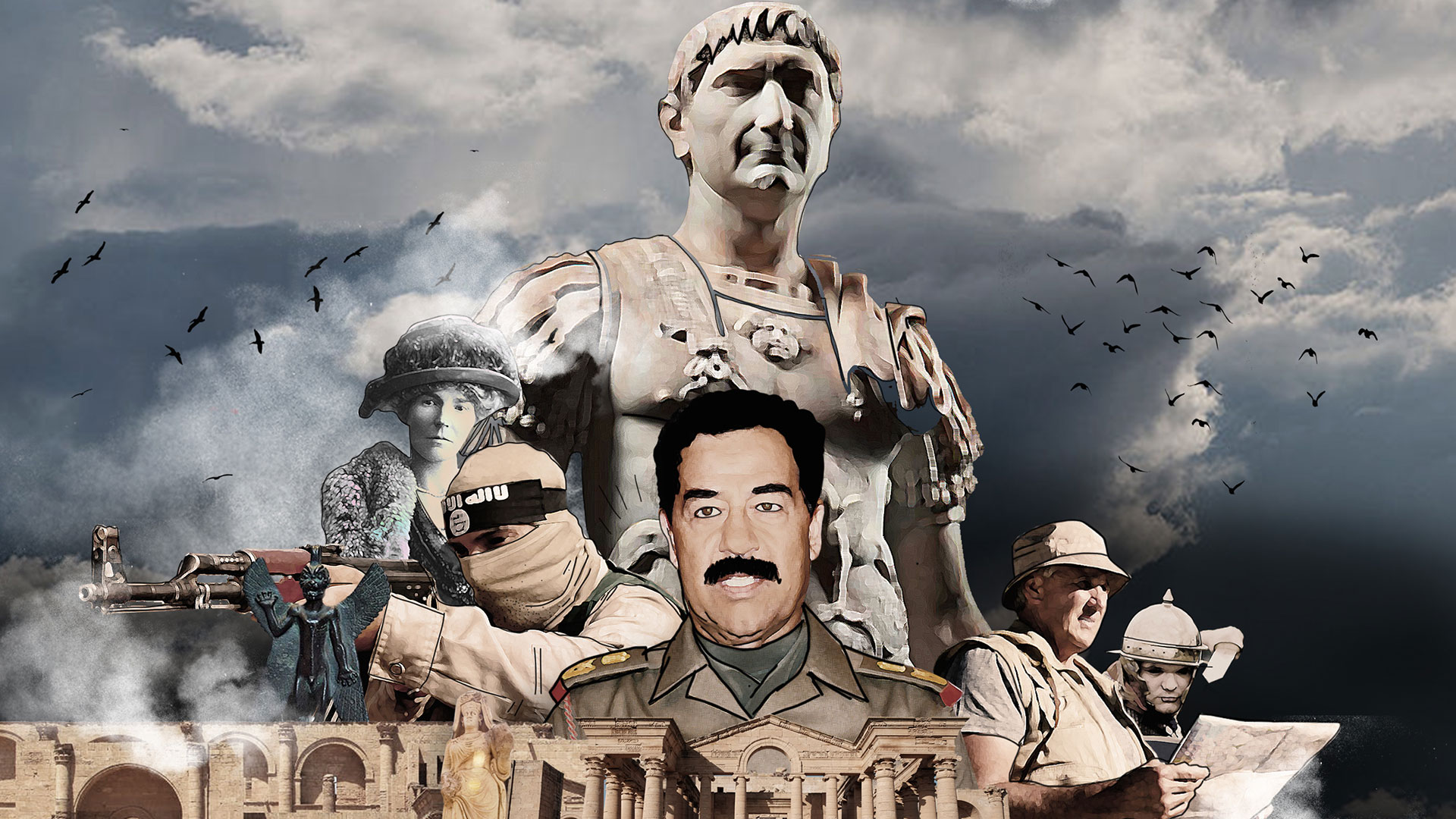

Unravelling the real secret of Iraq’s Desert Queen.

There are no borders; there aren’t even roads – it’s best to come here by horse or four-wheel drive. At the beginning of the year, the Jazeera is covered in a sparse green fluff of grass. It owes its name (‘island’) to its location between the Euphrates and the Tigris. If you drive off-road to the southeast of Mosul and continue west through the Upper Mesopotamian steppe, you’ll eventually end up in Syria. Before that, you cross a border that the Almighty did not anticipate when he created the Jazeera. Tribes, semi-nomads and shepherds, as well as the jihadists of the so-called Islamic State (IS) used to cross it easily, and possibly still do at night, without headlights.

