The Islamic State is hunting down Afghanistan's Shia - and the looming peace settlement between the government and the Taliban could worsen the situation. Is the country about to be split along religious fault lines?

Five men stand in the shade of a tree looking over at the sky-blue domes of the nearby mosque. Guns older than the young men themselves are slung over their shoulders. The wooden rifle butts are darkened with the sweat of clammy hands, scratched barrels tell of conflicts past. That morning the guards were checking bags and backpacks, opening car boots and asking questions. Now the strength of the sun and the call of the mullahs drive the faithful into the mosque, and the courtyard framed by a high stone wall remains empty. Only children continue to play. They have long since become accustomed to the presence of their armed protectors.

The Daimirdadiha Mosque is located in a western neighbourhood of the Afghan capital Kabul. Most members of this Shia community come from the adjacent Maidan Wardak province. Today, around 200 men have gathered on the house of worship’s first floor and are listening intently to the story of Zainab and the Battle of Karbala. Sobbing can be heard over the crackling of the sound system. Fingers weighed down with chunky lapis lazuli rings clutch prayer beads as tears steam unashamedly down the faces of those present. These Shia worshippers are reminded of the sacrifices made in their name as the Arbaeen tradition demands.

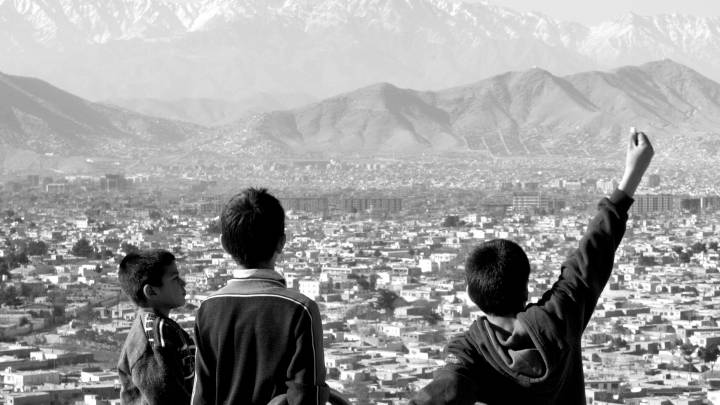

It is mid-October, the mourning month of Muharram has just come to an end. The Shia breathe a sigh. Despite their fears, their religious celebrations have passed without being attacked. When prayer ends, Haji Masjidi Nuri steps outside. Dust and smog have descended over a beige sea of houses, bathing Kabul in a golden light. The 76-year-old community leader’s eyes are dewy and reddened by tears, the wrinkles on his face hint at a long life beset by fresh worries. He glances at the young men armed with Kalashnikovs: “Up to five guards secure the mosque.”

Although the weapons are issued by the government, Haji Masjidi Nuri feels abandoned, forced to patrol his neighbourhood at night on tired old legs. “The government can’t even protect itself! Otherwise, old people like me wouldn’t be in charge of security.” He is right to be worried. The regional offshoot of the self-declared Islamic State, the Islamic State of Khorasan (ISKP) has orchestrated a bloody campaign against Afghanistan’s Shia ever since it emerged publicly in late 2014.

According to UN statistics, there were more than 50 attacks on Shia mosques and other community centres in 2016 and 2017. In these two years alone, 242 people were murdered, almost 500 were injured. As elsewhere in Afghanistan, this form of violence is on the rise. In 2018 alone, 223 people were killed in anti-Shia attacks, almost 550 were injured. Knives, assault rifles, explosive vests and complex attacks have almost doubled the numbers of victims.

The ISKP, which is now mainly based in the eastern Afghan province of Nangarhar, has claimed responsibility for most of these attacks. After initial military successes, the group quickly came under pressure from the Afghan army and its US allies, as well as the Taliban, who are officially hostile to the ISKP. Despite this, the UN estimates that the group boasts as many as 4,000 fighters.

Fighters, weapons, and money are not the only things that they have imported from the Middle East. A particular worldview has also made the journey. “There’re a lot of problems in Afghanistan. War has raged here for years.” But Afghan analyst Hekmatullah Azamy is convinced: “One thing that has never existed here is sectarianism. That changed with the emergence of the Islamic State.” Azamy is a researcher at the Centre for Conflict and Peace Studies, a Kabul-based think tank close to former President Hamid Karzai.

Azamy warns against the emergence of splits in Afghan society along religious fault lines. His fear is that the Afghan multi-ethnic state with its weak central government could become a tinderbox for would-be spiritual arsonists – and religion a predetermined breaking point: “If we don’t unite to fight this ideology, we’ll end up sharing the same fate as Syria or Iraq.”

