In 2014, Lebanon took the step of requiring its banks to invest in its knowledge economy, sparking rapid growth in the tech sector. Now other regional governments are looking to emulate Circular 331–but should they be wary of unintended consequences?

From his office on the eighth-floor of the glimmering Beirut Digital District (BDD) building, Rami Hallal, co-founder of Blink My Car, an on-demand car washing service, reflects on their journey from a tiny shop next to his house to an office within the heart of Beirut’s flourishing tech scene. “We saved money, but we also get so many benefits by being here,” he says, leaning back in his chair in the open plan office space they share with three other startups. Along with the networking opportunities and support and development they receive, there’s also the distinct buzz of being in the centre of a booming tech ecosystem – Lebanon’s newest, and perhaps only, rapidly growing industry.

It wasn’t always this way. Traditionally, tech companies in Lebanon have had to struggle with poor infrastructure and the small market size, while vital funding opportunities were also extremely limited. This changed in August 2014, when Lebanon took a bold step, with a missive from its central bank requiring the country’s commercial banks to invest in its knowledge economy. Engineered by the Banque du Liban (BDL), the directive – Circular 331 – has the potential to direct as much as $400 million to be invested into the knowledge economy. To mitigate the risk for local lenders, the central bank guarantees 75 per cent of the bank investments – up to certain limits – while companies that receive investment are required to spend at least 80 per cent of it in Lebanon. While it was unfamiliar territory for the country’s high-street lenders, most have made money available, either investing directly or through a handful of investment funds approved by the BDL. There’s no doubt that Circular 331 was the catalyst for this flow of investment, said Nassib Ghobril, chief economist at Byblos Bank, one of the country’s main high-street lenders in an interview in July. “Banks would not have considered this sector, and anyway were not allowed to invest into the capital of companies due to the regulations.”

Today, if you want $50,000-100,000 in Lebanon it’s much harder than raising $1-2 million.

