While the international community is discussing peace initiatives for Yemen, the situation on the ground continues to fragment. An overview of who is fighting whom and why in Yemen.

The situation in Yemen is often referred to as a “quagmire”, a puzzle with no military or political solution. The prolonged conflict is a clear indicator of the existing fragmentation that plagues the country. The situation involves an increasingly powerful de-facto Houthi authority that has all but won the civil war and a divided internationally recognized government, which is unable to take its seat in its own temporary capital.

State fragmentation in Yemen is a consequence of several events, the political, economic and social marginalization of multiple social groups specifically, and more generally, the country as a whole, by the former regime which has manifested into strong grievances. Furthermore, the failure to address the grievances post-2011 popular protests. Third, a mismanaged transition of government, and finally, the incoherent Arab Coalition intervention.

Although the patronage system created by Ali Abdullah Saleh managed to stabilize Yemen in many ways, it also favored the northern elite and tribesmen, which was the core reason for the uprising in 2011; this was followed by the Yemeni elites’ and the Gulf Cooperation Council’s (GCC) failure to address local grievances after the 2011 protests through the GCC initiative.

Yemen is also fragmented due to the failure to address local contexts in restructuring institutions following Saleh's ouster

The initiative called for peace at the expense of justice, eliminating all accountability for injustices of the former regime. This negligence to take local demands seriously is a constant in Yemeni politics, including current peace initiatives, which continue to ignore local contexts, whether historical or modern, and is the primary source of fragmentation.

Yemen is also fragmented due to the failure to address local contexts in restructuring institutions following Saleh's ouster, specifically, security sector reform. A superficial “Security Sector Reform” (SSR) was initiated by the interim government as part of the GCC initiative in the form of personnel transfers, renaming of militaries, and commanders without considering the consequences of ignoring the very roots of the tribe-dominated, patronage-based security sector structure built in under Saleh.

The result was a fragmented military that was not loyal to its new command. The military divisions were the crack that expanded to countrywide fragmentation. These divisions saw parts of the military remain loyal to the disposed president Ali Abdullah Saleh, which made the Saleh-Houthi coup d'état possible, leading to the subsequent civil war.

Moreover, the leftover military components were primarily under control of the Islah party – Saleh’s partners in crime, leading to the creation of an unpopular transitional government dominated by Islah components, which is a primary factor in the current fragmentation of Hadi government-controlled areas.

In the North, fragmentation was primarily a result of Saleh’s policies

Finally, the incoherent foreign intervention initiated by the Arab Coalition, which has reflected the interests of the coalition’s individuals’ members at the expense of the already weak Hadi government’s legitimacy, has cemented social fragmentation, furthered institutional fragmentation, and led to the dislodging of the Hadi government from its temporary capital in Aden.

In the North, fragmentation was primarily a result of Saleh’s policies. Despite being more inclusive than other countries in the region, these policies inevitably favored a minority, and with time, the gap of wealth and political power grew apparent in communities. The popular protest in the North was fueled by this inequality of wealth and opportunities brought about by a patronage system that favored the ruling elite. The second factor was the attempt to replace local Zaidi Islam with a state-sponsored Saudi Salafism.

In 1990, Saleh moved to support the corrupt political system he was building by promoting Salafism in an attempt to tie his government to religion – similar to Yemen’s GCC neighbors – Islam prohibits uprisings against the ruling elite absent a religious decree by recognized religious scholars which makes it attractive to uncontested rule. The then dominant form of Zaidi Islam permits uprising against unjust rule without conditions.

The Houthis were an armed political movement that identifies with Zaidi Islam, the heart of the Imamate dynasty, which ruled northern Yemen for almost 1,000 years. Amid the popular protests, the Houthis joined in to voice their discontent towards the regime. During the 1990s, in an attempt to move away from Zaidism, which not only threatened Saleh’s rule, but also that of Yemen’s Sunni neighbors, massive investment by Saleh under the auspices of Saudi Arabia was initiated to spread Salafism through religious schools, which were built in the heart of Zaidi territory around the town of Sa’ada.

The Houthis have managed to frame the coalition’s destructive bombing campaign as a “foreign aggression” on the country

The campaign was viewed as distorting the identity of the Zaidi population. Grievances towards the state’s sponsorship of this massive campaign to diminish Zaidism manifested over time, and even pre-Arab spring, an insurgency began that aimed to take control of Sa’ada. This Houthi insurgency fought to separate the area politically, economically and socially from the now Sunni-dominated state. The population of Sa’ada was mostly deprived of basic public services; education in particular was absent, partly to avoid Sunni influence on Sa’ada’s population.

From 2004 to 2010, the government waged six devastating wars against the Houthis, who had succeeded in forcefully assuming government functions, including control over security, judiciary, and tax collection. The wars led to more hardship for the impoverished people of Sa’ada and in combination with the attempt to suppress their identity, this led to even more grievances towards the state.

