ben Ali used to conduct tax evasion, how he used to ship money abroad, how he used to get away with it.”

The IVD is expected to release its report in May, which could potentially re-energise public debate. ICTJ’s El Gantri believes the report will be a marking point. “The final report will be extremely important, because the unspoken will finally be documented and written, and there not only for us now but for the next generations. It will encourage citizens to hold the government accountable on guarantees of no repetition.” Nevertheless, as far as concrete reforms go, “We will still also need political will to implement a minimum of the recommendations that will be issued on economic crimes in Tunisia,” she says.

For Tunisia’s future, with rising public frustration some fear an uprising, while others worry that ordinary citizens, disenfranchised by the lack of progress on key economic issues through the democratic process, could support a slide back into authoritarianism.

Ahmed Seddik, an MP and parliamentary leader of the left-wing Popular Front party, believes that without accountability and transparency the country will “repeat the same mistakes, excesses and crimes of the past”. While Seddik is not expecting the issue to be central in the parliamentary elections in 2019, he believes it is very much present in the subconscious of ordinary people. He predicts a chance of a dangerous uprising this winter: “Any social explosion in the future will be the result of the absence of transitional justice.”

Tunisia’s informal crisis

The country’s informal economy – business owners who evade taxes or carry out illegal activities such as smuggling – is flourishing, shrinking the government’s tax base and putting further pressure on its finances. At the same time, more than 50 per cent of the government’s budget is spent on the public sector wage bill.

“What we see now is that the government has no solution to propose other than to raise taxes on [formal sector] businesses to compensate for the informal economy that it is not able to fight,” says Walid Bel Hadj Amor, a businessman and Vice President of Institut Arabe de Chefs d’Enterprises (IACE), a Tunis-based think tank. This in turn will encourage more companies to leave for the informal sector, he believes.

This article is a joint collaboration between zenith, Organisation Volonté et Citoyenneté (Will and Citizenship Organization) and Institute for the Study of Human Rights at Columbia University in the City of New York. This research work is supported by the Robert Bosch Foundation.