The recent attack on al-Hasaka prison shows that the Islamic State group (IS) could be staging a comeback. French Syria expert Fabrice Balanche explains the new strategy of IS and how Turkey is trying to take advantage.

zenith: The breakout attempt at al-Hasaka prison, where a lot of IS prisoners are interned, was the biggest attack since the end of the caliphate. What exact circumstances allowed this to happen?

Fabrice Balanche: IS was able to infiltrate the Arab neighbourhood of al-Hasaka – thanks to some kind of Omerta. IS could rent rooms and move around the neighbourhood without anyone telling the police.

Does IS still have the support of some parts of the local population?

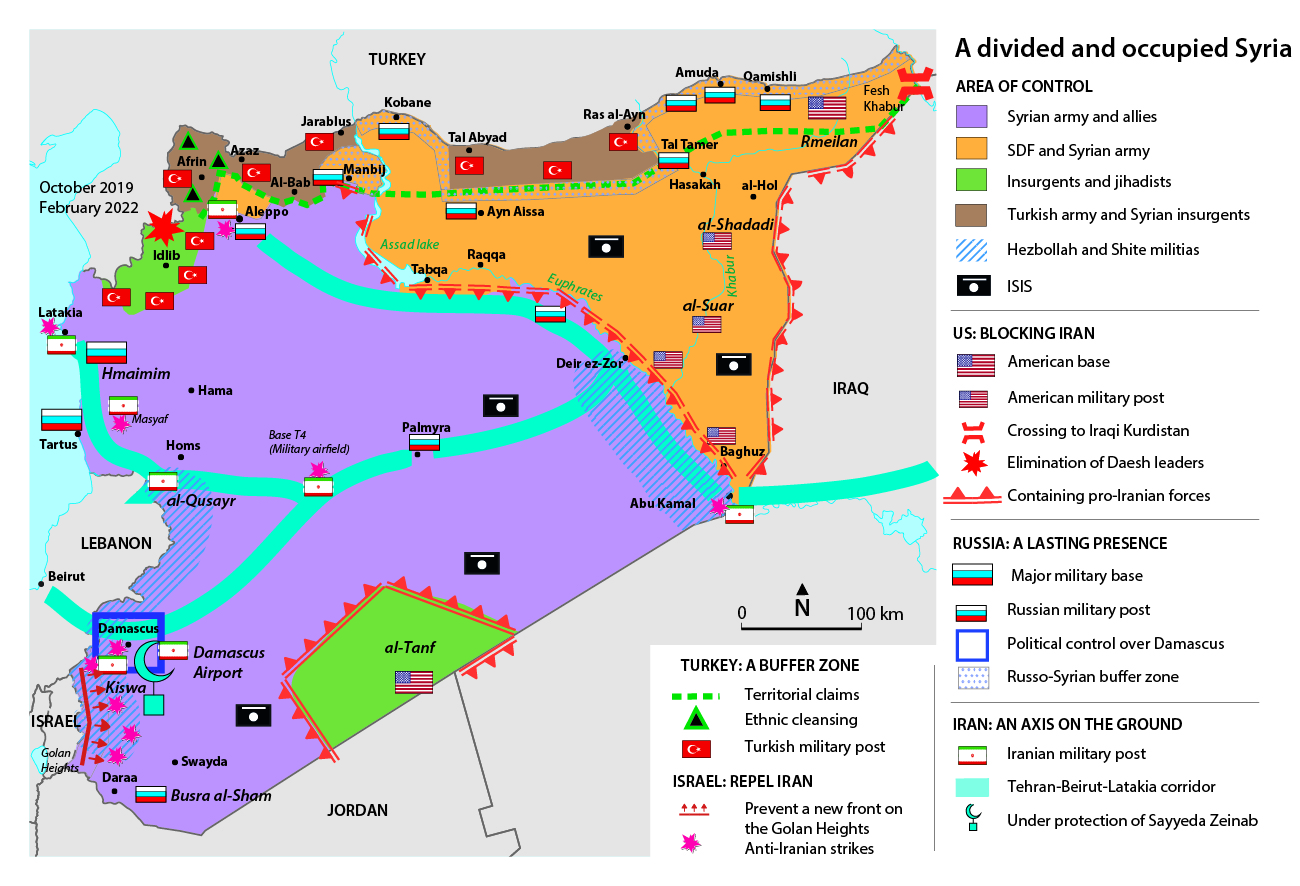

I spent one month in north-eastern Syria. When I visited Raqqa, Deir ez-Zor, Kobane and Qamishli, I was very surprised by the nostalgia for IS among the Arab population, with people telling me how they used to have ample access to electricity and fuel. Also, the economic situation wasn’t the total disaster it is today. The borders are oftentimes closed, making trade between Syria and Iraq difficult. People are feeling nostalgia for better economic conditions under IS rule, but the Arab population also has difficulties accepting being ruled by the Kurds.

How probable is another breakout attempt in north-eastern Syria?

About 10,000 IS fighters and thousands of their family members are imprisoned. The current goal of IS is to liberate these people. It’s also important for the group to show strength by breaking these people out, so it will renew its attacks on prison camps.

The Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and the US worked very closely combatting the prison break. Does the threat of a resurgent IS hail closer cooperation between the US and the SDF?

This prison break made the US and the West in general wake up. People in the West thought that the SDF is taking care of the IS prisoners for them. The Western countries failed to repatriate IS fighters and the danger of a renewed IS threat was essentially forgotten. The Western countries also barely provided assistance to the SDF, even tough north-eastern Syria is grippled by Turkish attacks, as well as a financial crisis.

What has changed after the attack on al-Hasaka?

