The death of filmmaker Shady Habash makes author Wael Eskandar think of a friend who goes by the same first name - and of how the Egyptians deal with injustice and loss.

I never knew Shady Habash, not personally. He was not my friend. He was probably someone I would have otherwise never have heard of. Perhaps our paths may have crossed had I continued working on satirical projects with Shady Abu Zeid. But Shady Abu Zeid was arrested without reason, we suspect it was for one of his pranks and Shady Habash was arrested for a song. I myself was not part of neither this particular joke, nor that particular song, so I wasn’t arrested. I stopped pursuing other silly projects.

Maybe it would have been easier had I quit out of fear. Honestly, it would have been a better reason to stop, it would have made more sense. I stopped out of devastation. Shady Abu Zeid was someone who showed me the power of silliness to address serious issues. We had been working on such a collaboration just before he was arrested. It was not political. It was a song written to reflect a controversy. That is how he liked his work, provocative and meaningful rather than simply repetitive and predictable to garner applause.

Shady Abu Zeid is an Egyptian blogger and satirist who rose to fame with his viral videos interviewing people on the street asking them ridiculous questions and getting funny responses. On 25 January 2016 he released a video in which he handed out balloons made of inflated condoms to the security forces. The prank went viral much to the Ministry of Interior’s dismay. Two years later there was an early-morning knock at the door and Shady was detained without charges.

It was only then, in May 2018, when Shady Abu Zeid was arrested that I started hearing about another Shady, Shady Habash. Initially I was confused because, as it turns out, they were both thrown into Cairo’s Tora prison, but held in different cell blocks. Sometimes when their mutual friends relayed news to us it was difficult to tell which news applied to which Shady. Shady Habash died in prison. His cellmates called out to the guard to ask for medical attention before he died, but the guard did not open the cell door. That is not an exception, it is policy. I have struggled to find words to describe what happened. Simply describing it as deliberate negligence towards human life does not quite cut it.

Art is not a luxury rather it is essential in the fight against the ugliness of injustice.

Somehow the notion that they would have unlocked his cell to save him when his cellmates called out seems frankly ridiculous. They never cared about his life anyway. The only reason they did not murder him for the song he directed in the first place was possibly because it was inconvenient. They never cared that he was a creative young man whose freedom they took away without judge or jury. Shady Habash was arrested because someone was upset, not because he broke a law. They did not interrogate him, nor did they put him on trial. Pretrial detention was the verdict. Pretrial detention was the sentence. It was death by pretrial detention.

