Ethiopian journalist Tsedale Lemma on unsettled scores between Sudan and Ethiopia – and why Zanzibar may hold the key for peace in the Horn of Africa region.

zenith: How does the ongoing conflict in Sudan impact Ethiopia?

Tsedale Lemma: People want to escape the violence in Sudan. Western Ethiopia, along the borders of the Amhara region, is a place of refuge for many Sudanese. But we hardly have the capacity to take them in: Ethiopia already has to care for 4.5 million internally displaced people.

What’s the state of bilateral relations between Ethiopia and Sudan?

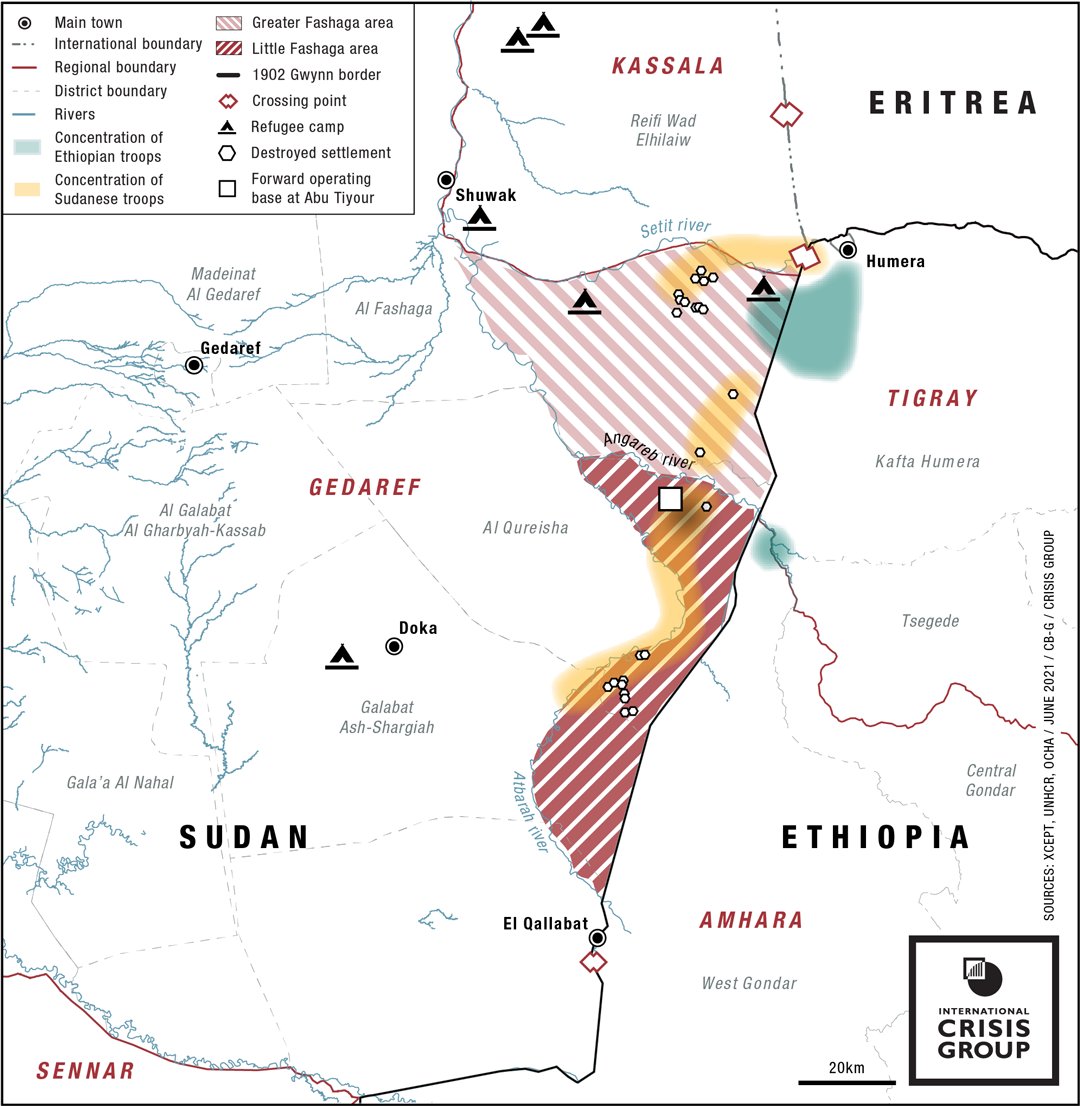

For almost two years, tensions have been mounting, stemming from a 30-year-old border agreement. Ethiopian farmers were originally allowed to cultivate their fields in the fertile areas in Al-Fashqa – to which both Sudan and Ethiopia formally lay claim. The Sudanese army under Abdulfattah Al-Burhan then took control of the area in 2021 and expelled the farmers. Ethiopia may try to take advantage of the instability in Sudan to change the facts on the grounds again. However, I also believe that both countries are mired in internal conflicts at this stage. Meaning, no-one is keen on opening another frontline.

