While Syrians that flee to Jordan or surrounding countries can take solace from having fled the horrors of war, difficulties in accessing labour markets or starting their own enterprise mean they have to subsist on aid.

Ahmad Kassar enjoys not standing out in the scramble around him. The 53-year-old family father takes one of the few free seats in the waiting room in a social centre opened for Syrian refugees in Amman. While many of his 150 fellow countrymen are visibly nervous, Kassar, dressed in an oversized raincoat, waits calmly for his appointment with Care International, one of the humanitarian organisations operating in Jordan which provides cash and housing assistance to Syrians. It’s not what Kassar ever intended - before the civil war he had built up a successful business manufacturing soap in Aleppo, exporting around the world. Now his factory and his home stand in ruins.

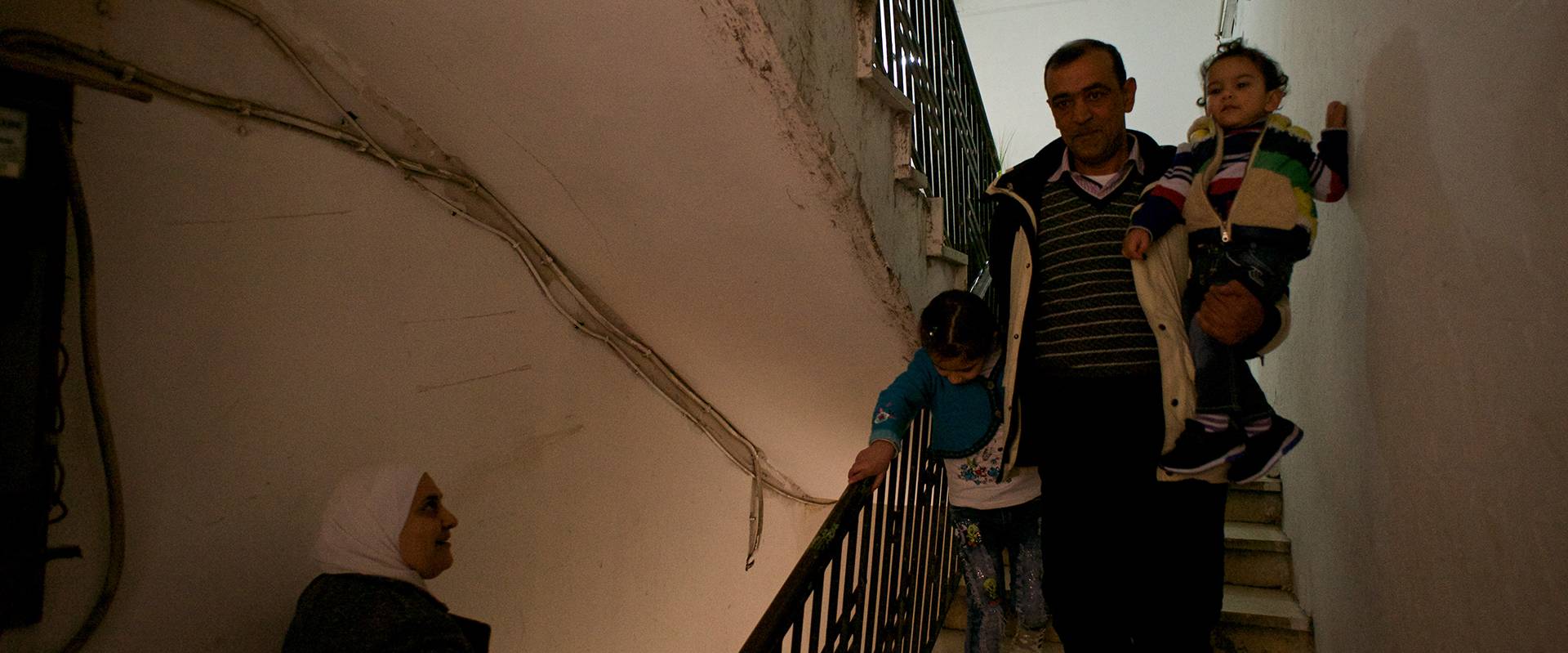

In Lebanon, Turkey and Jordan someone like me has got no chance to wait for the end of the war under somewhat dignified living conditions. It is comforting just for once to not to be left all alone with his problems, he later says quietly on the way back to the two bedroom apartment in which his family of five has been living for one year. How much longer they will live there, they do not know. Their savings are fast spent, a common reality for many Syrians who left their country for the Hashemite kingdom. Still, he is unwilling to despair, says Kassar. “I’ve had my fair share of experience in building up a business from the ground as an independent retailer, in 2010 we produced 15 tonnes of pure organic soap, exporting it to the whole world.”