Afghanistan is home to many ethnic groups, often separated by mile-high mountain ranges such as the Hindu Kush and Koh-i-Baba. Although the government cannot provide exact figures, the predominantly Sunni Pashtuns probably comprise up to half of the 35 million Afghans. Ethnic Tajiks make up another quarter, while Uzbeks and Hazara each account for ten percent of the population.

The Hazara live mainly in the provinces of Bamiyan and Daykundi in central Afghanistan, speak a form of Dari which is a local variety of Persian, and consider themselves to be descendants of the Mongol conqueror Genghis Khan. Although there are also Shia Pashtuns and Twelver communities of the Sevener Shia Ismailites, Hazara and Shia Islam are used synonymously by many Afghans.

“We met at the office in 2014, but for over a year neither of us found the courage to speak to the other,” recalled Nikbakht Husaini*. The young Hazara was working in a travel agency at the time and it was their mutual boss who matched the 26-year-old and his work colleague. Since then the two have been fighting for a common future together, because the Sunni family of the Tajik woman rejects Husaini. “What’s the problem?” Husaini asked her father. “I am Shia, you are Sunni. I accept that. But we’re all Muslims. We have the same God and the same Prophet.” It took him nine months to first get her father on his side and then win over her mother.

The two families were in the middle of preparing for the wedding of the young couple when disaster struck. “In 2017 my brother was killed in a bomb attack in a mosque, his wife and two children were injured,” Husaini whispers. His youngest nephew lost his right eye in the explosion when a piece of shrapnel entered the child’s skull. The doctors are at a loss and do not dare to operate for fear of further brain damage. Husaini put his own plans on hold to take care of his family.

Today, two years on, Husaini and his girlfriend are forging new wedding plans. But now his girlfriend’s little brother has expressed concerns. Husaini believes that it was her uncle, a conservative preacher, who put him up to it. “At first, I didn’t care that I was Shia and she was Sunni. I was in love and thought nothing could stop us,” he remembers. “True Muslims and educated democrats shouldn’t be guided by prejudice.”

That is wishful thinking, according to analyst Hekmatullah Azamy. He has observed growing sectarian prejudices among large parts of the population. “Many Afghans are increasingly adopting extremist Salafi ideas. I’ve seen many such debates. Suddenly Shia are declared infidels. This worries me. It threatens social cohesion.” Azamy’s Centre for Conflict and Peace Studies claims to have discovered that this interpretation of Islam is being spread in particular by Saudi-financed Quran schools and imams who have trained abroad. Another factor is that many Afghans now get their information from the internet. “Information used to be hard to come by,” explains Azamy: “But nowadays, people go online, and much of what they read about Shia and Sunnis comes from Salafi sources.”

It is not easy to find the Shia cemetery. Here on a hill, on whose beige flank a spur of Kabul nestles. A strong wind sweeps down from the mountains, tearing the black, red, and green flags that decorate the rows of graves. The big city seems peaceful from here. The smog is somewhat bearable. Kabul’s soundtrack can be heard – a medley of spluttering engines and whirring rotors of US transport helicopters. Dreams are laid to rest on this cemetery. Like those of Behroz Sharif, who had just been admitted to a Chinese studies course shortly before his murder. Beside the many gravestones, a mother lies curled up in a colourful woollen blanket on her son’s final resting place. A father squats silently alongside, gazing at his wife and son, the cigarette in his hand has long been reduced to ash.

“Whoever has a single ounce of humanity inside them must understand when they see these graves, why we Hazara reject the present system,” says Ahmad Behzad. His dark eyes shimmer faintly when he remembers 23 July 2016. It was a day when Behzad – a political activist or an activist politician, it is not possible to say exactly – was in his element. As a prominent figure in the Junbesh-i Roshanai or Enlightenment Movement, he lead thousands of Shia through Kabul. They were demonstrating against the decision not to lay a planned power line that should have brought electricity and development to the home provinces of Hazara. In the middle of this protest march, two suicide bombers detonated their explosive vests. Eighty people died, 230 others were injured, some of them seriously. Behzad survived, his dead comrades-in-arms are buried on the hill at the edge of the city.

With his accurately trimmed, greyish beard, casual button-down shirt and tailored jacket, the 45-year-old Behzad could easily be mistaken for an investment fund manager in the City of London. It is his voice that betrays the politician, how he weighs the words before he releases them at a pleasant temperature into the room. “The government claims to be addressing our concerns. But it’s not true.” Behzad was a member of the Wolesi Jirga, the Afghan lower house, and therefore could actually be seen as part of a political success story. It was the government under President Hamid Karzai, that passed a constitution early on that guaranteed equal rights for all ethnic groups in the country.

