The extremist Islamic State group has exploited its takeover and destruction of the Palmyra military prison for its propaganda purposes. To understand why this has been so effective, one needs to look back at what happened there in the summer of 1980.

The Palmyra Massacre stands out as a dirty episode of the American Civil War. In retaliation for the abduction of a Union supporter, Colonel John McNeil had 10 Confederate prisoners of war executed on October 18, 1862. The skull of the missing man, Andrew Alsman, turned up on the banks of the Mississippi River 13 years later. The skull was preserved as a curiosity of American war history, while a stone memorial was erected in the small town of 4,000 in honour of the Confederate victims, who most likely had nothing to do with Alsman’s disappearance.

This episode is just one example of the role of historical narratives in the culture of memory surrounding traumatic and identity-building wars. Residents of Palmyra, Missouri are proud of the historic architecture and events of their town, which is located on the former border of Union and Confederacy. Local historians and journalists still debate the details and subplots of this particular legend.

Anyone in there won’t get anywhere with personal relationships or bribes.

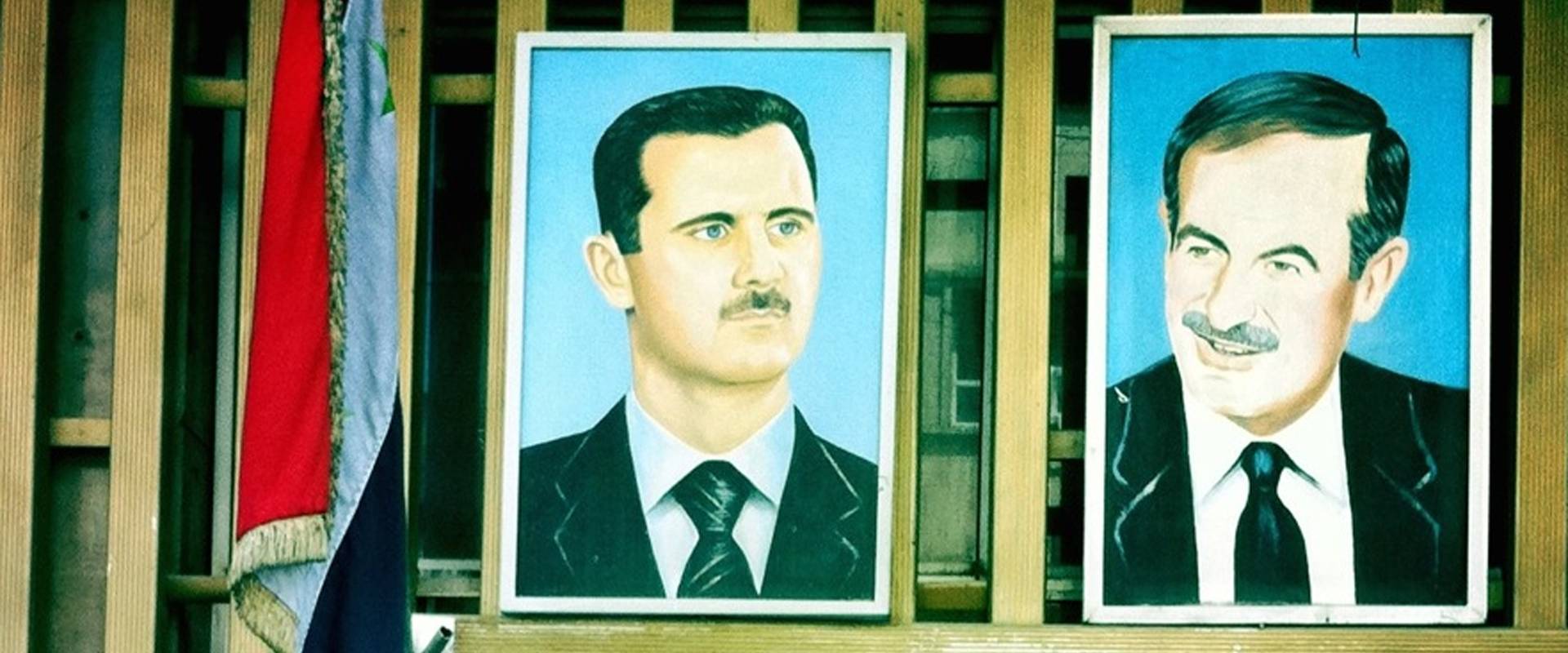

It is questionable whether any such monument will be erected for the victims of a massacre in the Missouri town’s Syrian namesake, a magnificent antique city in the desert where shadowy events took place on June 27, 1980. Officials there have shown little interest in examining what happened. Instead, it appears as if that the Assads – President Bashar al-Assad and his father, the late former President Hafiz al-Assad – have taken advantage of how deeply the massacre there has burned itself into Syria’s collective consciousness. There is little public access to information about the turn of events, something that is highlighted by the widely differing estimates on victim numbers.

