The dead do not sleep: A journey through a country in which only one thought is stronger than the belief that no genocide took place – the fear that it actually did.

“You won't find anything now,” the Armenian researcher says in her office in Berlin. “Turkey has ensured that everything that remained from the Armenians after 1915 has since been destroyed.”

This prophecy, at least, turned out to be untrue. Turkey is full of Armenian remnants. Most are to be found outside the cities and normal routes: in tiny villages, on remote mountaintops, hidden in houses and backyards. More than anything, however, the Armenians – thousands and thousands of them – are in the heads of the Turkish people. It may sounds a bit irreverent to speak about the victims of mass murder in this way, but it is true: the dead of 1915 still haunt the country.

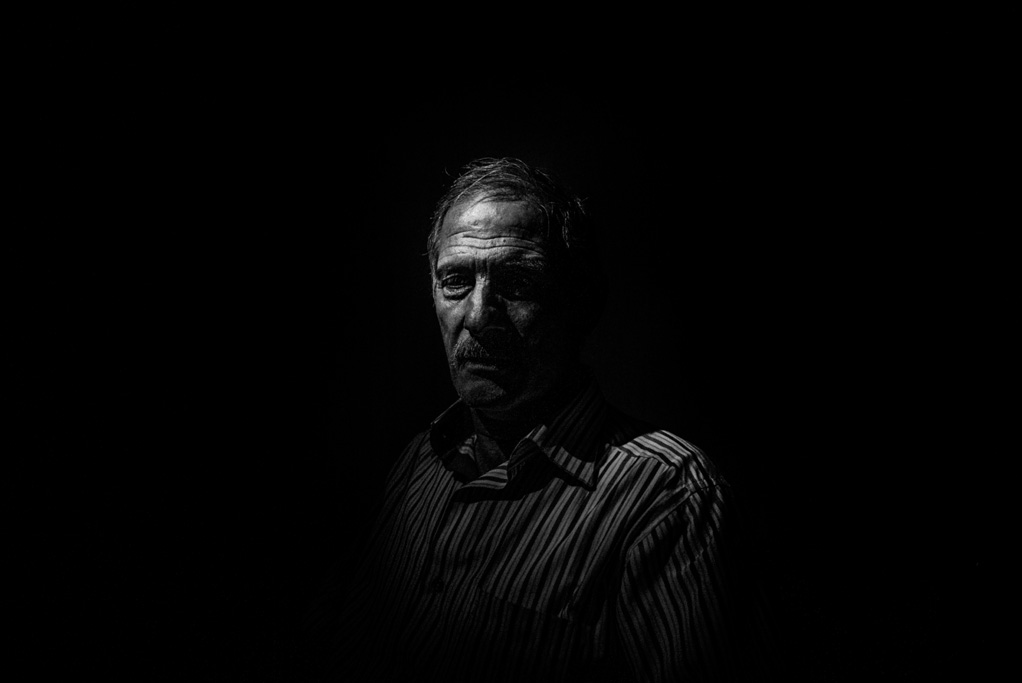

At a gravel quarry somewhere on the eastern edge of Turkey, a couple of workers take a quick break in the midday heat. Pieces of meat are being roasted on a knee-high grill and passed around with onion and bread. “We often find remains of houses here,” says Bülent. “And of people.” An Armenian village once stood on this spot, he says – back then, many Armenians lived around the Digor river, “together with us”. And then what happened? Did your ancestors kill the Armenians? “Yes, that is definitely possible,” answers Erkan, another worker. “We don't deny that. Anyway, we Kurds lived around here.”

The majority want to make quite clear that their own parents or grandparents were on the side of those who opposed the murders.The relationship that Bülent, Erkan and their colleagues have to the delicate topic is a different one: for Kurds, showing solidarity with the murdered Armenians – or at least not denying the major role of their own people in the genocide – is also an indirect form of revenge for the fact that they have also been under the heel of Turkish nationalism for decades. What catches attention, of course, is the discrepancy between a collective admission of guilt and the more familiar ‘clean slates’: the majority want to make quite clear that their own parents or grandparents were on the side of those who opposed the murders. If all the stories from Kurdish grandfathers that tell of selflessly protecting and hiding their Armenian neighbours were true, Anatolia would have been full of guardian angels.

A few kilometres away from the quarry, in an intoxicatingly beautiful river valley, lie the ruins of a tenth-century Armenian monastery, Beşkilise – ‘Five Churches’. Judging by old photos, it was quite imposing. It is a lovely, uninhabited area where tarragon and sumac grow by the roadside. “When I was young, three of the five churches were still standing,” remembers Kazim, a man from a Kurdish – previously Armenian – village a couple of kilometres further east. Today, only one still remains, atop a spectacular rocky outcrop. The others were blown up by the Turkish military sometime between 1920 and 1960.

