The “City of the Dead”, Egypt’s famed necropolis and home to thousands, is earmarked to make way for a highway project. After backlash from locals, authorities will have to decide: Which of the historic sites will stay, which will be moved – and which one will be lost forever.

At the age of 44, Hadith scholar Nafisa moved with her family from Mecca to ancient Cairo, or Fustat, as it was known at that time, and continued her academic career there. Among other things, the descendant of the Prophet Muhammad had a splendid apartment that even Muhammad Ibn Idriss Al-Shafi’i, founder of one of Sunni Islam’s four religious schools of law, frequented regularly, becoming one of her most famous pupils. She would influence the founder of the Shafiite school of law greatly, and besides their life-long friendship, their legacy as Egyptian scholars is visible to this day: Both are buried in the same graveyard on the outskirts of what was called Fustat in the early Abbasid era.

The cemetery itself is named after the female scholar. Around two centuries after their death, famed Fatimid general Jawhar Al-Siqilli laid the foundation of what would become Cairo, the foremost metropolis of the Arab world. With the capital growing rapidly, the “City of the Dead” became part of Cairo, and a landmark of the city, as “Sayyida Nafisa” and dozens of other cemeteries would be the final resting place for kings and imams, emperors, and authors throughout Egypt’s history.

Alas, those days have seemingly come to an end. The necropolis, nowadays comprised of a northern and a southern cemetery, each extending over several kilometres, is about to vanish in its current state, making way for the extension of Salah Salem Highway. At the end of May, a notice of eviction by the Egyptian authorities reached the owners and relatives of the graves by letter and mail. A few days later, construction cranes began wrecking stones. However, even after demolition started, it is still not clear, which sites will be relocated to the south of Cairo, which one will be preserved on site, and which are up for permanent removal.

Some of the historic mausoleums, such as Al-Shafi’i’s sanctuary, will remain untouched. The mausoleum of Farida, the wife of King Faruq I. (1920-1965), on the other side, will be demolished. At the request of her family, her remains were handed over to the authorities and will be buried next to her husband at Al-Rifai Mosque. The authorities have dealt much more ruthlessly in more recent burial sites: Construction workers were told to dig out corpses are laying underground for less than a year.

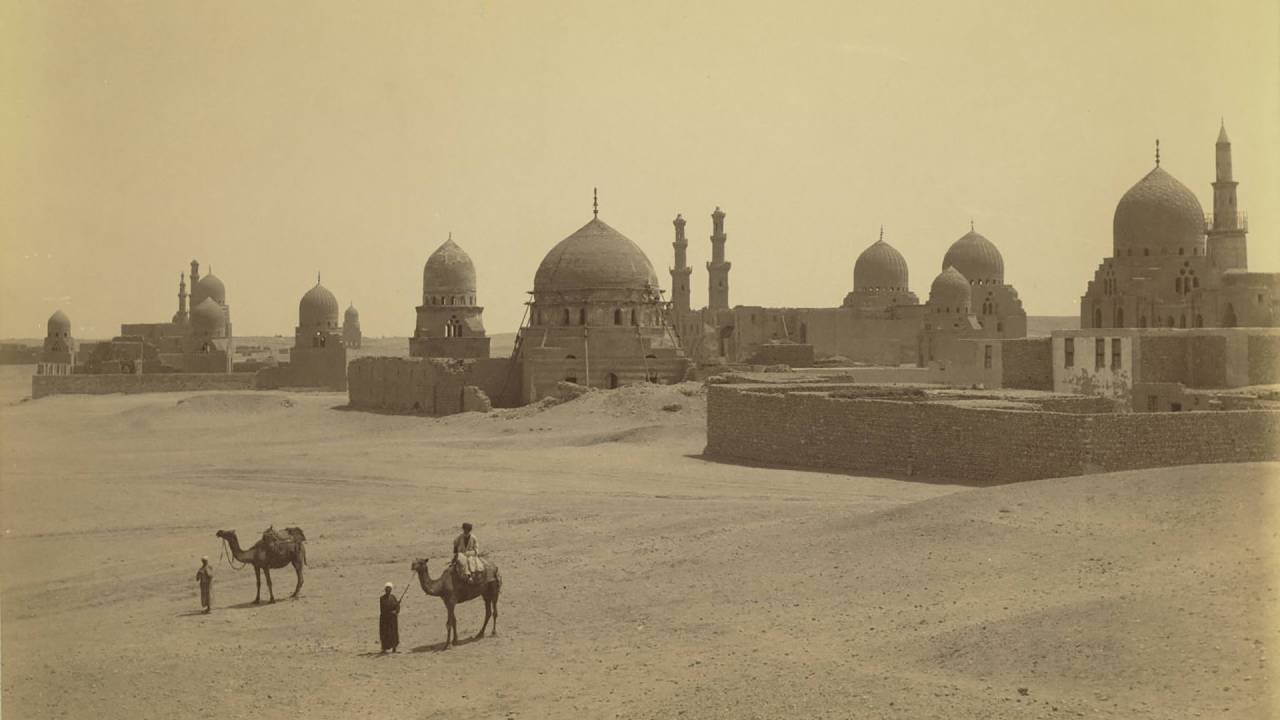

The UNESCO World Heritage site has always been a place for commemorating the country’s history – for Egyptians and foreigners alike: Scholars and travellers have been deeply impressed by the “City of the Dead”. Bernhard von Breidenbach, a 15th century German legal scholar and pilgrim, noted in his diary when arriving in Cairo: “There are large cemeteries founded for sultans, princes and Arab nobles, and magnificent buildings of marble and other high-end stones are built elaborately. I have not seen similar splendours in Christian cemeteries”.

As he further explains, it appeared to him that the Mamluks, Egypt’s ruling class at his time, were longing for tranquillity in a deserted place, far removed from the beauty of green gardens inside the city. As he writes: “Here, where they fall into their last sleep, the former rulers are guarded themselves – by minarets and domes topping the graves”.

And yet, the “City of the Dead” is a bit of a misnomer, as it is very much alive and inhabited. According to official statistics, about 300,000 people call the “City of the Dead” home. All over Egypt, about two million people live in cemeteries, most of them for lack of other viable alternatives.

Cemeteries as living quarters has not always been an expression of poverty in the country – quite the opposite. The tradition of people inhabiting graveyards goes back to ancient times under Pharaonic dominion, when Egyptians were praising and blessing death and its victims. The country has been experiencing a long history of erasing and re-inventing these traditional cults by local communities.

And it is the locals who are now pushing back against the erasure of their cultural heritage. Weeks before the scheduled demolition end of May, the government claimed that media reports about Sayyida Nafisa’s imminent destruction were “distorting the facts.” While construction work was ongoing on site, resistance built up and led President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi to intervene a week later. Reacting to the widespread uproar, Sisi announced the formation of a committee headed by the Prime Minister, which is authorized to collect relevant archaeological data, while consulting with engineers on site. Ultimately, the fate of the Sayyida Nafisa complex is to be re-assessed, although no definitive decisions have been announced as of late August.

Meanwhile, the authorities are claiming that all archaeological sites on the cemeteries will remain intact, as they are subject to the Antiquities Protection Law No. 117 of 1983, which criminalizes any act that damages or destroys archaeological heritage. However, critics argue that most of the antiquities in the “City of the Dead” are not officially registered.