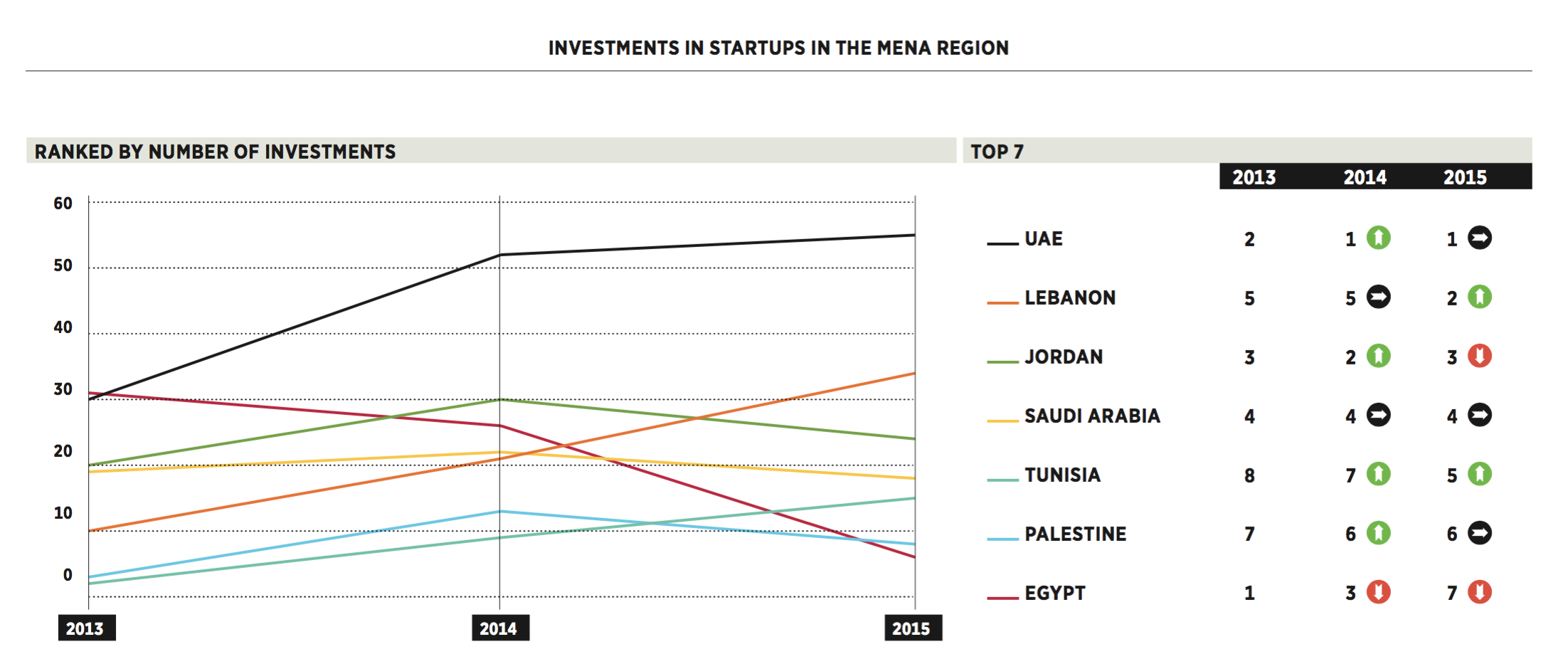

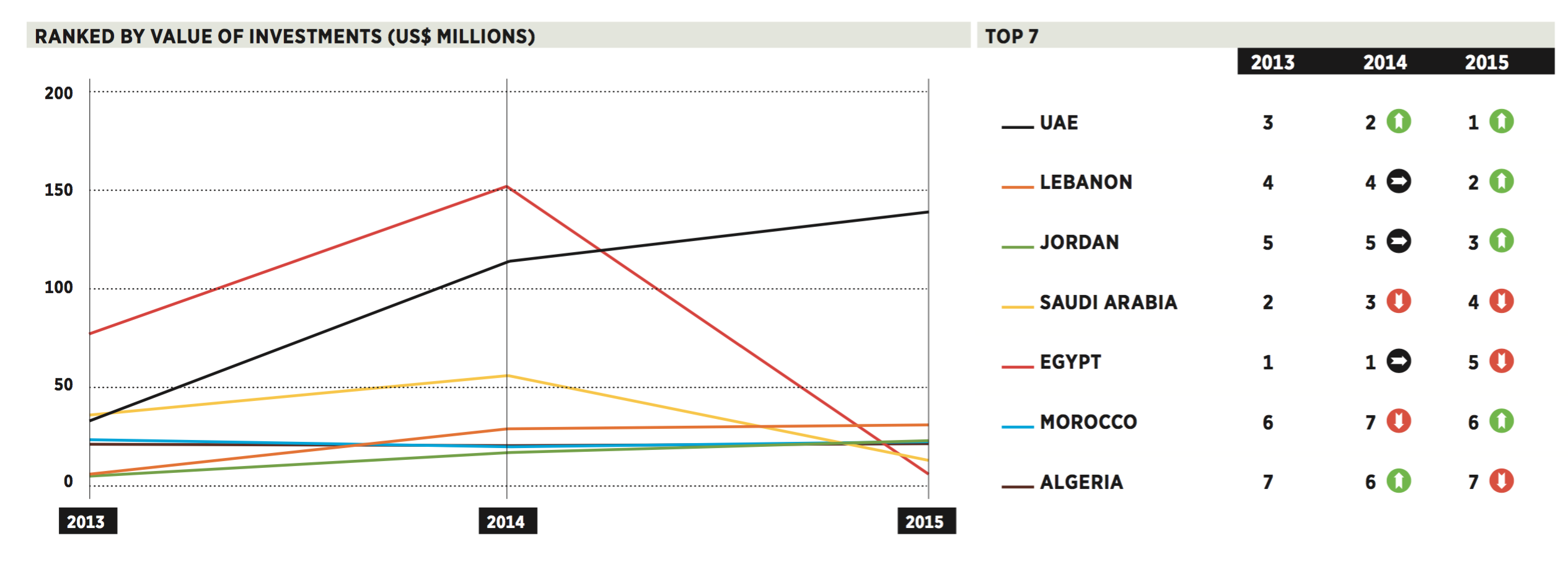

The data shows a sudden leap in investments – in 2013 and 2014, Lebanon was 5th and 4th place respectively for number and value of investment deals in the Arab region, but jumped to second overall in 2015, according to research by ArabNet, a startup incubator and media company – and venture capitalists who are directing much of the banks’ investment into the sector believe Lebanon is on the cusp of building something big. “Circular 331 is a one-time chance to build the credibility of this asset class. It’s new in Lebanon and the region, so there is a feeling of shared responsibility,” explains Hala Fadel, a partner at Leap Ventures – one of the VC firms that has benefited from the wave of funds.

It comes at a difficult time for Lebanon: in recent years the country of around 4.5 million people has been hit by a severe economic slowdown with drops in tourism, investment and growth. This is partly caused by the fallout from the civil war that has raged for more than five years in neighbouring Syria and the country’s political paralysis.