In December, the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) closed the border crossing to Syria, even though it is a major trade route for north-eastern Syria. When the fighting in al-Hasaka started, the US pressured KRG Prime Minister Masrour Barzani to reopen the border. The US reckoned the SDF couldn’t fight IS if the economic crisis wasn’t somewhat alleviated. This attack proved that a strong cooperation with the SDF is still necessary. The Kurds are fed up with the arrangement of securing IS prisoners for the West. They risk their lives to keep our terrorists locked up. So they expect some sort of support. If the Western countries don’t want to repatriate their jihadists back to Europe or the US, they should at least be willing to share the burden of the fighting.

Christians in Qamishli have been deeply opposing efforts to impose the Kurdish language on them. Does the SDF still enjoy the support of the Christian communities of north-eastern Syria?

The Christian communities in Qamishli originally were more on the regime side of the conflict. They opposed the idea of Kurdish separatism because they supported Syrian nationalism. They also later on very heavily opposed Kurdish-language school programs. In 2017, the administration, dominated by Kurds, wanted to impose a new Kurdish-language curriculum in Kurdish areas. Christian kids could still visit private Christian schools, which teach the official Syrian curriculum in Arab. However non-Christian Arabs weren’t allowed to visit private Christian schools anymore and had to visit Kurdish schools.

What was the issue with these changes to the school system?

There are only a few secondary schools in north-eastern Syria, so many parents look for alternatives in regime-held territories. However, Kurdish diplomas are not recognised there, while those of private Christian schools are. Because people have the educational opportunities for their children in mind, the non-Kurdish communities tried to push back against these changes.

Has the relationship between the SDF and the Christian communities improved?

The administration quickly renounced its changes to the school system after facing popular backlash. In addition, the relations between Arab tribes and the administration have also improved. The Kurdish-led administration has learned to be more flexible toward the local community. One example: at the beginning of 2017, the Kurds wanted to put an end to the practice of polygamy. However, the administration then reversed course and doesn’t interfere anymore.

What role do Christian militias play within the SDF?

A very small one. The Sutoro militia is one example: over 90% of its members are Muslim Arabs or Kurds, with only very few Christians serving. Because many Christians have fled Syria. In Hasaka province, the Christian population has shrunk from 10% to 2%. Most young people that would normally fight within the militias have fled to Europe. So Christian militias are mostly symbolic.