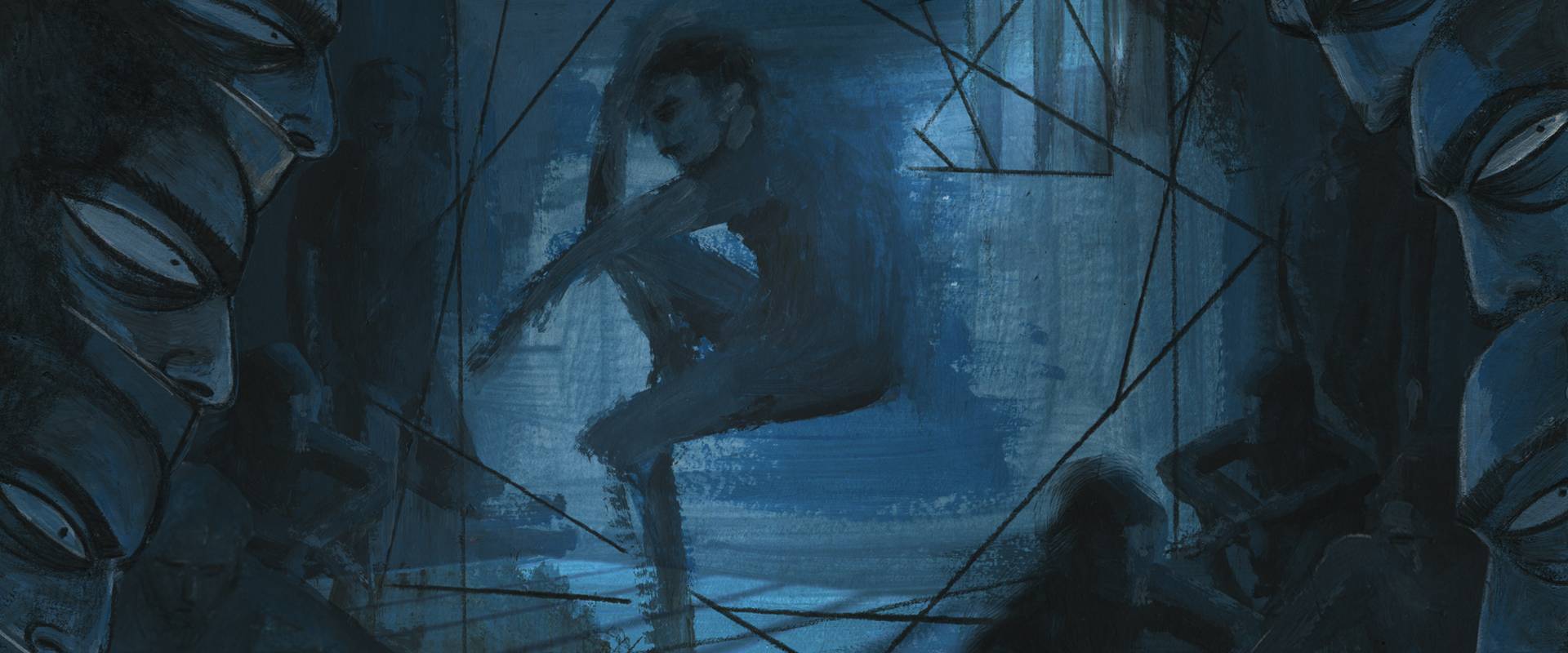

There is something extra heart-breaking when the most creative among us are stripped of their freedom. Their arrests are not only a personal tragedy but represent a direct attack on creativity, on art itself. It is a direct attack on that which keeps us alive. Art is not a luxury rather it is essential in the fight against the ugliness of injustice – the two are polar opposites.

This is why it was always painful to chance upon news of Shady Habash while following up on my friend Shady Abu Zeid. These two young people are among a different category of regime targets. They are not political activists like Mahienour el-Massry or Alaa Abd El Fattah and numerous others who hold political beliefs diametrically opposed to the regime’s authoritarianism. They are simply artists. Regardless scores of those who belong to these groups now languish in prisons across Egypt.

This is how we deal with tragedies these days; we know we cannot avoid them, and when they catch up with us, we pray they have not befallen those closest to us.

Shady Abu Zeid spent over two years in prison. To torture him and his family they ordered his release in February this year and just moments before he set foot outside, they fabricated a new case against him to keep him locked up. The charges, attempting to overthrow the regime from inside prison. I was devastated by news of Shady Habbash’s death. It was a feeling of utter loss, utter helplessness. But if I am honest, I was grateful we had never met before. I was grateful he was not someone who was close to me.

I was grateful it was not the Shady that I knew. Though it may seem particularly callous to those who knew him, I was grateful it was not the Shady I knew. Maybe they too would have wished that the Shady who died was not their Shady. This is how we deal with tragedies these days; we know we cannot avoid them, and when they catch up with us, we pray they have not befallen those closest to us.

The death of Shady Habash resembles that of Khaled Said. Both Shady and Khaled were young men with their lives ahead of them, both victims of Egypt’s security apparatus. The murder of Khaled Said in June 2010 at the hands of police in Alexandria was covered up by the state. His murder was a big factor leading up to the revolution which started in 2011, emblematised by the solidarity slogan, “We are all Khaled Said.”

We are all Shady Habash, the antithesis of being ‘all Khaled Said’.

We are all Shady Habash now. This is not some political grandstanding akin to what we did when we claimed: ‘We are all Khaled Said’. This is the transformation we brought on ourselves when we decided to stand up for the right of Khaled Said not to be murdered by the state with impunity. We can no longer be Khaled Said. Khaled’s death awakened a nation to stand in protest, to act and try and put an end to that sort of injustice. We chose to be Khaled Said of our own volition back then and there were many who stood up and fought for the many Khaled Saids that have died.