Lebanon has the highest proportion of refugees per capita in the world, with some 1.1 million Syrians now sheltering there, adding to the strain on already stretched institutions and finances. The country had experienced a protracted political stalemate - over two years without a president, until the appointment of Michel Aoun in October - during which the parliament failed to legislate on key issues. In addition, political disagreement with the wealthy Gulf countries – who resent Hezbollah’s influence in the country – have seen them cancel aid, as well as raising the spectre of falling remittances, a vital source of income for Lebanon. “The economy is not on the verge of collapse – nor are public finances, the monetary stability or the Lebanese currency – but the economy is stagnating,” said Ghobril.

A private market solution

The boldness of Circular 331 means policy-makers around the region are paying close attention, with countries including Jordan and Saudi Arabia thought to be planning similar measures. As a centralised policy directive it certainly holds appeal, especially with countries in MENA looking to entrepreneurship to boost sagging economic growth and combat youth unemployment. Other countries have already launched analogous initiatives, says Omar Christidis, the CEO of ArabNet, pointing to measures such as Kuwait’s National Fund for SME Development, “but Circular 331 has moved implementation faster than most”.

He believes that the strength of Lebanon’s initiative is that private banks and venture capitalists are making the investment decisions, rather than public sector entities. “While the Kuwait fund wasannounced a while back, they are still setting themselves up; perhaps the difference [in Lebanon] is that BDL has decided to do this at arm’s length.”

As well as loosening the funding scene, Circular 331 also created and financed a number of accelerator and support initiatives. BDD was one, and within its walls lies another – the UK Lebanon Tech Hub (UKLebHub), a joint initiative between the British government and BDL. An incubator for new startups, as well as a co-working space and training academy, UKLebHub has been helping foster and grow the tech sector for the past two years. That means that even tech companies not receiving financing directly from the $400 million pool are still benefiting from the new ecosystem projects through BDL-supported initiatives, says Lama Zaher of UKLebHub. While the country’s notoriously slow Internet speeds remain an issue, there are some improvements, including a fibre optic connection to BDD in May – the only place in the country to have it.

“A few years ago the Internet was debilitating. You just weren’t participating in the world the way you should be,” says Nasri Atallah, a partner at Keeward, a digital production company that he’lps establish brands, startups and creatives with everything from content to online presence. Keeward has been operating for nearly 10 years, with offices around the world and 150 employees. They have a number of major projects – notably Bookwitty, a book sharing and selling platform that distributes millions of volumes a year worldwide. Atallah believes that while some of the infrastructure issues, such as the Internet, have made only limited improvements, the landscape for tech startups today is almost unrecognisable compared with when they started operating.

“There’s no longer one or two success stories, there’s an above average number of great ideas coming out of Lebanon,” says Atallah. Everything is coming together at once, he adds: funding, mentorship, accelerators, spaces and talent.

Ecosystem boost

Despite the sector’s optimism, there’s also recognition that Lebanon still has a long way to go. “You can feel that the money is there but the basic pillars for the ecosystem aren’t yet,” says Hallal. He believes that with time this will develop. “No one can expect to have a beautiful ecosystem just because you have a circular that says ‘we have the money here.’” There are also questions about the availability of talent. With Dubai’s established reputation as a global business powerhouse, talented and experienced individuals are time and again choosing the emirate as their headquarters, says Walid Hanna, founder and managing partner at Middle East Venture Partners (MEVP).

In Dubai, MEVP has invested in startups founded by nationals from all over the world, whereas in Lebanon it is mostly local startups that are looking internationally. Entrepreneurs in Beirut, while impressive, are simply not experienced in taking companies to the big leagues, while international talent is likely to look elsewhere. “Why would an Australian, American or German come to Lebanon? You’ve got ISIS just [on the border] and Hezbollah right there. The money does not solve this,” says Hanna.

With skilled coders and developers in short supply, training and up-skilling is seen by many as necessary for creating a viable, long-term industry. At Keeward, demand for talent forced Atallah and his team to get creative. At one point they realised they were hiring a lot of coders from Zahleh, a mid-sized town in Lebanon’s largely pastoral Bekaa Valley. Keeward’s response was to partner with a local university and set up a satellite office in the area; it now employs dozens of locals.

Meanwhile, UKLebHub hopes to contribute to the creation of 25,000 jobs by 2025, says Zaher. Despite only counting 200 new jobs created through their projects in the last year, she believes that over the next four to six years the number will grow exponentially as the quantity and size of tech sector firms increase. A number of trainers and mentors are also looking to establish training programmes for youth in Tripoli, one of the poorest areas in Lebanon, a sign that the effects of Circular 331 are extending beyond Beirut and into areas with fewer formal employment opportunities.