There is a lot of smuggling going on in the Jazeera, somewhat overshadowing its honourable reputation as an old trade route. A strand of the Silk Road ran through here. This old route crosses the Wadi Tharthar, which eventually flows into Iraq's largest lake. The river water tastes salty and bitter, enjoyed only by Bedouin horses. This morning, haze is settling over the wadi.

If IS insurgents are still roaming here, you shouldn't drive in the fog. Just two days before my trip, Iraqi security forces and paramilitaries raided the area and found equipment for booby-traps – wireless detonators, cables, shell casings and torn-off epaulettes which the insurgents may have used to pose as police. There is still occasional gunfire, and some roads may still be mined.

The concrete bridge that once spanned the wadi looks like a toy set smashed by an angry child. Two small, expertly placed explosive charges were enough to make it impassable forever. "Daesh,” comments a militiaman of the Popular Mobilisation Units Al-Hashd al-Shaabi laconically. Then he points to the left, where the supply road bends and an improvised steel bridge crosses the wadi. "Hashd,” he adds with a certain pride. Not only are they a fierce bunch of paramilitaries taking down IS with its own methods, but they are masters of engineering and pioneering too.

The sight of the destroyed bridge is nevertheless an ominous sign: What did the jihadists do to Hatra, the Queen of the Desert, which lies behind this wadi?

The sun is low enough to bathe the ruins of Hatra, visible from afar, in a dramatic light. In ancient times this was the centre of a trading city, possibly even the capital of an Arab kingdom with features of Roman, Hellenistic, Arab and Persian culture. The iwans, the arched, open vaults of the main buildings, tower high. Their majesty still gives an idea of the impression they must have made on caravan riders some 1,800 years ago, after days of riding through steppe and desert. From the high back of a camel, they must have looked more majestic than through the dirty windscreen of a Toyota Land Cruiser.

Hatra's buildings could be compared to the Cologne cathedral, Luxor Temple, the Pantheon in Rome. Who came up with the idea of building such a superb architectural complex in this wasteland – and above all, why? It has been a mystery for a long time.

The outer walls of the ancient city and its sanctuary are still clearly visible. Bedouin shepherds have pitched their tents in the courtyard of the complex, and a pick-up truck of the paramilitary unit Ansar al-Marja'iya (‘followers of the highest Shia clergy’) is parked under a magnificent iwan, heavy machine gun installed on top.

Who hasn't experienced this? You host a sumptuous party with food, cold drinks, live music. And yet some guests complain: they had to walk for kilometres and are already sweaty, because they couldn't find parking. Walter Andrae, an archaeologist in the service of the German Oriental Society, probably thought in a similarly practical way when he first looked at the ruins of Hatra in May 1907 and entered the courtyard covered with large limestone slabs: “This enormous, open space quite strikingly characterises the palace of the desert prince who had to accommodate the animal-rich caravans of his distinguished guests.”

“It it too wonderfully interesting!”

Andrae, who had a special eye for Hatra's architectural features, was enthusiastic not only about the stylistic variety of the complex. He also recognised the experimental approach of the ancient stonemasons and their wide-span, precisely calculated barrel vaults. One could “comfortably accommodate a four-storey apartment building inside”, he wrote in his campaign report, further praising the “halls of princely dimensions and vaults whose constructors are worthy of all respect”. Andrae was leading excavations in Assur on the Tigris some 100km away and had taken up quarters there. The man from Leipzig Anger-Crottendorf obviously did not want to spend the night with the Bedouins, who regarded Hatra as “their property”. Dutifully, he took a ride around the traces of the ancient city wall.

Four years later, in April 1911, famous British Orientalist Gertrude Bell drove her mount over Hatra's hill with no less enthusiasm, but obviously greater pleasure than Andrae. One could not have a heavy heart in such a place, she wrote to her stepmother: “It is too wonderfully interesting.” Bell snapped a few photos of the Ottoman cavalry, which had just set out on a punitive expedition against the Shammar Arabs, then passed the time escaping from her escort.

Of course, Bell did not question the opinion of the esteemed expert Andrae, which was based on a superficial survey but conclusive. She too thought the gigantic complex was a palace. Visiting Hatra without in-depth prior knowledge, how could one come up with anything else?