Hazara such as Behzad therefore get into political offices, become part of the government and are sometimes even overrepresented in parliament. For Behzad, it is these political successes in the new Afghanistan that have made the Hazara enemies of the Pashtun establishment and targets of attacks. Life in Afghanistan is dangerous. Even more dangerous for exposed politicians. A mixture of fear, death threats and experienced losses fuel a heavy air of paranoia.

Who are the Hazara?

The Hazara people live mainly in an area in central Afghanistan, the so-called Hazarajat, around the districts of Bamyan, Daykundi and Ghor. The Hazara speak a form of Persian, Hazaragi, which is closely related to the Dari spoken in Afghanistan. At present, the Hazara are said to comprise roughly 10% of the Afghan population of 35 million.

These figures are, however, based on approximations and should therefore be treated with caution. Although it was decided as part of the 2001 Bonn Agreement after the fall of the Taliban that a census should be held, it has been repeatedly postponed in the face of immense logistical obstacles, political challenges and security concerns.

The Hazara are considered ‘East Asian’ in appearance by other Afghans. The origin of the Hazara (from hazar, Persian for thousand) is commonly attributed to a thousand men of Genghis Khan’s army, who are said to have settled in Afghanistan in the 13th century on their way westwards.

However, some among the Hazara reject this interpretation and instead refer their origin to the time of Caliph Ali in the mid-7th Century. During the Safavid period some of those living in the Hazarajat probably also converted to Twelver Shiism. In Afghan society, which has been mostly dominated by Sunni Pashtuns, the Hazara have traditionally occupied a low rung of the social hierarchy. Poverty, hunger, lack of prospects and oppression drove many Hazara to leave the Hazarajat for Kabul and the northern city of Mazar-i-Sharif as well as for the neighbouring Iran and Pakistan.

By the 1890s, a large Hazara community had settled in the Pakistani city of Quetta in the south-western province of Balochistan, having fled brutal persecution under the regime of Emir Abdur Rahman Khan. Strangely enough, no Hazara can traditionally be found living in the Pakistani region of the same name around the city of Abbottabad.

After a phase of relative calm, the Hazara’s situation worsened once again when in 1989 the Afghan civil war broke out. Under Taliban rule, thousands of civilians were killed in numerous massacres perpetrated in the Hazarajat, and much of the region was destroyed, including the famous Buddha status of Bamiyan.

Even in exile in Pakistan, the Hazara have been increasingly targeted by Sunni extremists, especially after 2001. The Afghan constitution of 2004 states that the Hazara and all other ethnic groups are of equal legal status. By Leo Wigger

Behzad lives in one of Kabul’s oldest districts, the exact location of which he likes to remain secret. His property lies at the end of a narrow access road with no possibility of escape. The high clay walls obscure any view, and hooded gunmen check bags, backpacks and intentions. He mentions the intrigues that parts of the government may be forging against the Hazara. He talks about alliances that politicians and the Taliban are supposedly forming, and he claims that the omnipotent National Directorate of Security played a role in the devastating attack on the Enlightenment Movement.

Lotfullah Najafzada is not alone among political observers who consider such an escalation of the debate to be dangerous populism. The 31-year-old Hazara is the director of the television station TOLOnews and one of Afghanistan’s most prominent journalists: “If you want to play the ethnic card, you start to set the victims against each other. I think it’s unhealthy.” Najafzada himself has lost colleagues from the newsroom in an anti-Shia motivated attack by the ISKP and believes: “We should regard all people as Afghans. Then any attempt at division will be in vain.”

But violence in Afghanistan has repeatedly taken ethnic and religious turns. The persecution and discrimination of the Hazara culminated in the late 19th century when the Pashtun ruler of the country, Abdul Rahman Khan, dubbed the ‘Iron Emir’, brutally suppressed several of their revolts in the 1890s. The surviving Hazara women and children were sold as slaves in the markets of Kabul and Kandahar.

Hazara also suffered under subsequent rulers, but it was the rise of the Taliban amid the chaos of the civil war that followed the Soviet occupation that ushered in a new era of particularly relentless persecution. A notable example was the Taliban commander Mulla Manon Niazi who ordered the targeted execution of members of religious minorities after storming Mazar-i-Sharif on 8 August 1998. Human Rights Watch estimates that thousands died. After the fall of the Taliban, UN forensic experts discovered mass graves in Bamiyan, where up to 15,000 Hazara had been massacred and buried.

A backyard at the end of a short turnoff from the bazaar street in the centre of Bamiyan. The ground is sandy, not asphalted. Oil, grease and petrol cause streaks between the half a dozen sheds that are set up here. Engines howl, a wrecked car is worked on with a sledgehammer, young mechanics on scooters curve back and forth between the huts.