Over-valuation worries

Interventions in a private market are never without risk, and in Beirut today there are concerns that the sudden rush of money into the tech scene has caused over-valuations as cashed-up investors chase a handful of quality tech companies. At MEVP, Hanna was among the first to establish a 331-compliant fund, and by being first off the blocks was able to scoop up some of the best deals in town – including Keeward – for their $70m Impact fund. Since then, the number of attractive propositions has dried up; in the last six months alone they’ve been outbid by competitor funds five times, said Hanna. “The money is overkill, valuations are going through the roof and we’re suffering. We will not play this valuation bidding game. We have a very serious investment committee that would prevent us [over-bidding].”

Namek Zu’bi, managing partner at Silicon Badia, a VC with offices in Amman and New York, sees a similar story. The last time they were on the verge of closing a deal with a Lebanese tech company, a local VC fund came in at the last moment and grossly outbid them. Yet much of this activity is occurring around Series A, where VC funds invest in companies that are somewhat established and have a proven business model. Early stage startups on the look-out for smaller investments from accelerators, angel investors and seed funders are struggling, meaning the pipeline of development is too narrow and too many investors are chasing a dearth of viable opportunities around Series A.

“Today, if you want $50,000-100,000 in Lebanon it’s much harder than raising $1-2 million,” says Christidis. A recent ArabTech digital investment report found that Lebanon currently has seven venture capital firms offering mid-level investment, compared to just four early stage investors at different levels. The BDL approval process meant these established funds were the first to receive Circular 331 money.

Leap Venture’s Fadal suggests that a perception of ease made mid-sized venture capital and Series A funding attractive, whereas the risk at seed level and the sheer size of investment needed at Series B made both of these less interesting for those with money (Leap Ventures only do Series B funding). “There is no overvaluation in seed funding because there’s not enough money, and there’s no overvaluation in Series B because there isn’t enough money either,” she said. With a new batch of funds jockeying for approval this year, this dynamic may change, and there are hopes of more early stage activity. Yet Hanna is worried that the BDL may not make the right call in this area. More needs to be done for early stage funding, he believes. MEVP and a number of other investors have clubbed together to found Speed, a major accelerator for new startups.

Other investors highlight that easier access to funding risks artificially supporting companies that would otherwise fail. Building early stage companies is “super hard and the probability of success is very, very low”, says Zu’bi. Meanwhile, in the spirit of the ‘fail fast’ mantra, tech entrepreneurs are expected to bounce back from mistakes, either pivoting their enterprise or founding a new one – a process of natural selection that makes the entire ecosystem stronger over time. This was already difficult in Lebanon, where wrapping up a failed entity can take years because of antiquated business laws, creating an ongoing liability for investors and entrepreneurs. Circular 331 – “dumping money in a disorganised fashion” – may also prevent this cycle from happening naturally, believes Zu’bi. “It may actually artificially support or prolong the inevitable reality, so that when the music does stop – when companies run out of money, or exits don’t materialise or are too few – the damage may be much greater if expectations aren’t realistic from the beginning. People forget how hard it is to make it in this industry. It’s not for everyone.”

With overvaluations, the world ‘bubble’ is already on some lips. New measures could help bring more order to the market. Rami Jisr, chairman of the board at B&Y Division One fund, has suggested that providing greater transparency in offers made by funds could help prevent a bubble. In late 2014, a BDL representative proposed the formation of an equity trading system, which would bring liquidity and transparency to the market. This proposal may have faltered due to political or financial disagreements, according to one source. Lebanon’s haphazard governance means that this proposal could be resolved overnight and suddenly appear, or it could just simply fade into memory (BDL did not respond to an interview request).

Certainly, the biggest determinant of Circular 331’s success will be the quality of the companies that receive funding, and in turn whether these can prove their value through an exit – being bought by another, larger tech company, an IPO, or other exit activity. If worries about overvaluation are correct, this could mean diminished returns from exits that will reduce returns on bank and fund investments.

Despite his concerns, Hanna remains positive about the outlook for their Impact fund. Given current market conditions, they’re expecting a return of around two times investment (for comparison, he expects returns of around 3 to 3.5 on MEVP’s main regional funds). He doesn’t believe Lebanon is currently in a tech bubble, but the risk is there. “The circular is working, it’s doing miracles. But this overflow of money today creates serious issues.”