50 years ago, Muammar Gaddafi expelled 20,000 Italian settlers from Libya. Today they could build new bridges, once they clarify their colonial past.

Even 50 years after his expulsion Giovanni Spinelli surrounds himself with his old homeland. The 89 year-old has put together colour photos of important colonial buildings of Tripoli to make a collage: Banco di Roma, Cathedral Santa Maria degli Angeli, and the Fountain of the Gazelle with it’s light sandstone and Roman-imperial style with oriental elements. All show the splendour of the colony that Spinelli may never get to see in person again, because much is destroyed or falling apart in the Libyan capital, and Tripoli is a city at war.

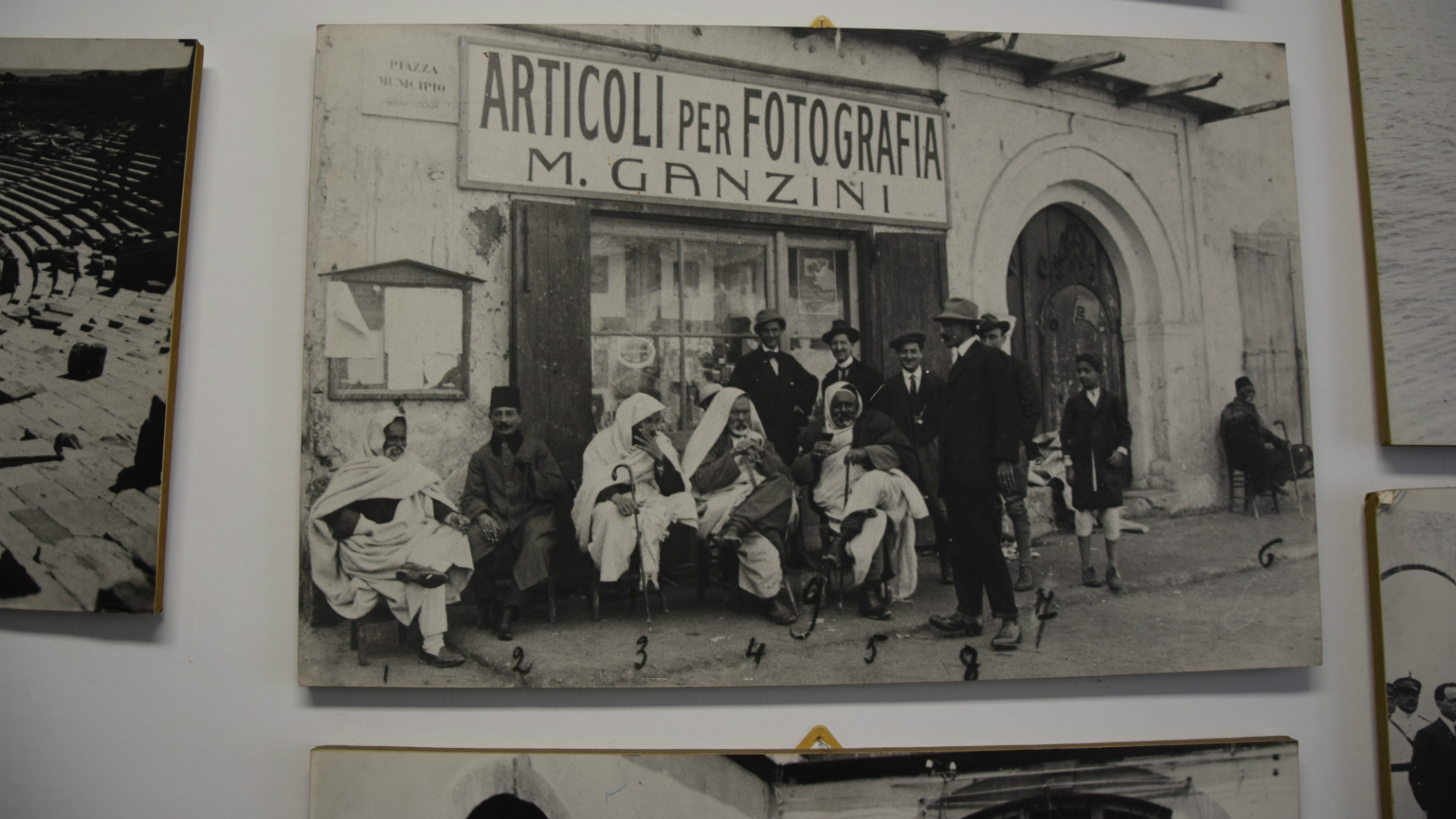

Giovanni Spinelli sits at his desk in the basement of the pharmacy which helped him start a new profession in 1970 after the eviction from Libya. It is located in Rome’s Trastevere neighbourhood. From the top floor the voices of his son Maurizio, who inherited the pharmacy, and other employees can be heard, along with the beeping of the cashier. In front of Spinelli lies his autobiography: “Farmacista per caso“. ”Pharmacist by chance“ is the title. Before the eviction Spinelli had been the owner of a profitable photography store in Tripoli. He had five employees and excellent relations with the important suppliers in Italy. He says: “I was on my way to becoming rich.”

Spinelli talks in a friendly and open way, in very decent English which he picked up as a young man working for the British Army and for US company Mobil Oil as an accountant. After the putsch of the Free Officers in 1969 their leader Muammar Gaddafi confiscated the funds of the 20,000 remaining Italian settlers and expelled them from the country. “I had a friend at my bank, this way I got at least some money out before it could be confiscated”, recalls Giovanni Spinelli.

Born in the southern Italian port town of Bari, Spinelli first came to Libya as an eight year-old. His father was one of thousands of peasants who were shipped in in order to cultivate the so-called Quarta Sponda (Fourth Shore) of the Fascist Italian Empire. The retired pharmacist still remembers the numbers of newly planted olive trees, the pioneer work of the Italians. “When I came back for the first time,” Spinelli recalls a delegation trip in 2004 (Berlusconi had just visited Gaddafi in his hometown of Sirte), “I was puzzled by the fact that the Libyans had not even cut the trees in the meantime. They did not have to work for their income, Gaddafi was handing out money for free.”

