Ethiopia sees rapid change – so what can we learn form a collection of pictures of every-day Addis Ababa citizens during the 1940s to the 1980s? Anna-Theresa Bachmann discusses this with Wongel Abebe, who recently launched ‘Vintage Addis Ababa’.

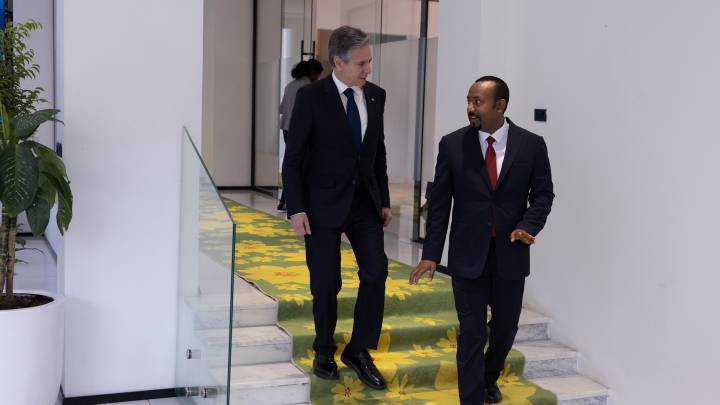

zenith: Under the leadership of the freshly elected prime minister Abiy Ahmed, it appears that a new chapter of Ethiopian history is currently being written. Why was it important for you to publish a photo collection which draws attention to the country’s past?

Abebe: When we started working on this book two and a half years ago, we were still living under the state of emergency. It is a pure coincident that ‘Vintage Addis Ababa’ came out at this hopeful time. Right now, young Ethiopians find themselves in a huge identity crisis. Especially in urban areas like Addis Ababa. Growing up on social media, you are a global citizen as well as Ethiopian; you are Addis Ababian but you are also African. It can be confusing: Who am I? What are my values and what is my culture? If you do not know where you come from, you do not know where you are going. For me personally, putting together the book has been a quiet a journey.

In what sense?

I had many misconceptions about the past. Growing up I did not realize that there was sometimes a contradiction between narratives. In school we learn about the dark past such as the Red Terror, about famous people, the ruling class. My grandparents on the other hand told me about what normal life was like. I was never able to connect these stories. What makes ‘Vintage Addis Ababa’ powerful is that history becomes relatable: Through every day-citizens we learn valuable lessons about life, about priorities and relationships. Just because most of the pictures are in black and white, we tend to think that life back then was very different from ours. But for the people, it was colourful, too.

Was is difficult to convince people to share their private collections with you?

Sometimes, they would be critical at first. But when we explained the project, they were on board. Most of them came to the book launch event in November 2018. It was a very moving moment to see them all together. They felt valued because elderly people often think that the young generation does not want to listen.

How does ‘Vintage Addis Ababa’ fit in the city’s contemporary art scene?

The art scene in Addis Ababa is very vibrant, and you find different projects across the fields of photography, music, fie arts and literature such as Girma Berta and the GBOX Creative. They are getting international recognition. Setting a narrative for yourself is something that is very important at this stage, not only in Ethiopia, but across Africa. You find those movements which try to look back via social media, such as Old Photos of the Horn of Africa.

Despite the book’s aim to tell Ethiopian’s history in contrast to decades of the Western colonial and aid worker’s gaze – as writer Maaza Mengiste writes in the introduction –, ‘Vintage Addis Ababa’ relied largely on Western funds.

This caused quiet some discussion at the book launch event and on social media. To be honest, it is heartbreaking to not get funding from Ethiopian organizations for art-related projects. Private businesses fund concerts but are reluctant towards new things. This causes a huge lack of funds supporting artists. I run a media company that has been trying to publish a comic book for three years. It is a satire critique about modern Ethiopia, written in Amhaaric as we want it to be accessible for everyone. But getting funds is very hard.

Do you think the new leadership might step in and allocate some funds for the art scene?

The government can play a certain role, especially the Ministry of Tourism and Culture. But we should not wait for them, it should be a bottom-up process with businesses acknowledging the power of art to change culture and to change people.

If you were to publish another version of ‘Vintage of Addis Ababa’ in 30 years from now, how would it look?

We had a similar discussion at the book launch, asking if Addis Ababa would still represent the whole of Ethiopia. Because 50-60 years ago, Addis Ababa was still a small town with many people from different regions passing though. They represented the diversity of the country. But today, we stand at nine million people, including the periphery. The communal way of life you see in the book has also changed. You will still find it in rural communities. Everybody used to be everybody’s business, a child used to be raised by a whole street. But in the city today, we live a very isolated life without knowing our neighbours. The focus is no longer on relationships. It’s on work and careers. Unless we do not take ownership and change the things we do not like, I am not sure we will be proud of our stories.

More than fifty percent of Ethiopia’s population is younger than 25. This seems like a huge force to push things forward.

The community is not one of the people’s priorities right now. Many young people have no jobs and education is bad. They envision their future in the form of a one-way-ticket to Europe or the US. But I hope that the new leadership will inspire them to think about what they can give instead of what they can get. The West does not perceive the government as a real change, since Abiy Ahmed still belongs to the same old party. But within the country is a true sense of optimism which caused even a lot of people living in the diaspora to come back.