Just one day before, on June 26, 1980, President Hafiz al-Assad survived an assassination attempt at the entrance to the Qasr Diyafa Palace in the Damascus district of Abu Rumaneh. The incident was the provisional highlight culmination of a series of violent acts and repressive measures, — an escalation in a war the regime had been waging for several years against Sunni insurgents, in particular the Muslim Brotherhood. A Sunni from the presidential guard killed the assassin, while an Alawite threw himself on the hand grenades, sacrificing his life for Assad.

An unexpected saviour

The fact that there was no public commemoration or public knowledge of his saviour points to the elder Assad’s policy of creating religious divisions, especially against his own community of, the Alawites. Around the time of the assassination attempt, Assad could certainly have used a Sunni martyr on his side to send a strong signal to the population. But not an Alawite.

“According to Assad’s logic, he could not benefit from owing a debt to the Alawites that would oblige him to show gratitude or make concessions,” says Habib Abu Zarr, an Alawite author and intellectual who was once close to the regime but has been publishing under this pseudonym since 2013.

Anyone who threatened the president’s life had opened the gates of hell.

Assad didn’t want to be indebted to the Alawites; but it was expedient for his leadership if the Alawites bore a collective guilt. Within hours of the attack, the regime had forged a revenge plan. It’s difficult to determine today whether the then president came up with it on his own or left it to his brother Rifaat. But it seems likely that Hafiz al-Assad applied his technique of domination through creating a general confusion and deliberately keeping his security forces in the dark. Wouldn’t it perfectly serve his purposes if his security forces took revenge, without having to take action himself? Either way, the message was the same: Anyone who threatened the president’s life had opened the gates of hell.

At 3 am on June 27th, the 40th division of the defensive cohorts or Saraya al-Difaa, were called to meet at the screening room on a Damascus military base. The Saraya was a sort of elite paramilitary corps that was partially trained by Soviet instructors and under the direct command of Rifaat al-Assad. Members differed from the conventional military not only by their uniforms and bullet-proof vests - they were also recruited almost exclusively among from the Alawite community. Major Muin Nasif, Rifaat's son-in-law, commanded the bloody mission. He allegedly even gave the soldiers a choice as to whether they wanted to participate.

Inhumane Prison Conditions

A witness later said that no one in the unit opted out. The units then left Mezzeh military airport in southeast Damascus and flew in 10 helicopters to Palmyra. They landed around 6 am, when sunlight had already begun to wash over the famous Temple of Bel and the Tetrapylon ruins.

Until 2011, Palmyra was among the most popular and spectacular destinations for ancient ruins in the Near East, if not the entire Mediterranean region. An ancient old caravan town where ancient Arabian and Roman cultures mingled, it lies next to a hilly desert landscape and a grove of date palms to which Palmyra owes not only its Latin name, but also its ancient Semitic name: Tadmor – the date grove.

Syrians used to associate this word with the splendour of the past, but now it has taken on a sinister meaning as well: The Tadmor military prison has become one of the most inhumane detention centres in the Middle East. Even back in June 1980 it was already the site of systematic torture, while conditions at the prison pointed to the explicit intent to exterminate certain inmates.

Prisoners were literally bathing in the blood of their fellow inmates.

Syrian authorities weren’t concerned with adhering to the 1977 United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, and the detention centre at Tadmor appears to have been a particular gruesome site. Survivors quoted in a 2001 Amnesty International report, as well as other sources, reported regular, sometimes daily flogging and other forms of torture. Cruel, as they were useless. Prisoners weren’t under interrogation. They were being punished. Guards beat the prisoners with iron bars and forced them to injure each other. Former prisoners also reported being forced to take blood baths, during which they were made to run a literal gauntlet. This happened mainly in winter, when they were forced to descend into an ice-cold bath with their open wounds. It was a perfidious ritual of compulsive hygiene in which they were literally bathing in the blood of their fellow inmates.

On the bureaucratic side of the prison’s activities, Amnesty International also reported a cynical legalism. When a prisoner died of torture by beatings with iron bars or blows to the head with cement blocks, for example, prison doctors would commonly describe the causes of death as “a sudden fall backwards in a dark room”, or “taking medicines not prescribed by a physician or the health officer”.

Dividing inmates by religious background

One apparently systematic method of punishment, still in use today at Syrian prisons run by the military’s secret services, is to employ captured deserters and delinquent soldiers to maltreat the other prisoners. Reports from survivors from the early 1980s also coincide with match information received by zenith more recently. In November 2014, a former employee of the Syrian Air Force’s intelligence service told a zenith source that when he entered a military intelligence detention centre in Homs that summer, prisoners were separated and treated differently according to their religious background. Sunnis accused of being insurgents or terrorists were kept in cells of just 8 to 10 square metres with up to 20 people, he said. There they suffered sleep deprivation, infectious diseases and systematic malnutrition. Prisoners also regularly suffocated because guards turned off the ventilation system.

“Anyone in there won’t get anywhere with personal relationships or bribes," said the source.