Spinelli does not sound bitter, he does not loathe the Arabs; on the contrary, he hails the happy coexistence of the three religious communities (until the Jews had to flee after the Six Day War in 1967) and what he probably regards as a well-working symbiosis of cultures. He refers to the time in between the Second World War and Gaddafi’s power grab, first under Allied administration and then under the Senussi King Idris, after the Fascist capitulation in 1943. “Indeed, the first Italians behaved like little Nazis”, Spinelli remarks about the earlier days, but he is quick to point out: “Italy did bad things like all European colonial powers.”

In Libya Italy committed a genocide. During the reconquest of Cyrenaica, cynically called “Pacificazione“, Mussolini’s men set up concentration camps, and they bombed and gassed villages from the air. Libya’s population was decimated from 1.4 million in 1907 to 825,000 in 1933. Many orphans were sent to Italian “re-education” camps and the social structure, economic make-up, and religious framework of Cyrenaica were devastated. The scholar Ingrid Powell states that “Italy’s thirty-two- year domination (1911–43) over Libya was perhaps the most severe experienced by any Arab country in modern times”.

Gaddafi utilized the traumatic recollections of Arab Libyans and he profited from the widespread longing of many young Libyans for something new. They cheered the proclamation of the republic. In his book “The Return” Libyan-British author Hisham Matar describes the first reaction of his father Jaballah Matar (he later became a major opposition figure who was abducted, jailed, and later killed by Gaddafi) who heard of the putsch during a visit to London: “When he entered the embassy and learned of the coup he jumped on the reception table to take down the picture of the monarch who he had served and admired.”

Libyan engineer Hassan Gritli recalls the same mood: “We wanted change, without knowing what it actually meant.” Gritli was 20 years old in 1969. His support for the coup diminished when the Italians were evicted. “They just chased off our neighbours, our good friends.” It felt like taking out a part of himself. “I am culturally an Italian”, says Gritli during the interview in the rooms of the Associazione Italiani Rimpatriati dalla Libya (AIRL). The organisation of the evicted Italians occupies three rooms in a yellow coloured city palace building north of Roma’s Termini Station. Gritli is closely connected with AIRL as he organizes sports events to bring together young Italians and Libyans. “Italy could play a big role in Libya”, he believes, “and the expelled Italians would serve the country very well, because they still feel like Libyans.”