By 2014, through a marriage of convenience, the Houthis had managed to take control of the country in a coup d’état in partnership with their historical enemy, Ali Abdullah Saleh. They derailed the plan of a federal state that the people of Yemen had envisioned post popular protests of 2011.

Popular support for the Houthis following their takeover of Yemen is not ideological but can be mostly attributed to the successful continuation of the patronage system built by Saleh, even after his death in 2017. This situation has been evolving over the years, as the Houthis have managed to frame the coalition’s destructive bombing campaign as a “foreign aggression” on the country, thus turning a sizable share of the population into supporters of the group. After controlling densely populated areas equaling over 80 percent of Yemen's total population, the group cemented its grip on the state.

Social fragmentation in the North has been accelerated as a result of the new Houthi elites

Today, social fragmentation in the North has been accelerated as a result of the new Houthi elites. Ironically, similarly to how they were marginalized in the past, the de-facto authority has now initiated government-sanctioned ancestral discrimination as per their religious tradition. They bode that only Zaidi Sayyid descendants have the right to govern the country. Moreover, this is extended through taxation that exclusively benefits Zaidi Sayyid descendants and other forms of marginalization towards the population in areas under its control, such as indoctrination of discriminatory values that favor Zaidi Sayyid bloodlines and Zaidism through newly designed school curricula.

In the South, the local identity differs significantly from the North, partially because the South was a British protectorate following post-independence in 1967. Thus, parts of the South, such as the political capital Aden, do not have tribal components, moreover secular values among the population exist.

Grievances shared by the population in these areas are by far the most extreme in Yemen and result from the political marginalization of the South by the northern government post-establishment of the Greater Yemen in 1990, and subsequent economic and social marginalization after 1994; this area also experienced strong initiatives to promote Sunni Islam, instead of secular ideals that were widespread pre-unification.

The southern part of Yemen was an independent state (The People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen or PDRY) until unification with the North in 1990. After unification, the power-sharing agreement between the two states was undermined through an unbalanced electoral process that favored the densely populated North over the South. The system allowed two main, mostly northern, political parties, Saleh’s General People's Congress (GPC) and Al-Islah, to form a majority in parliament and government.

At the conclusion of the war in 1994, the central government in the North succeeded in holding the South by force

Together, the two parties controlled the new state, effectively reducing southern participation in decision-making to less than the agreed 50 percent. This led to a civil war that aimed to reinstate the former southern state. At the conclusion of the war in 1994, the central government in the North succeeded in holding the South by force, and southern governance was effectively handed over to the Sunni-based Islah party, which initiated a massive campaign to transform the existing secularism to a religious conservative society. Moreover, former southern leadership and public servants were removed from their posts, and the South (including resources, land, and assets) essentially became spoils of war for the northern elite.

By 2007, Al-Hirak Al-Janoubi was established in Aden. The umbrella movement brought together several groups that advocated for an end to the marginalization of southern governorates, some seeking complete independence, while others were seeking more autonomy from the central government. At that time, Al-Hirak aimed to reinstate civil and military servants cast aside following the 1994 war.

Amid the Saleh-Houthi incursion into Aden in early 2015, the Arab coalition’s military campaign began. This campaign mobilized the Saudi and Emirati air force, ground forces from the military loyal to Hadi, as well as informal components from the South. The most crucial component of this campaign was a combination of civilians and southern tribes brought together under informal militaries funded and trained by the UAE.

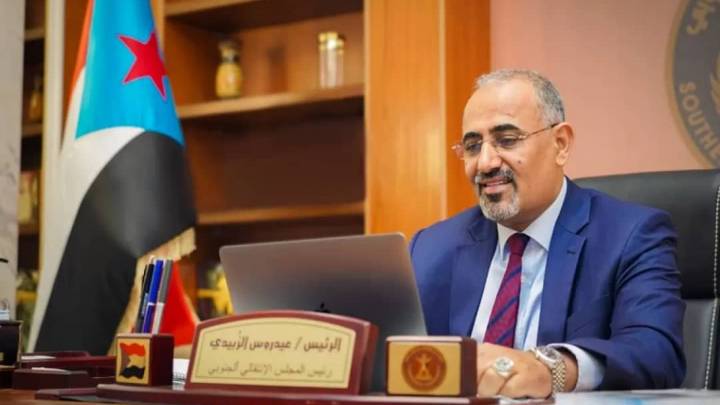

At this time, Al-Hirak together with others turned into a full-fledged armed movement – The Southern Movement. Later, following the expulsion of Saleh-Houthi forces from Aden, its components that had advocated for complete independence of the South, established the Southern Transitional Council (STC), which is now the de-facto authority in Aden.