Mirza Hussain works here. His coarsely knitted dark blue cap sits on his head at a jaunty angle, barely covering his receding hairline. He extends a hand coarsened by the experiences of the work it has performed. Hussain was imprisoned for four years by the Taliban after they overran Bamiyan, the heart of the Hazarajat.

Hussain has bitter memories, as he is one of the men who was forced by the Taliban, shortly before their fall in 2001, to destroy the world-famous Buddha statues of Bamiyan. “They said that because our ancestors carved these statues from the stone, it was our duty to destroy the Buddhas with our own hands. When I heard that we were to blow up the statues, I first became angry and then lost all hope. I knew that one day I would regret this act. It broke my heart.” Like eye sockets, the empty niches stare blindly into the valley today, a stone monument to barbarism and at the same time a warning sign for the Hazara in view of the return of their tormentors.

Today, the resurgent Taliban face the question of how to deal with the military and ideological competition from the Islamic State of Khorasan. The official line is clear. The ISKP is to be fought, anecdotal reports of cooperation in the fight against the Afghan army are denied by Taliban spokepeople.

Analyst Hekmatullah Azamy, however, warns against viewing the Taliban as a monolithic block. In fact, Salafi and anti-Shia elements have always been present in the movement, even more so since their return from exile in Pakistan some 15 years ago. Azamy believes that Salafi currents have continued to grow ever since.

This process has been aided by prominent figures such as Abdul Rauf Khadim. A member of the Taliban whom the Americans released from Guantanamo Bay in 2007 and repatriated to Afghanistan. “He came back, and together with the government we looked for ways to integrate him into Afghan society,” Azamy recalls: “When we called a Shia tailor to dress him first, Khadim began to question him. Are you praying? How do you pray? Why are your ankles covered?” Not long after his release, Khadim re-joined the Taliban and began harassing Shia in his sphere of influence, prohibiting them from visiting certain shrines. Then he changed sides and quickly rose to deputy commander of the ISKP.

Khadim was not alone in making the switch. In 2015, Taliban commanders in a total of three provinces – Helmand, Farah and Logar – joined the ISKP. “The Taliban leadership has not publicly condemned the anti-Shia elements for fear of further splitting the movement,” Azamy believes.

In view of this dynamic, observers are particularly concerned about the peace negotiations between the USA and the Taliban. The Taliban’s objective, which is limited to Afghanistan, appears to some of its most devout followers as a religiously veiled, but ultimately nationalist project rather than the global project of establishing an Islamic State. The participation of the Taliban in government with Washington’s blessing could be easily exploited by the ISKP, and the Salafists could benefit if the Taliban were to split following a peace treaty with the government.

This presents Afghanistan’s Shia communities with a threatening scenario. Although such an influx of former Taliban fighters would make the ISKP even more of a target for both Taliban and government forces, the group has shown astonishing resilience in the face of severe setbacks in recent years. Thanks to its geographical location and relative inaccessibility, eastern Afghanistan is already regarded by the IS as an ideal refuge. All the more so since its state-building efforts in Syria and Iraq have come to a halt for the time being. The deal between the Trump government and the Taliban might play into the hands of the ISKP, and obliterate Iran’s strategic calculations.

Tehran has so far backed the Sunni Taliban in their fight against US troops. Azamy is not alone in thinking: “If the Taliban make peace with the Afghan government and the US and, as a result, dissatisfied jihadists join the ISKP, the ties between the Taliban and Iran would be severed.”

Tehran could then be tempted to adopt a different strategy and attempt to redeploy Shia militias who were already in the service of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards in Syria. Estimates vary regarding the numbers of those fighting in the so-called Fatemiyoun Brigades – somewhere between 5,000 and 12,000. It has been mainly young Hazara men who have signed up, lured by money and the prospect of an Iranian residence permit, only to perish by the hundreds on the frontlines of Syria and Iraq.

What is certain is that the fallout of the Syrian conflict has already reached Afghanistan. There is evidence of IS fighters who have left the Middle East for the country, as well as documented returnees from the ranks of the battle-hardened Fatemiyoun Brigades. According to security sources in Kabul, there are no indications that the militias would organise after their return, but individual fighters have been integrated into units of the paramilitary Local Afghan Police under the Ministry of the Interior.

If that were true, they would now be part of a security apparatus that many Hazara believe is either incapable or unwilling to protect them from attacks of jihadist groups. And so, this year Hazara men will once again take up arms to protect the mosques at the heart of their communities. Additional reporting by Sultan Faizy.

* Name has been changed to provide anonymity.