While Arab youth join the labour markets in growing numbers, political leaders in many Arab countries seem unable to direct economies towards creating desirable jobs in sufficient numbers. Unable, or unwilling?

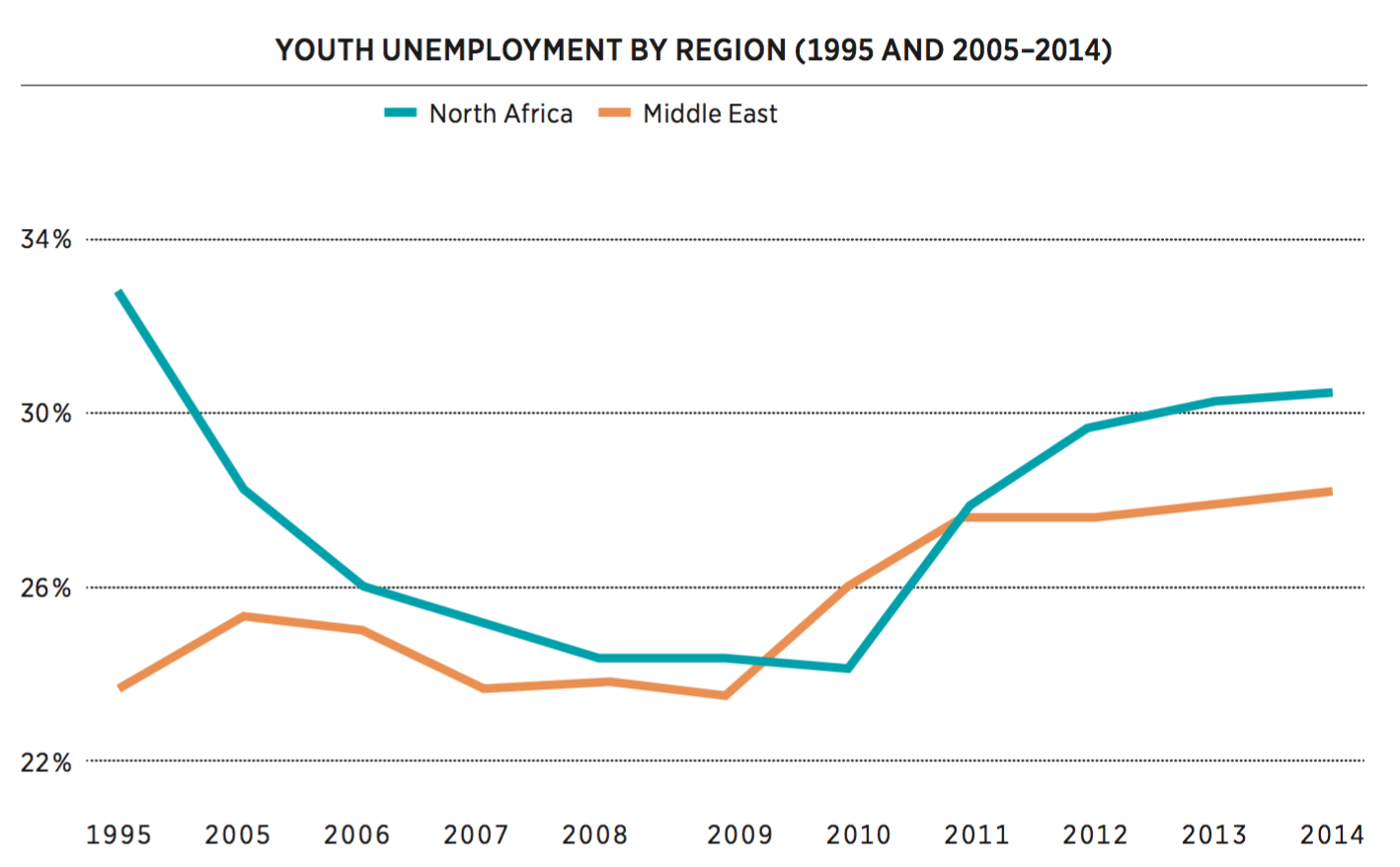

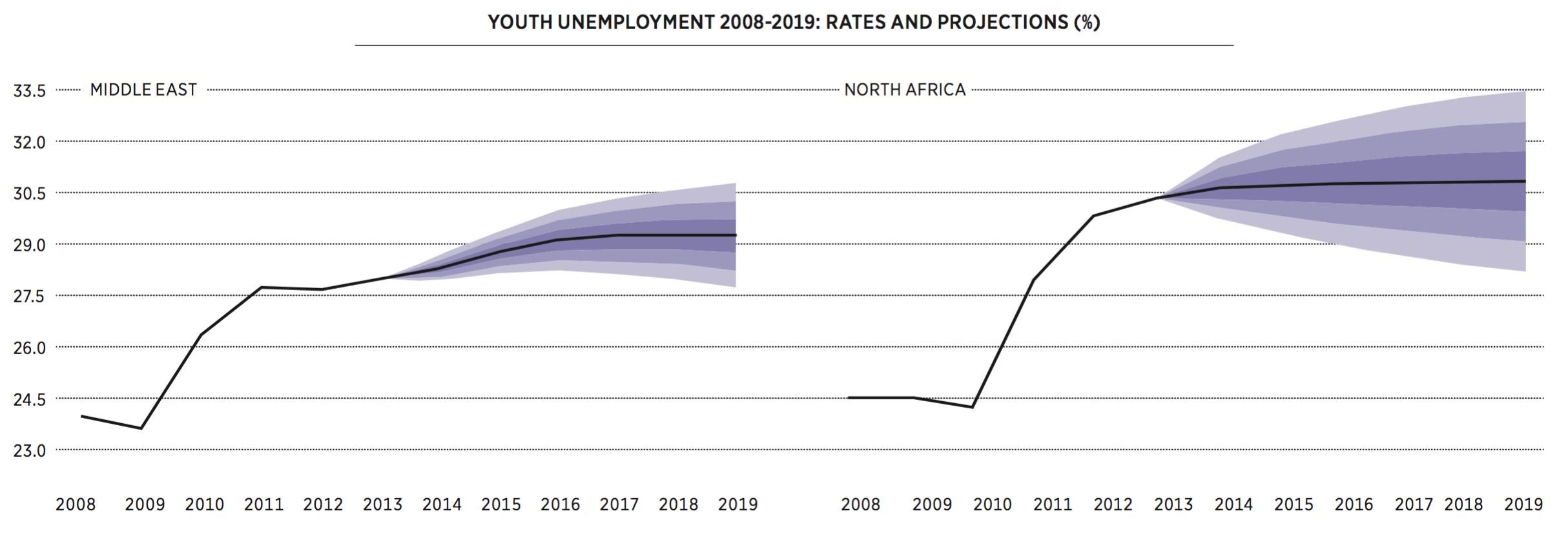

A job that pays enough to live an ordinary life, an apartment and partner and to be able to start a family: that’s the simple aspiration for most young people in the Middle East and North Africa region. But creaking economies in Arab countries means that for many the dream remains out of reach. Youth unemployment and under employment in the MENA region is the highest in the world, according to labour market figures.

This rentier system, driven by petro dollars, is a very fertile environment for crony capitalism.

And young Arabs experience less happiness and less control over their future than youth in other parts of the world, according to a survey of public opinion in the 2016 Arab Human Development Report (AHDR). They also experience less happiness than their elders – sharply in contrast with the rest of the world, where younger generations tend to be happier and more hopeful about the future than their parents.

Ensuring intergenerational equity is a worldwide concern, but youth in the Arab world seem to have drawn the shortest straw; many societies across the region exclude young people from decision making and from playing an active role in their lives, while discriminating against them in areas such as housing policy and in labour markets, says Jad Chaaban, an associate professor of economics at the American University of Beirut and lead researcher on the 2016 AHDR.