If the Christian militias only employ a small percentage of Christians, what purpose do they serve?

In north-eastern Syria the three official languages are Kurdish, Arabic and Syriac, the language of Syriac Christians. The Kurdish administration wants to showcase the involvement of Christians in the political process, in government and within the SDF. Those who are perceived as protectors of the Christian community in Syria, are more likely to get support from the West.

Have you witnessed Turkish attacks when you visited north-eastern Syria?

Turkey is still shelling the Kurdish side from army positions in Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ayn. The extreme north-east of the SDF-held territories, near the border with Iraq, are also attacked. Turkey wants to destroy the confidence in the administration of north-eastern Syria. The shelling doesn’t kill many people. Its purpose is to destabilize. The attacks are supposed to instil fear, force the population to flee and to block investments. I visited Kobani four years ago. It was a dynamic city in the middle of reconstruction. People were coming back from Iraqi Kurdistan because of job opportunities. Today, Kobani is a dying city.

IS leader Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Quraishi was killed by American Special Forces on February 3rd. What role did he play within the organisation?

After the death of al-Baghdadi in October 2019, he became the supreme leader of IS and he reorganized the group. He planned operations like the Hasaka prison break. IS is currently not planning to directly control territory anymore, like it used to between 2013 and 2018. Quraishi instead focused on the reorganisation of its financial network.

Is this just a transitory phase or does IS intend to not hold any territorial control again?

After the collapse of the so-called caliphate, IS understood that the time wasn’t ripe for them to hold their ground. The military supremacy of the US and Russia makes this impossible. Their Kalashnikovs have no chance against airstrikes. IS plans to stay underground and to target their enemies with guerrilla attacks. This also makes it easier for them to rebuild their organisation. It’s a strategy similar to that of al-Qaida.

Were any other countries than the US involved in tracking down Quraishi?

Quraishi was hiding only a few kilometres away from the Turkish border in Idlib. 9,000 Turkish soldiers are stationed in Idlib and Turkish intelligence is very active in the region. Turkey probably knew about Quraishi hiding in Idlib and handed the information to the Americans.

What did Turkey get in return?

In 2019, Trump withdrew American troops from Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ayn, two days later Turkey attacked the area and three weeks later the US killed Baghdadi. If we keep the implications of the events of 2019 in mind, we should ask today: did the US give Turkey green light for an attack on the Kurds in exchange for information on Quraishi’s location?

Is Idlib a safe haven for IS militants?

The area not a 100% safe for them. Many former IS fighters moved to Idlib after Raqqa fell in 2017. Those were mostly foreigners. They came to Syria to join the jihad and later on used personal contacts to join other Islamist groups like Jabhat al-Nusra, today known as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham.

How easy is it to pass through from north-eastern Syria to Idlib?

If you have money, you pay smugglers and they arrange a transfer. At the border, anything is possible.

Is IS also staging a comeback in regime-held territories?

I haven’t seen it with my own eyes, but what people have told me is that the situation there seems even worse. The economic and the security situation in general are worse. The Syrian army is being targeted by IS fighters. When I was there, near the border in Deir ez-Zor, IS attacked and killed Syrian soldiers using heavy smoke to disguise their advance. IS is stronger in the regime-held areas because the Syrian army isn’t as capable in terms of anti-terror operations as the SDF. That’s why IS prefers to stay in regime-held areas because it is less dangerous for the group.

Is IS also staging a comeback in Iraq?

Mosul, a predominantly Sunni city, is under Shia occupation and that’s unacceptable for Arab Sunnis. The Institute for the Study of War estimates that the group has up to 15,000 fighters in Syria and Iraq at its disposal. IS is able to recruit a new generation of militants, who are frustrated, have no hope, no future, no jobs. So they join IS.

Fabrice Balanche is a geographer and political scientist teaching at the University of Lyon. He is also a Fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.