In many cases, the state participates actively or passively – through inaction – in the slow disappearance of what remains of the Armenians who once lived here. The protection of Armenian cultural heritage is made difficult by the fact that treasure hunters are always out and about. They are victims of a greed – possibly deliberately cultivated – that has never lost its enticing power. “Do you have any idea where the Armenians' gold is hidden?” people ask, often at the most inopportune moment. All across the country, the remains of churches and cemeteries are riddled with holes.

The obsession with the idea that the supposedly rich Armenians buried huge amounts of gold nationwide as they fled or were deported – which may in some cases even have a grain of truth to it – is a useful accomplice in the project to eradicate not just a people but also any of their remaining traces. This is the second phase of a genocide. The third phase consists of extinguishing the memory of these people and their brutal murder; thought and speech about the genocide are labelled an invention or campaign and replaced by another narrative: “They attacked us”; “Back then, everyone killed everybody anyway.” Or, in the softened variant presented by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in his speech on 24 April, 2014: all ethnic groups suffered during World War I, and they must all be remembered, “without distinguishing between religion and ethnic origin”.

It is a murderous discourse, because it constitutes nothing less than the continuation of a genocidal politics, one in which Turkey has systematically engaged for a hundred years through a great deal of propaganda. Not without success: in some standard works of western Middle East research, the authors tiptoe around the subject of the Armenian genocide as soon as it comes up.

But Turkey is fighting a battle it cannot win. Too many demons are on the loose, and more and more are emerging. Some people are even finding the demons in themselves. Not because they discover a personal involvement in the history of the perpetrators – no, because they discover they belong to the side of the victims.

In the Family

Being Armenian in the young Turkish republic was nothing to be proud of.In Van, in Diyarbakır, in Muş – all across Anatolia one meets people who have found out there were Armenians in their family. Most were parents or grandparents who survived the genocide as children because they were rescued – or from another point of view, stolen – by Turks or Kurds. During the deportations, countless children were torn from their families; others wandered around in the villages and forests and eventually found a home with a new family. In the majority of cases it was girls and women that survived in this way. They were adopted, married and provided with a new, Muslim identity.

The emergent Turkish state knew about all of this. The Muslim Armenians, as they are called in Turkey, stayed silent, however, out of fear, out of guilt towards the relatives who hadn't survived, or out of shame – being Armenian in the young Turkish republic was nothing to be proud of.

The village of Çüngüş is high in the Anatolian mountains, around 100 kilometres from Diyarbakır. After a severe outbreak of winter – the heaviest for over 50 years, people say – all the streets are covered in snow, and forward movement in the steep alleyways is slippery and laborious. Two enormous church ruins are a reminder that this village also has a history. Thousands of Armenians from the area were killed. The majority were thrown in a river, the Dudan, which disappears thunderously into a crevice further down in the valley – an underground waterfall, impossible to survive.

Asiya, her daughter and her son-in-law huddle around the oven in the living room of their small house at the edge of Çüngüş. The smell of burning wood fills the room. Cautiously, Asiya straightens the cloth over her white hair. She is either 98 or 99, it can't be said for sure. Moreover, she is hard of hearing and can no longer walk very well. But she has the sense of humour of many of the old people here. To the question of how she is doing, she answers: “How do you expect I am? I sit here the whole day and don't hear anything.”

Asiya’s mother, as much as is known, was called Safiye – Sophia. At a deportation march during the genocide, she was taken by a Turkish soldier who wanted to marry the pretty Armenian girl. She must have been 12 or 13 years old. At some point thereafter Asiya was born, and her father, the soldier, died six months later. Asiya herself was married to a Kurdish shepherd at the age of 11. “I couldn't cook, I couldn't do anything at all,” she remembers. “So my husband always had to get food from elsewhere.”

Asiya, the almost 100-year-old whose mother was Armenian and whose father probably killed Armenians – who is she? The question of whether she is Armenian seems to make her uncomfortable; she glumly shakes her head. She beats energetically against her chest and says: “I pray five times a day.” After a short silence, she then tells of remembering how the neighbours would always say to her mother that she should dress her child as a Muslim, not as an Armenian. Her mother herself never spoke about the subject: “Everything that I know about her history I learnt later from others in the village.”

The few remaining survivors of 1915 will soon be dead, and the last ruins will eventually disappear.The genocide wiped out an entire generation. But many of their descendants have to fight with this legacy, until some of them are no longer certain of their own identity. Some Muslim Armenians hide their ancestry, some are ashamed of it, while others now profess to be proud. For still others it is no longer important, at least on the surface.

The few remaining survivors of 1915 will soon be dead, and the last ruins will eventually disappear. But as long as the country does not confront its own past, it will never find peace.

This article was first published in the 1/2015 edition of zenith

Research by Christian Meier and Andy Spyra was supported by the Border Crossers grant from the Robert Bosch Foundation.