In Lebanon, being un- or underemployed often means living at home under rules imposed by the family, delaying social and civil independence and limiting chances to start a family, with marriage closely linked – through cost and social norms – to employment, says Chaaban. “Youth end up delaying their marriage, and basically living a life of frustration, because a lot of sexual relationships are forbidden outside of marriage.”

Whereas many developed countries fret about unsustainably low birth rates, Arab countries have seen population booms, with large numbers of youth now coming of working age, exacerbating demand for job creation. That demographic dynamism is at odds with the economic model in many countries in the Arab region, which is essentially restrictive and anticompetitive, with the bulk of power, both political and economic, concentrated among a handful of elites. While some countries – such as the oil rich Gulf states or Morocco – can be seen as bucking this trend, in countries such as Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt and Algeria, frustrations simmer.

These frustrations contributed to the series of popular uprisings that rocked the Arab world starting in late 2010; but despite initial optimism for genuine transitions in the region to a new social contract, progress has been underwhelming. The popular movements have been “suffering a vicious counterrevolutionary offensive”, says Nader Fergany, an Egyptian political economist.

And the civil war raging in Syria presents a dark vision of the dangers of attempting to overthrow a political regime, as well as further weighing on the region’s economic prosperity. Unemployment and a lack of purpose for youth have even helped intensify regional conflicts; the paycheque is at least one motivation to choose to join militant groups including Daesh.

An outdated social model

This landscape has its roots in the social contracts offered to citizens by populist regimes that came to power in the '50s and '60s in many countries, introducing popular measures such as free education and healthcare, while using state organs to create jobs for their citizens.

Official employment statistics in some countries can underplay the depth of the crisis by recording people who have part- time work or casual work during some parts of the year as employed. In Egypt, despite the official state statistics agency CAPMAS recording unemployment as just 12.7 per cent in the first quarter of 2016, political economist Fader Nergany believes that unemployment in the country – in the wide sense including underemployment – “is huge, no less than 50 per cent of the labour force in my estimate”.

By some measures – such as by delivering mass education and improving basic healthcare – these social contracts were successful, says Chabaan, but by many more they were not, failing to deliver on environmental problems, on political improvement or innovation, and on jobs and competitive enterprise – “all of the fields that require a social structure that is open and liberal and not subject to oppression, specifically freedom of expression”.