Both countries are also dependent on water resources from the Nile.

The »Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam« has been a potential source of conflict in the region for years. So far, Sudan has positioned itself as a big stakeholder between Egypt and Ethiopia. It is possible that Cairo is now hedging its bets for support in the negotiations with Addis Ababa by supporting allied militias in Eastern Sudan.

To what extent is Eritrea involved in the conflicts in the region?

Eritrea's interference is causing a lot of geopolitical problems in the Horn of Africa region. The regime of Isaias Afewerki, for example, sends soldiers across the border to support allied factions within the East Sudanese rebel groups. Historically, Eritrea is experienced in interfering in fragile situations in order to benefit from them: for example, in Yemen, Somalia, Djibouti and also in Ethiopia.

‘The Ethiopian government should therefore take the issue of accountability seriously in order to set a precedent’

Despite the peace agreement last autumn, Eritrean troops are said to be still present in the conflict region of Tigray in northern Ethiopia.

Yes, Eritrean soldiers continue to occupy certain areas, especially in north-eastern Tigray. The Irob and Kunama minorities are particularly at risk here, especially as no humanitarian aid is reaching these areas. According to local administration, Eritrean troops are also obstructing the African Union (AU) teams that are supposed to monitor the implementation of the peace agreement.

US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken has publicly called for accountability for war crimes related to the Tigray war during his last visit to Ethiopia in March. How viable is that prospect?

I have great concerns about that. Especially because the Ethiopian government insists that such proceedings ought to be based on national legislation – and not on international law. I think there is enough evidence for a charge of crimes against humanity – I personally also think what happened in Tigray can be classified as genocide. However, Ethiopia still does not allow for independent investigations conducted by the United Nations, which would be a prerequisite for accountability.

Can legal accountability help dealing with future conflicts?

Absolutely. After all, Ethiopia is mired in a dozen of conflicts that break out again and again and turn into militarized violence: in Tigray or Oromia, for example. The Ethiopian government should therefore take the issue of accountability seriously in order to set a precedent for conflicts that continue to smolder.

Barely 4 years ago, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed was awarded the Nobel Prize for the peace agreement with Ethiopia’s former arch-enemy Eritrea.

And yet he was responsible for one of the most devastating wars in our history. The Nobel Prize does not make him a peacemaker. The course for escalation was set at the very beginning of his term in April 2018: Assassinations of high-ranking local politicians and public figures in Oromia and Amhara, for example, were not prosecuted. This lack of accountability has changed the political dynamics in the country.

‘We should finally seize the opportunity to create a state that is as diverse as the country itself’

The armed conflict between the central government and the Oromo Liberation Front (OLA) has been going on since 1973.

The war in Tigray has been overshadowing the Oromo conflict for the last two years. On the other hand, it has revived the involvement of the international community: as imperfect as the peace in Tigray is, it shows that even with conflicts that seem hopeless to solve, peace is possible.

Who is driving these efforts to resolve the Oromo conflict?

The governments of Norway and Kenya as well as the East African Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD). The first round of negotiations started in May in Zanzibar. The involvement of external actors such as the EU is also welcome, at least in principle. However, the warring parties cannot agree on what role Brussels, or the United States should play in the peace process. One thing is clear: the economy is tanking and the Ethiopian government is not capable of shouldering another war.

How does the situation in Ethiopia affect security and stability in the Horn of Africa region as a whole?

In the three decades before Abiy Ahmed took over, Ethiopia was a stabilizing factor in a troubled region – and prevented, for example, the Somali terrorist group Al Shabab from spreading out further. Since the Prime Minister joined forces with Eritrea’s dictator Afewerki, we have fallen from an anchor of stability to the most fragile state in the Horn of Africa region. Ahmed fails to contain his allies: Eritrean troops refuse to withdraw from parts of Tigray. And the local Amharan militias that fought alongside the Ethiopian army will not be disarmed so easily and are also making their own territorial claims in Tigray. One conflict is therefore fueling the next: the Tigray conflict is followed by the Amhara conflict.

How can this cycle be broken?

If Abiy Ahmed continues like this, he will be nothing more than the warlord of Addis Ababa – shifting alliances with local militias and arming certain sections of the population will not restore the sovereignty of the central state. However, the state governments also deserve some of the blame. They are equally obliged to respect the constitutional order. Above all, the state must confront Ethiopia’s complexities. Dealing with diversity has made Ethiopia a sinking ship over the last 50 years. Now we should finally seize the opportunity to create a state that is as diverse as the country itself.

Tsedale Lemma