However, the wall which divides the complex into two sections does not fit into the picture at all. It looks as if two ill-tempered heirs of the ‘desert prince’ had decided in a quarrel to turn the palace into two unequal areas of a semi-detached house., raising a massive wall through the front garden. Structural remains in the tunnel vaults that look like altars intrigued later archaeologists: Were the rulers of this house so pious that they put a chapel for prayer in every room?

Further research in the course of the 20th century revealed that the Ivan complex was not a palace but a group of temples, part of a multifunctional pilgrimage site. In Hatra, one could apparently pay homage to the entire pantheon of the late Ancient Orient – it was a kind of pre-Islamic Mecca, an Oriental Capitolium. When Hatra experienced its heyday at the end of the second century AD, these deities had merged into a triad with the sun god at their head, as an integrative religion in which Romans, Greeks, Arabs, Parthians and other peoples and cultures found themselves, possibly also the early Christians among the Arabs of the ancient Orient.

Anyone who wonders why a city in the middle of the steppe needs such spectacular sacred buildings should consider the location. It was not the last time in history that remote places reinvented themselves as tourism magnets by means of a miracle and a magnificent site of worship. Beit Allaha, ‘house of God(s)’, is what later archaeologists and epigraphists called the temple complex. Hatra was a city that lived on trade and knew migration as the norm.

Aramaic was probably the lingua franca in Hatra, as numerous inscriptions testify. The population of the city consisted partly of sedentary tribes and partly of nomads who settled in Hatra only seasonally – a “dimorphic society”, in the words of German historian Michael Sommer, which can still be seen today in the aerial photograph of the settlement structure. Hatra’s heyday came in the Parthian period in the second century AD, with many statues and objects bearing witness to the influence of this Persian kingdom. From the middle of the 2nd century, the designation ‘King of the Arabs’ appears in inscriptions in connection with Hatra's rulers; little else is known about them. Some texts feature the names of an Aramaic-speaking dynasty of princes, though it is not known whether and when these protectors of Hatra's temples ruled independently, or whether they were clients to the Parthian dynasty.

The Jazeera in which Hatra lies may not know a natural border, and the dividing line drawn by the Britain and France in the 20th century between Syria and Iraq may be artificial. But this was a borderland even thousands of years ago, the ‘blood lands’ of the Orient, to use a term from contemporary history. On the great frontier of empires, different rules applied. Army commanders literally let their hair down. No prisoners were taken.

An Oriental Capitolium in the Blood Lands

Whoever crossed over to the eastern bank of the Euphrates had to know what they were getting into. The Roman Republic experienced its first Waterloo there in June 53 BC, at Carrhae (now Harran) in the now Turkish part of Upper Mesopotamia. No less a figure than Gaius Crassus, the triumvir and proverbially the richest man in the Republic, lost five legions, his son and ultimately his own life in the Jazeera. The Parthians had mocked him when he threatened an invasion, asking whether it was Rome's decision or that of a vain old man.

A legitimate question, since Crassus' invasion of Iraq was quite unpopular with the Roman people. After making the legions thirsty and weary with their banter, the Cataphracts, the Parthian armoured horsemen, rolled down everything that was left of Rome’s expeditionary army. An unimaginable 20,000 soldiers are said to have fallen in battle or by mass execution. The Crassus campaign against the Parthians is regarded as the most disastrous military decision in the history of Rome.

One and a half centuries later, emperor Trajan marched out against the Parthians but failed to conquer Hatra. Septimius Severus, the Libyan on Caesar's throne, made a similar attempt but then preferred to focus on lower-hanging fruit. Hatra brought no luck. The city, where Arab allies of the Romans seemed to come and go, continuously held out against the Imperium Romanum even after Syrian Palmyra, Hatra's sister, had long since been defeated. Later, in the middle of the 3rd century, the city sought help from Rome of all places when a new Persian dynasty was on campaign to conquer Mesopotamia. Inscriptions testify to the presence of Roman soldiers in Hatra.

The Sassanids had overthrown the Parthian dynasty of the Arsakids and now, at the beginning of their reign, put an end to Hatra’s prosperity. The armoured camels of the Hatrenians were no longer sufficient for defence against the mighty forces from the east. Nor did the pantheistic sanctuaries in the city impress the lords of the Sassanian empire – they did not mind their subjects worshipping different deities, but had a particular antipathy to pagan temples that could attract large crowds of believers and eventually lead to political unrest. Unlike the Parthians in Hatra, the Sassanids worshipped one supreme deity, Ahuramazda, who revealed himself in fire, not fancy statues.