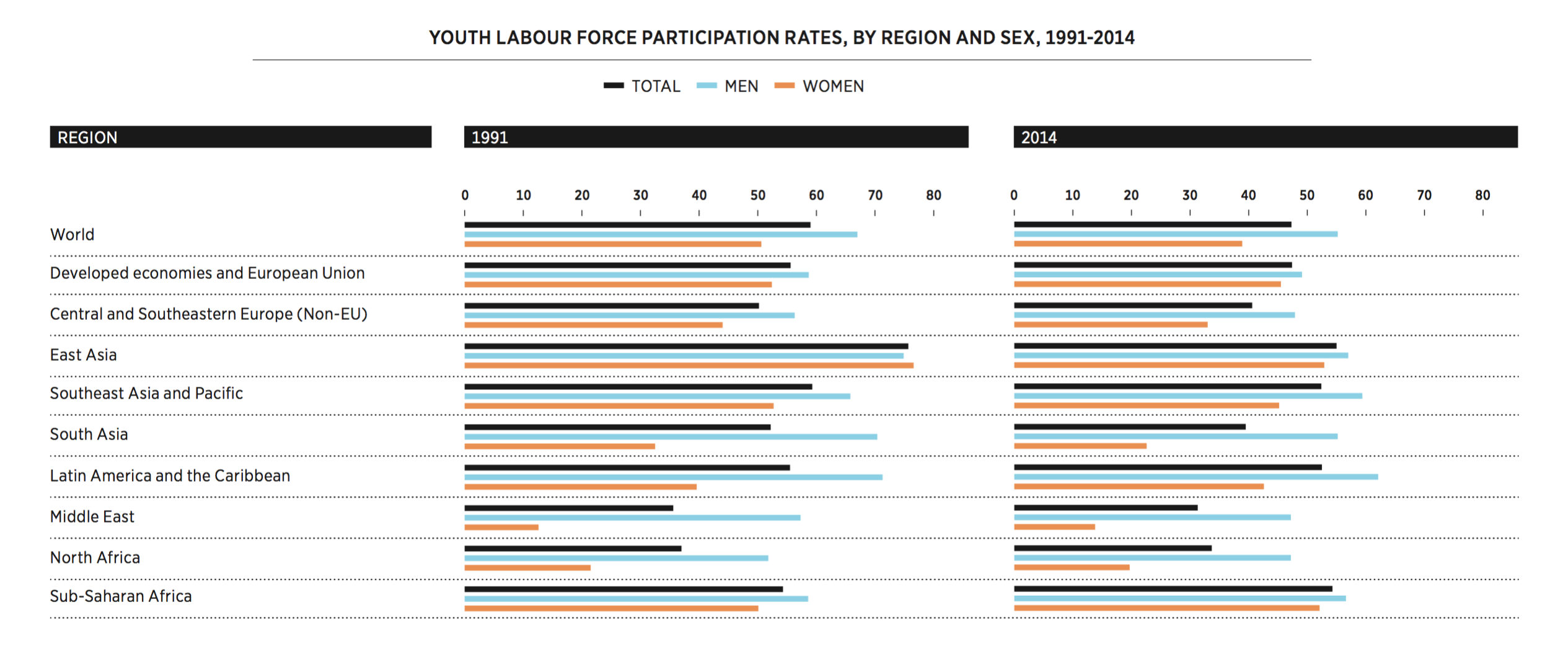

The model of using the public sector as an engine of employment growth is entirely insufficient in the face of growing populations and soaring public debt; and it is also calibrated to a patriarchal model of a family supported by a single male breadwinner, at odds with the rising levels of education among women in the region and their aspirations to join the workforce, with all the implications for personal empowerment.

When it came to their economies, most Arab states did little to pursue industrialisation or creation of competitive economic sectors; the social contract that prevailed in the region until 2011 was “a rent-based social contract, founded on a very narrow economic base, with mainly natural resources, large informal small and medium enterprise (SME) sectors, and a small formal private sector in between,” says Abdallah Al Dardari, the deputy executive secretary at the Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA), a UN agency.

In a rentier sector, businesses are able to extract profit without adding significant value, and in many cases their ability to operate in a sector or extract a resource is protected by licence or other regulation. The top rentier sectors in countries without oil resources are those associated with essential services, such as telecommunications, water, electricity, banking, real estate and national manufacturing sectors that are closed to the state, such as steel, says Chabaan.

Youth unemployment and under-employment in the MENA region is the highest in the world. Though frustrations over dysfunctional economies simmer in many countries in the Arab world, some buck the trend. By courting foreign investors and establishing itself within global value chains, in industries including automotive and aircraft parts, Morocco provides a successful example in the region.

What has fuelled rentier economies in countries such as Lebanon and Jordan has been inflows of petrodollars from the Gulf, with remittances from citizens working abroad allowing levels of consumption that are higher than could be afforded through domestic resources, says Marwan Khardoosh, an economist. “In almost every household [in Jordan], one member of the family is working in the Gulf.” These inflows have made sectors such as banking, construction and the import of goods and services highly profitable, encouraging a small number of individuals – normally aligned with political and military powers – to dominate these streams, allowing very few people to profit from these privileges, says Chabaan. “This rentier system, driven by petro dollars, is a very fertile environment for crony capitalism.”