According to this source, Alawite military prisoners are also housed in this prison for various criminal offenses such as pilfering weapons and material from army stores. Their accommodations are a bit more comfortable, but like the ‘“military prisoners’” at Tadmor in the 1980s, the zenith source said that they are being forced to abuse Sunni prisoners.

Those who are particularly ambitious at this task can expect better conditions or early release. According to zenith’s source, they don’t have special torture instruments, and instead rely on their own hands and feet to strike, kick and choke their victims. Viewed cynically, this is a cost-effective approach that protects prison staff and leaves the dirty work to inmates who have plenty of time and energy to spare. But one side effect that seems to be intentional is the unrelenting hatred it foments between religious groups. According to this logic, Alawites torture Sunnis, rather than state authorities torturing alleged terrorists. This way the Alawites invite the hatred of the Sunni majority, stirring up a drive for retaliation against their enemies, regardless of how close they are to the regime.

An Example and a Deterrent

It’s undeniable that this oppressive tactic is not only based on confessional divides, but also takes advantage of existing hatred and distrust between the different religious groups. At Tadmor many of the prisoners came to die, not to serve sentences. Most of them were suspected of carrying out terrorist attacks or planning to overthrow the regime with the Muslim Brotherhood.

Virtually all the inmates of Tadmor on that June of 1980 were Sunnis. According to estimates by members of the defense cohorts, between 550 and 700 suspected terrorists were in the barracks. Later calculations put the number at as high as between 1,100 and to 2,000.

The men of the 40th and 138th divisions stormed the prison barracks with their automatic weapons and hand grenades until no one inside was moving.

The units, divided into six or seven groups of about a dozen, stormed the prison barracks with their automatic weapons and hand grenades until no one inside was moving any longer. About half an hour later, trucks brought the troops back to the landing pad. In Mezze, Major Nasif was waiting with a thank-you speech and a generous breakfast. The units had suffered one death and two injuries.

These details of the mass execution come from a source who is credible despite his participation in the incident. At the time, Isa Ibrahim Fayyad was 20 years old, and the statements of the Alawite paramilitary soldier correspond with what is known about the events at Tadmor that day, thanks in part to information and sourcing already gathered in the 1980s by French sociologist and Syria expert Michel Seurat.

Fayyad's statement appeared on February 26, 1981 in the Jordanian newspaper Al-Rayy. Jordanian security forces had arrested him and two other fighters of the “defense cohorts” in Amman, allegedly thwarting an attack on Jordanian Prime Minister Mudar Badran, who was friends with the Muslim Brotherhood and an enemy of the Assads.

Even for Syria, with its dismal human rights record, the Palmyra prison massacre of Palmyra was a particularly frightening example of state brutality. But the most striking aspect of the slaughter was the way it had the appearance of being a collective crime committed by Alawites against Sunnis.

Far-reaching repercussions

It was no accident, then, that Baath newspaper Tishrin published a “guest commentary” a few days later by President Hafiz al-Assad’s brother Rifaat. In keeping with the regime tradition, he claimed the opposite of what had actually been going on. He conjured the unity of the Syrian nation, the Arab cause, and the “resistance,”, by which he could only have meant the conflict with Israel. The “enemies of the nation”, the Muslim Brotherhood, were also “enemies of civilisation”. They "use, bend and distort Islam” for their purposes, he said.

The Palmyra massacre has never been publicly discussed in Syria under either Hafiz or Bashar al-Assad.

Rifaat also invoked the history of Syria, and how its people had stood up to the Mongols, the Mamluks, crusaders, Ottomans and European colonial powers. “We don’t want to hurt anyone and won’t take it when someone wants to hurt us.” It’s unclear who he meant by “we” – the Alawites? His Baathists? The regime?

The prison massacre looms large in the discussion of the regime’s brutality, but also the “hereditary guilt” of the Alawites. On June 26, 2011, the 31st anniversary of the massacre, a few hundred Syrians demonstrated on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, DC against repression in their home country. At the time the protesters were still waving two sets of flags: the green, white and black banner of insurgency, as and well as the red, white and black national Syrian flag that is now rather seen at pro-Assad rallies.

The Palmyra massacre has never been publicly discussed in Syria under either Hafiz or Bashar al-Assad. But the regime hasn’t seemed to mind the rumours and speculation that have circulated about the gruesome details and number of victims. This appears to be tactical. Once set in motion, the machinery of death served as an example and a deterrent to the regime’s benefit. At the same time, however, it was possible to spread a narrative in which it was not the “father of the nation,” Hafiz al-Assad, who was to blame for the massacre, but his brother Rifaat, who later fell out of favour, and a gang of over-zealous, hate-filled Alawites.

Hafiz al-Assad’s brother Rifaat and his Alawites have been painted as the “butchers of Palmyra,”, so that Hafiz could later become the victor over all of Syria.

This article first appeared in German in the 1/2015 edition of zenith. Translation by Kristen Allen.