In the 20th century, another leader emerged to make Hatra a stage for his own glory. Saddam Hussein, the self-proclaimed heir of Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon, took power with his Baath Party and had the ruins of Hatra, especially the collapsed iwans, lavishly reconstructed. The city's history was apparently too complex and unexplored to make a grand narrative for itself. But after all, Hatra is not far from Saddam's hometown of Tikrit. Some of the stones used for restoration bear his initials.

Shortly after Saddam and his troops, an even stranger force entered Hatra armed with spotlights, cameras and legions of extras. A Hollywood team had discovered the magnificent temple complex as a film set for the 1977 supernatural horror classic The Exorcist. In the prologue, for which an excavation was staged next to the Beit Allaha, Jesuit priest-turned-archaeologist Max von Sydow digs up the statuette of a Mesopotamian wind demon. In truth, we know from Babylonian records that this spirit, Pazuzu, was not such a bad fellow. In the movie, however, the statuette is inhabited by a demon, and so the horror takes its course. Hundreds of Americans had to receive medical treatment after watching the film, which was quite extreme for its time. Moreover, the crew at some point feared that an actual demon had entered the production. A set burned down, then two of the crew died suddenly back home in America.

Not until three decades later did American commands echo again in the vaults of Hatra. This time, in 2004, it was not director William Friedkin and his team, but the officers of the 101st Airborne Division. Saddam had been ousted, ancient sites had been partially looted, and the US soldiers had found an Iraqi guide who gave them an ‘exorcist tour’ of the ruins. (At least that's what the British Telegraph reported at the time.)

Just a few years later, Hatra became a no-go area. A Sunni insurgency was brewing between Mosul and Tikrit and after dark, IS in Iraq would take control of both banks of the Tigris and parts of the Jazeera. Eventually, in 2014, the jihadist brigades moved into Hatra during daylight. The temple complex seemed like an ideal shelter. The Iraqi air force and its allies would not drop bombs there, and parts of the site were covered by the magnificent vaults and ceilings and thus not accessible to reconnoitring drones. So the insurgents used the ruins as a workshop, stuffing vehicles with explosives and detonators to use them as deadly weapons against armies and civilians alike. Hatra’s multi-storey structures also provided a training ground for urban warfare. Bullet casings can still be found in every corner of the site.

The jihadists did not know to what extent they must have hated what Hatra really stands for

With the destruction of ancient statues in the Mosul museum by IS insurgents, and seeing what they had done to Palmyra and the Assyrian ruins of Nimrud with plastic explosives and bulldozers, Hatra could not expect to be spared. A propaganda video uploaded to YouTube in July 2015 shows, among other horrors, fighters attacking statues and reliefs with sledgehammers. Gorgon and Medusa heads, attached to iron rods at great heights during the reconstruction of the façade, were also destroyed. IS propaganda offered the trademark justification: God ordered the dismantling of idols, pre-Islamic polytheism and the Western fetish of archaeology. In some videos, fighters fire salvos from assault rifles at the temples. (Walter Andrae had previously reported that some ornaments on the façades had been damaged by “shotgun blasts”, so the vandalism of the IS enjoyed a certain precedent.)

Many original statues and reliefs were irretrievably destroyed by the jihadists, especially since they struck not only in Hatra but also in the Mosul museum, where some of Hatra’s treasures had been taken for display and examination. However, Hatra may still have been lucky. When government paramilitary units drove IS out of Hatra in 2017, they found parts of the area mined. However, contrary to all fears, the Beit Allaha and the Hellenistic Sun Temple, which dominate the scene, had been neither blown up nor bulldozed to the ground. Did the jihadists lack the resources to stage a major doomsday operation out here in the remote steppe? Or were IS commanders and their supporters, some of whom came from the surrounding area, secretly appreciative of the queen of the desert, or even fearful to release Hatra’s demons? IS leadership included former officers of Saddam Hussein's intelligence services, who may have remembered their master's affection for the site.

For sure, like many far more learned visitors, they had no idea how much they should have hated Hatra's splendid ruins. For this was not the palace of a desert prince. This was a pantheon, a monument of religious tolerance and diversity like no other in the Middle East.