He contrasts rentier sectors with innovative and fast-moving industries needing many productivity changes. “If you have a big manufacturing export sector, then it’s very unlikely that cronyism will prevail, because you have serious competition driven by external markets. What we have is a closed system of dependencies.” And when compared with cronyism in developed countries (for example in Berlusconi’s Italy), its repercussions in the Arab region are magnified by the lack of social safety nets, says Chabaan. “If you have a problem in your company because your competitor is a very big monopolist and a crony, you can't attack them in court because the courts are dysfunctional. If employees lose their jobs, there is no unemployment benefit, there is no social security, there is no free healthcare."

Mapping MENA’s Corruption

For citizens in many countries in the MENA, corruption is a fact of daily life. A survey published this year by Transparency International found more than 60 per cent of respondents expressing the opinion that corruption in the last 12 months had worsened (Yemen and Lebanon were the worst offenders, while Morocco and Egypt performed best). A third of people also reported paying a bribe in the last year, most commonly in interactions with the courts or police, to obtain a document or permit, or at a public clinic or hospital. Corruption also makes an economy less attractive for foreign investment. A businessman in Jordan says that despite good attempts in recent years to fight corruption in the country, it remains “rampant across the economy”; he’s heard firsthand of foreign investors who were deterred from pursuing their investment plans in Jordan as a result of corruption such as bribetaking.

Measuring income inequality in the Middle East is hampered by a lack of accurate data on a national level, according to research published last year by Thomas Picketty and Facundo Alvaredo, but they found that across the Middle East as a whole income inequality is extremely large, far outstripping the United States and Western Europe.

Yet whereas basic transactional corruption is experienced by citizens in an obvious way, corrupt deals made behind closed doors between a tycoon and a politician, for a state contract or concession, are less obvious but have the potential to have profound and damaging effects on the economy of an entire country. Corruption blunts the job creation potential of public investment, while investing in infrastructure is a proven method of job creation. In the Arab region, that effect is less secure because so much of a public infrastructure project’s budget is normally lost to corruption, says Al Dardari.

Corruption and cronyism can even direct an entire country’s industrial and investment policies. The best evidence of this comes from Tunisia, where during the 1990s and 2000s, just 220 businesses, all owned by the family of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, were able to rake in 21 per cent of Tunisia’s net private sector profits while accounting for approximately three per cent of private sector output, according to a World Bank working paper. That higher profitability didn’t come because the Ben Ali firms were better managed: analysis of changes made to Tunisian industrial policies and its investment code revealed they had been manipulated to boost the position and market access of family-owned firms.

In one example, Sakr El Materi, who married Ben Ali’s daughter Nesrine in 2004, purchased a publicly owned car dealership in 2006 for 22 million Tunisian dinars; after the deal, the quotas for import of cars awarded to dealership increased almost fourfold. Three years later, just 40 per cent of the company's capital was sold in an IPO for 53 million dinars. These manoeuvres attest to an “insidious association between regulation and cronyism”, demonstrating that “proliferation of regulation may be a vehicle to expand state capture” said the report. Beyond problems of justice and social equity, this kind of protectionism allows large companies to pursue profits domestically without needing to produce tradable goods and services that can be exported abroad, says Caroline Freund, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and one of the report’s authors. It’s also a pattern she discerns in many countries in the region. “What the MENA countries need is more competition and greater incentives for resources to go to their most productive uses.”

Politically connected firms don’t reap disproportionate profits in a vacuum; the impacts of their patronage are felt across an economy. In Mubarak’s Egypt, politically connected firms received special treatment in numerous ways, including benefiting from subsidies, trade protection, access to land at below market cost, biased regulatory enforcement, and subsidised borrowing from state banks. Significantly, the presence of a connected firm affected the aggregate growth of all companies in that sector, according to another World Bank working paper. When businesses have comparable cost structures, they are incentivised to pursue productivity growth, such as adopting new technology or investing in training – but when leading firms have advantages through political connections, they have no need to invest in greater productivity. At the same time, trailing firms perceive that they have no viable way of being competitive, miss out on investment and tend to use vintage production technologies, focusing on local market niches to survive; unconnected firms may even choose to stop growing to stay under the radar.