We can no longer be Khaled Said, that option is lost to us. Now we are all Shady Habash, meaning that nobody will protest on our behalf. We will slip away in silence and sadness. Censorship will mean news of our deaths will go unread. Our muted voices will not allow us to accuse the regime of murdering us. To point out their responsibility would be to condemn our loved ones and friends to the same fate. We are all Shady Habash, the antithesis of being ‘all Khaled Said’.

Following the murder of Khaled Said, despite being in bed with the Mubarak regime, the international community applied pressure in response to human rights abuses. As we morph into Shady Habash, our deaths receive no condolences from those international actors. Colonialist powers in fact have sponsored our transformation – powers whose mouths are full of platitudes and promises of democracy while their grubby hands readily exchange arms with the regime.

This moment in time is characterised by our helplessness. There is no one to lobby, simply nobody to reach out to. Whenever someone is arrested, we have one of two options. We can launch a media campaign to bring attention to their plight or remain silent. Neither work. Media campaigns no longer an effective means of applying pressure. Western countries who once responded to human rights violations are accomplices in Egypt’s crimes and will therefore not move a finger so as not to jeopardise their interests. Besides, media campaigns often anger the Egyptian authorities, making them far more stubborn, so any attempt to highlight to plight of those behind bars may instead end up hurting them.

While the world is caught up in the coronavirus pandemic, we continue to trudge through the pandemic of systemic injustice.

The alternative is to remain silent and seek regime connections to resolve the matter, particularly because there is often no legitimate reason for an arrest. Such approach does not anger the regime, but since no pressure is applied it does not have to budge an inch. “Lock them up and throw away the key” is the prevailing attitude. After all, France would not dream of jeopardising its arms deals with Egypt having become its largest supplier between 2013 and 2017. The murder of the PhD student Giulio Regeni showed that Italy does not really care about the lives of their own citizens, let alone Egyptians.

And then, there is Germany who wants to keep refugees from leaving North Africa and to see out the construction of Siemen’s power plant, all the while submarines set sail from Thyssenkrupp’s shipyards in Kiel bound for the Egyptian navy. The same could be said of Canada, Greece, the Netherlands, Spain, the UK and the USA to name just a few. The victims of human rights violations in Egypt have no real allies, but the perpetrators have all the allies in the world. This is what we have to live with. We are too small in the face of the world.

It is a struggle to keep going and find meaning. It is a struggle to write and rewrite these thoughts over and over again. I am torn between resisting saying the same things again and again in vain and the need to express these haunted thoughts once more. While the world is caught up in the coronavirus pandemic, we continue to trudge through the pandemic of systemic injustice.

Remembering and surviving, two opposing duties that become harder by time.

How do we keep going? How do we find resilience? What is the meaning of resilience in this context? Perhaps it is to keep taking the hits, blow after blow. The weight of their pain accumulates, and I walk around with the burden of these tragedies I have witnessed and the weight of seeing them for what they are. I am helpless by the day and I struggle as I seek to retain the anger inside me instead of succumbing to the feeling of utter defeat and despair. I do not want to lose that anger or to let go of the memory of these injustices despite my helplessness, because if I lose that, I lose my humanity. As my understanding of my limitations grows, I realise I am not as effective as I once was. I miss the days when I naively believed I could make some sort of difference, because it spurred me to action, even if that action was in vain.

As time relentlessly marches on, I am stuck by my growing insignificance. Even though it seems that I should unburden myself of what I have witnessed, it seems all the more imperative to hang on to it. What is there to hold on to other than integrity. It would be devastating both to be helpless and forego my integrity. I try to convince myself that clinging to the anger and the truth I have witnessed is worthwhile, though I can do nothing about it.

Witnessing injustice is a cursed privilege. But cursed privilege is knowing without having opportunities to act meaningfully and change things. My feeble act is remembering. It is not as simple as it sounds because I need to not break down, I need to survive. Remembering and surviving, two opposing duties that become harder by time.

Wael Eskander was born in 1980 and spent his childhood between Egypt and the Gulf States. He was politically active before the 2011 revolution in Egypt and in 2006 he founded his blog Notes from the Underground. As a freelance journalist, Eskandar's work has featured in Al-Ahram, Daily News Egypt, Jadaliyya and Mada Masr, among many others.