For more than 10 years Kassar managed a soap factory in Aleppo, employing 20 workers, without the help of any loans or connections to the regime. “I even exported to Germany, natural soap and shampoos made in Aleppo without any additives are well known all around the world.”

Even when the war arrived in Aleppo and his shop in the old town went up in flames, fleeing didn’t cross the minds of the Kassar family. “Decades of work were put into my four storey house, my factory and a small farm outside of the city. All that my employees and I could think of was how to rebuild the shop and repair the damages on the factory caused by bombs once the conflict ended.”

Then in early 2015 a militia took over the vacant house of a neighbour who had fled because he was rumoured to have worked for the Assad regime. Kassar could instantly tell that the bearded men were dangerous - filled with hatred and without any sign of an organised command structure. They kept up with the production of soap only a few hundred metres away, even as the fights on the outskirts of the city started closing in on them. “Soap was much needed,” he says, before emphasising that he has never taken sides with any of the civil war parties.

His employees ignored the rebel group’s call for a citywide general strike against the government. “Only a few things were still produced in Aleppo. It was our personal mission to continue working, our way of showing resistance since the beginning of the war.”

The tough road

Some of the commanders from the neighbouring house accused Kassar of being the leader of strike breakers and therefore collaborating with the regime. In the same night that they received the death threat, the family escaped to Amman using hidden paths and saving their lives by paying protection money at seven different control points.

After friends helped them out with finding an apartment in the eastern part of the city, Kassar went on the search for a business partner to distribute his soap recipes. “I developed a special mixture of herbs and oils that can be applied to target allergies and fight against bacteria.”

But as a Syrian, Kassar had to try to partner with a local Jordanian – otherwise he would face steep capital requirements to start a business on his own. But Jordanian distribution partners declined working with them because the natural ingredients of the soap made the product too expensive for the Jordanian market.

Back in the apartment, Miriam Kasser says that the family won’t be able to run for more than half a year on the savings of aid money from Care."We had a good life before the war, living standards in Aleppo were way higher than in Amman.”

The Kassar family is not alone. No one is sure exactly how many Syrians are presently in Jordan - it may be as high as 1.5 million - while more than 600,000 are officially registered as refugees with the UNHCR, but for many access to work is problematic. Syrians have not been able to work in most jobs, while recently agriculture, construction or manufacturing have been opened up to them as part of Jordan’s compact this year with the international community. Those who work illegally risk being taken to one of the camps such as Za’atari or Azraq or even deported back to Syria if they are caught - one reason that child labour among the Syrian population in Jordan and Lebanon is high, since children are unlikely to be suspected.

Would-be entrepreneurs also face difficulties in Jordan’s small and un-dynamic economy: the profit margin of many traditional Syrian agricultural products aren’t high enough or there is an imbalance caused by a too dominant position of the native partner.

Seeking chances in Europe

Kassar’s daughter and her boyfriend made her way to Germany over a year ago, using the Balkan route that was still open at that point. The two of them, both in their mid-twenties, found an apartment near Hamburg. In the meantime Seiline Kassar speaks German well and has picked up on violin lessons again, just like she did in Aleppo.

“In Lebanon, Turkey and Jordan someone like me has got no chance to wait for the end of the war under somewhat dignified living conditions. I don’t want any handouts, all I want is the chance to build up a company again,” he says. Will this be possible again in Aleppo one day?

Hassan shrugs his shoulders, it seems as if he never dared to really think about it. On the drive to Amman he was constantly talking about the good life he had in Aleppo before the war.

He seems shocked by his own words. “In my street alone there are now four more militia groups. The factory, my house were all demolished during the air raids. I don’t know if there is a future left there.”

Shortly before he is called to a consultation, his scratch-covered smartphone vibrates. A WhatsApp message from his daughter appears on the display. Under her picture a question pops up: “Daddy, when are you coming home to us?”

Translation by Nova Campanelli.