Official employment statistics in some countries can underplay the depth of the crisis by recording people who have part-time work or casual work during some parts of the year as employed. In Egypt, despite the official state statistics agency CAPMAS recording unemployment as just 12.7 per cent in the first quarter of 2016, Fader Nergany believes that unemployment in the country – in the wide sense including underemployment – “is huge, no less than 50 per cent of the labour force in my estimate”.

That dynamic helps explain why so much of Egypt’s private sector employment is now concentrated in small businesses, with firms with fewer than ten employees accounting for 72 per cent of aggregate employment. In their conclusion, the report’s authors suggest that the evidence of cronyism and its effects serves to “cast doubt on the feasibility of industrial policy under a closed political system”.

Noting that industrial policies have failed in Egypt and Tunisia, it suggests that industrial policies – considered by many analysts to be an essential part of a successful development drive in the Middle East – “cannot work effectively in environments dominated by rent seeking”. If Middle East policy makers want to tackle corruption, crony capitalism and monopoly rents in the private sector, countries need to improve their investment codes to support competition and enforce it fairly, believes Freund, a former MENA chief economist at the World Bank. “The problems include a weak investment code and variable enforcement, where insiders get better treatment than outsiders.”

Nevertheless, the example of Tunisia suggests that a solutions will not be quick or easy. Since 2011, there has been a blossoming of decentralised corruption – paying bribes to police or trafficking of goods at the Libyan and Algerian borders – says Mouheb Garoui, executive director of I Watch, a Tunisian NGO connected with Transparency International. That’s partly due to the lack of meaningful political leadership since the revolution, he says, but whereas during the Ben Ali era corruption took place at the national and international level, his grip on power prevented it happening at a lower level. With the spotlight focused on large scale corruption after the revolution, it has now moved to target people's daily lives and their needs.

Solutions Grand and Simple

In observing the various problems of the Arab world, it’s perhaps not surprising that many experts look at the European Union as a potent example of what regional integration might be able to achieve, transforming a continent wracked by war into an economically interdependent trading bloc. But despite the lip service long paid to notions of greater Arab unity, when it comes to practical steps there’s been little progress. Even when there are notable achievements – such as the Greater Arab Free Trade Area (GAFTA) – critics charge that they’re frequently undermined by poor implementation.

Right now we can’t focus on just economic growth and liberalisation of markets as a solution, we need to go back to the fundamentals.

What may perhaps give proponents of greater regional integration hope is the humble beginnings of the EU, as a body to regulate the steel and coal market. Janmejay Singh of the World Bank says that they’re trying to promote regional cooperation in the MENA on public goods like water, energy and education, believing that if countries can cooperate at a sectorial level, that can have a spillover effect at the political level. Coal and steel were “a pretty narrow interest that brought the European countries together for the first time”, he notes.

ESCWA has produced a number of reports on regional integration, including modelling economic advantages of greater trade integration, and Al Dardari believes that the cause of Arab trade integration is becoming much more accepted at a government level. “There is a sense that too much dependence on global growth levels as a driver of growth in each Arab country is no longer working, given that there is practically a flat growth rate at a global level.” He also discerns greater cooperation in areas such as the movie industry, television production, fine arts and even tourism. “The problem is that this is happening at a time when instability is wreaking havoc in the region.”

The simplest formulation of why regional integration would benefit economic growth is that in total the MENA region has around 355 million inhabitants, but presently most companies in the region have trouble trading beyond their borders, because of inadequate infrastructure, antiquated legislation or even outright protectionism.

Creating a larger marketplace would allow industrial competitiveness to start emerging and increase levels of foreign investment, while developing economies of scale would see resources more efficiently allocated as well as produce important flowon effects such as a viable investment environment for R&D, believes Al Dardari.