Hassan Gritli went to an Italian school in Tripoli, has been married to an Italian since 1992, and he commutes between Rome and Tripoli (“Via Tunis and then by car, it takes eight hours. There used to be daily direct flights, one and a half hours only”, he sighs). His appearance wearing light blue trousers and a white polo shirt seems a lot more Italian than Arabic. “People today know that they had good times with the Italians”, Gritli says and points to a portrait of star singer Herbert Pagani, a Tripoli-born Italian Jew, which hangs alongside old Italian language posters and black and white photographs from Libya.

The AIRL organizes events for its members, it publishes the magazine “Italiani di Libia” quarterly and it advocates financial compensation. The now 80 year-old lawyer Giovanna Ortu is the president of the organisation. Her father came to Libya as a settler back in the 1910s. The year 1969 shaped Ortu’s life: She turned 30 years old, gave birth to her daughter Antonella and lost all of her belongings through confiscation. “Also there was the moon landing”, she says.

When Gaddafi confiscated the Italians’ possessions (estimated to be worth some three billion Euros today) the Italian government chose not to intervene. The interests of 20,000 Italians were weighed against those of the other 60 million Italians who profited from the dealings of national giants like Fiat or ENI. These companies could keep operating in the lucrative Libyan commodity market and the Libyans kept on investing in Italy. “When I saw this injustice I knew I had to do something”, Giovanna Ortu describes her motivation. Until 2008 some 150 million Euros were paid out to the former settlers, plus another 180 million Euros after Berlusconi and Gaddafi signed the 2008 friendship agreement. In total the expellees received only about a tenth of their assets back. This October AIRL plans to sue the Italian state for the rest.

When Berlusconi and Gaddafi signed the friendship agreement in 2008 this included a large compensation package for the damage inflicted by Italy for the crimes committed during the the liberal and fascist colonial eras. Some five billion Euros were supposed to be paid out to Libya in the form of major infrastructure projects, such as a highway along the coastline. Libya in turn agreed to stop migrant boats from embarking for Europe and Italy. Prime minister Berlusconi remarked: “Signing this treaty of friendship, partnership, and cooperation has a historical significance and it definitely fixes the colonial past.” Berlusconi thus tried to postulate an end to the discussions about the dark colonial past. Tempi passati– an approach echoing the sentiments of the former settlers. In conversations with them, all seem to make a sharp distinction: between the early colonial days (Ortu says apologetically: “We didn’t take the land from the Libyans, we took it from the Ottomans.”), the Fascist rule, and their own life time in Libya after 1943.

Professor Nicola Labanca of the University of Siena is an expert on Libya and Italy’s colonial past. In an interview with Zenith, he points out that in his country, the Italy colonial memory has never been de-colonialized, in contrast for instance to countries such as France and the United Kingdom where the political left championed this topic. The end of Italian rule with the capitulation of 1943 came too suddenly. “Italian Libya vanished for Italians like a dream, a dream that lingered, but of which there could be no precise knowledge or understanding”, says Labanca. “The sentiments of the expellees are not the problem here, the problem rather is that many Italians could share these feelings today.”

Especially now that Libya is caught in chaos and civil war, the colonial past moves out of focus. Old injustice and suffering are obscured by new injustice and suffering. But if someday Italy – and the Italians of Libya – want to take up an important role in post-conflict Libya, as honest brokers and trade partners, they must confront their own colonial past. Before opportunity comes responsibility. Labanca also refers to a partial responsibility for the unregulated migration of recent years from Libya.

Italy, however, has recently been moving into the opposite direction. Foreign minister Enzo Moavero Milanesi,in a visit to Tripoli last year, announced the revival of the 2008 cooperation treaty and vowed to reengage in jointly fighting illegal migration, but Matteo Salvini, Italy’s former far-right minister of the interior, has continuously followed a radical anti-migrant approach which postulates isolationism and ignores Italian responsibility.

Sitting at his desk Giovanni Spinelli sorts through old photographs from Tripoli. One of them shows the city’s promenade. “This was once one of the most beautiful lungomares in all of the Medieterranean, but under Gaddafi they filled all the land in”, Spinelli shakes his head and adds: “History is history, one cannot change it.”