The STC has successfully mobilized popular support for the reestablishment of the southern Yemeni state

Considering the traditional Emirati economic interest in Yemen’s southern coastal cities (especially Aden), the UAE likely funded the informal military components to guarantee a future ally in the South, given its skeptical view of the loyalty of the Hadi military and its political leadership. The campaign was successful in reclaiming the southern areas of Yemen. However, this campaign's informal military components continued to grow with Emirati support and eventually aligned with the de-facto government in Aden, the STC.

The STC has successfully mobilized popular support for the reestablishment of the southern Yemeni state and has all but eliminated the Hadi government’s presence in all major coastal cities in the South. Although these new informal actors may consider the UAE an ally, their core prerogative is the Southern cause, and they do not seem to answer, neither to the UAE-Saudi coalition, nor the Hadi government. While some would consider this authority and its military forces illegitimate, the STC now enjoys popular support in the South and is no longer informal but, in fact, moderately institutionalized.

In the east, Hadhramaut also defines a particular Yemeni identity, namely tribal components, being also part of the PDRY following independence from the UK in 1967. This area was a cash cow for the Saleh regime, namely through its abundant natural resources, but saw little development relative to the massive revenue the governorate generated.

This imposition of a largely extractive economic structure was the source of grievances in this area. In the National Dialogue Conference (NDC), particular emphasis on directing resources from Hadhramaut towards its development was voiced, and today 20 percent of local oil revenues are kept locally.

Hadramawt has managed to balance the STC and Hadi government control so far, but the outcome is likely to follow the Aden scenario

In the course of the civil war, a security vacuum emerged in Hadhramaut and gave rise to terrorist components that briefly established a local government but were later kicked out by the informal, UAE-backed Hadhrami elite forces and local Hadhrami tribes. Today, on the one hand, the Hadi government controls inland areas in the governorate and employs military forces that are widely unpopular because they mostly consist of Islah components.

On the other hand, the UAE-backed elite Hadhrami forces, governed by the STC, control coastal areas such as Mukalla and enjoy more local popularity, similar to the situation in Aden. The governor of Hadramawt has managed to balance the STC and Hadi government control so far, but the outcome is likely to follow the Aden scenario in the future given local calls for an independent state and the downward trajectory of the Hadi government’s legitimacy across the country.

Hodeidah, the capital city of the Tehama region, is considered Yemen’s primary port city. Locals in Hodeidah have also voiced the need for more autonomy from the central government in Sana’a since 2012. Like other areas in Yemen, local government was dominated by northerners. Historically, the population in Hodeidah has been suffering from marginalization, exclusion, and discrimination due to their unique social identity, and despite the region’s significant contribution to Yemen’s economy through its seaports and fertile land.

The elites from the North have exploited both the people and the land, and only little of the region’s resources have benefitted the local population which has always viewed themselves as ruled by outsiders from the rest of the country. This fact led to discontent and intermittent uprisings against the ruling elite during the Arab Spring. The Tehama Peaceful Movement eventually morphed into a full-fledged army, the Tehama Popular Resistance (TPR), that participated in the recapture of the southern part of Hodeidah from the Houthis.

Effectively on the ground, the former North and South states of Yemen came to exist, once again

Following the expulsion of Houthi-Saleh forces from Aden, another campaign was launched to liberate Hodeidah, composed of forces originating from the South, from Hodeidah itself, and an army made up of the Saleh loyalists’ remnants, headed by his nephew, Tareq Saleh.

Despite all being supported by the UAE, the only component with continued support after the campaign’s success is the “Guardians of the Republic” force headed by Tareq Saleh. This army is now, alone, considered a formal government military. Despite being locals, the TPR has been ignored by both the Hadi government and the Stockholm agreement of 2018.

This has accelerated fragmentation within the ranks of this force that is nominally loyal to the Hadi government. Today, the historical grievances against northerners have returned, as Saleh’s nephew dominates the governorate’s government-controlled areas, while the Houthis control the rest.

Effectively, the Yemeni state no longer exists. The Houthis control the northwest from the Saudi border to the city of Taiz in the southwest, with active frontlines running along the border of the formerly independent south. Saleh's nephew dominates Southwestern Yemen (Tehama). Yemen's south and southeast are now riddled with divides between the Hadi government and the STC, with all coastal areas in the South under STC control, which have declared self-rule.

Six years into the Yemeni civil war, the picture looks bleaker than ever. The Hadi government has become all but a lost cause and no longer enjoys legitimacy or popularity. While the warring parties and international community discuss peace initiatives that have yet to reflect historical or even modern local context, the situation on the ground is more fragmented and slowly continues into a downward spiral.

Mohamed Al-Iriani is a Fellow at the Yemen Policy Center (YPC).