Having Arab companies move up the value chain by investing in R&D and becoming part of global trade networks is necessary for widespread creation of wellpaying and socially protected jobs in the private sector, especially in manufacturing and industrial sectors, says Al Dardari. Currently sectors such as the textile industry depend on low labour costs as a source of competitiveness, meaning that as competition rises in the globalised economy there is downwards pressure on wages. “It’s a vicious circle,” he says.

Yet despite clearly articulated benefits, many experts in the region are pessimistic about chances of greater integration. Chances for beneficial Arab integration have sadly dwindled recently, says Fergany. If he sees one positive sign for Arab integration, it is in civil society organisations establishing pan-Arab networks, especially in the fields of human rights and women's rights, despite efforts by Arab governments to “tighten the noose around the right to organise in civil and political society”. Meanwhile, given that existing regional integration initiatives in MENA have all been poorly implemented, opening unilaterally to trade and foreign investment is more important than regional integration, believes Freund. “It’s more important for countries to focus on getting their own policies right.” Moreover she does not perceive any “strong momentum for regional integration right now”.

And as much as regional integration can be couched in terms of economic benefits, that process – likewise with unilateral market liberalisation in any Arab country – has a significant political dimension as well as the potential to undermine the economic dominance of regional elites. Shifting to more productive economic modes will also require that political leaders make greater use of the macroeconomic policies used to effectively manage modern economies, such as fiscal policy, monetary policy, taxation and public investment, says Al Dardari. (With the benefits of subsidies disproportionately accruing to the wealthy, these are also in need of reform – the MENA region accounts for three per cent of the world's GDP and population, but has over 50 per cent of global fuel subsidies, says Singh.)

In the vein of ‘no taxation without representation’, moves towards more participation of citizens in the economic production process will affect the whole the social contract, bringing sensitive questions of political participation, governance, transparency and accountability to the forefront, he says. “When we talk to senior level Arab government officials, they recognise this, they know it's difficult, but they recognise that shifting the economic relationships within the society will require a different social contract.”

Regional elites need do little to maintain economic dominance other than drag their heels. Jad Chaaban notes that while exclusionary policies may be deployed to protect interests, a freeze on policies or reform (Chaaban identifies this tendency in Egypt, Lebanon and Jordan) “is as bad as being actively involved in the negative sense”.

Given the stalled situation of many economies, some are reluctant to look for grand solutions, or to look to the political elites – who have the most to gain from the maintenance of the status quo – to deliver significant transformations. Chabaan believes that change can best come incrementally and in piecemeal fashion. “Right now we can’t focus on just economic growth and liberalisation of markets as a solution, we need to go back to the fundamentals and think whether enough kids are being taught the right things in schools and if they are able to find good housing when they graduate from university.”

And while current structures may be corrupt and out dated, they’re the only ones available that can minimise conflict, says Chabaan, backing away from any suggestion that increasing pressure from demographics and widespread unemployment will push individual countries towards a boiling point. “The boiling point is always kept down by the risks of chaos. People are wary of facilitating a boiling point because they hate violence, they're sick of conflict, and many Arab countries are in conflict, either active or delayed conflict.” At the same time, a large swathe of the population directly profits from the state or benefits from special access to services while the silent majority remains traditional and wary of big shocks to the system.

Meanwhile, engagement by the international community “has to be done in a way that empowers the people of the region, and not create conditions for the maintenance of these repressive powers”, he says. The international donor community and other entities should focus on greater engagement with existing structures in the region, such as schools and universities and even local public powers like municipalities – “entry points that would strengthen public services and improve social programmes that cater for the excluded, including young people and old people”.

Al Dardari believes there is a tendency to underestimate existing levels of integration in the region, and in its “tremendous potential”. He points to the popular uprisings as a sign of how acutely the destinies of Arab countries are linked. “One young man burned himself [to death] in central Tunisia, the whole region is burning. How more integrated – culturally, emotionally, psychologically and even politically – could the region be?”