Iran and Saudi Arabia are fighting for supremacy in the Middle East. At least most European media outlets constitute this narrative. But is this really the true situation?

German-speaking journalists writing about the Middle East love the word ‘supremacy’. Apparently politicians, experts and journalists can no longer discuss conflicts in Syria, Lebanon, on the Arabian Peninsula, in Palestine, Egypt, Yemen or Libya, without mentioning that Iran and Saudi Arabia are fighting for supremacy over the Middle East.

Are they really doing that? Is anything being explained with this sentence? Or is this mantra used to obscure the fact that in Germany hardly anyone wants to publicly analyse the role of Israel in the region? What is supremacy? In German-speaking countries, the last struggle for supremacy was fought between the Habsburg and Hohenzollern dynasties. But in that case, both noble families wanted to rule alone over the whole region. In today’s Middle East, nobody is accused of wanting to eat the cake alone. So the search for a historical parallel in Germany’s past is likely to be misleading.

The quest for supremacy in today’s Middle East confrontation would be more intelligible if it meant only the global dispute between the US and Russia. The US began supporting the Syrian opposition after the initially peaceful demonstrations against President Assad, with the intention of reducing Russian influence in the region. Players in Washington asked how Russia could act as a global player in the Middle East, this country whose GDP is dwarfed by the state of California. Today we know that the US has lost this battle for supremacy, at least with regard to Syria.

At the purely regional level, it remains an open question what can be won or lost with a victory or defeat in the so-called battle for supremacy. Which criteria measure whether influence on neighbouring countries is increasing or decreasing? In terms of financial resources, Saudi Arabia would be in the lead; in so-called human resources it would be Iran – probably also the leader in military clout.

But at none of these levels has there been a direct confrontation. Nor is it recognisable how a change in social and political power relations should lead to the dominance of one state over the other. And religiously, the Sunni would not replace the Shia or vice versa, even if one of the two countries completely conquered the other militarily.

Even a historical review of the region does not help. There are two notable cases. Before the founding of the state of Saudi Arabia, the Saud Bedouin tribe, driven by hunger for pre-eminence, led successful wars of conquest against almost all the other tribes of the Arabian Peninsula. But this was not a crisis between states.

The other case is the Iraqi attempt under Saddam Hussein to increase his power and financial resources through wars against Iran and Kuwait. These failed ventures, however, were primarily attempts at military conquest and only secondarily at regional supremacy. Therefore, the two notable cases in the region do not allow relevant, instructive conclusions.

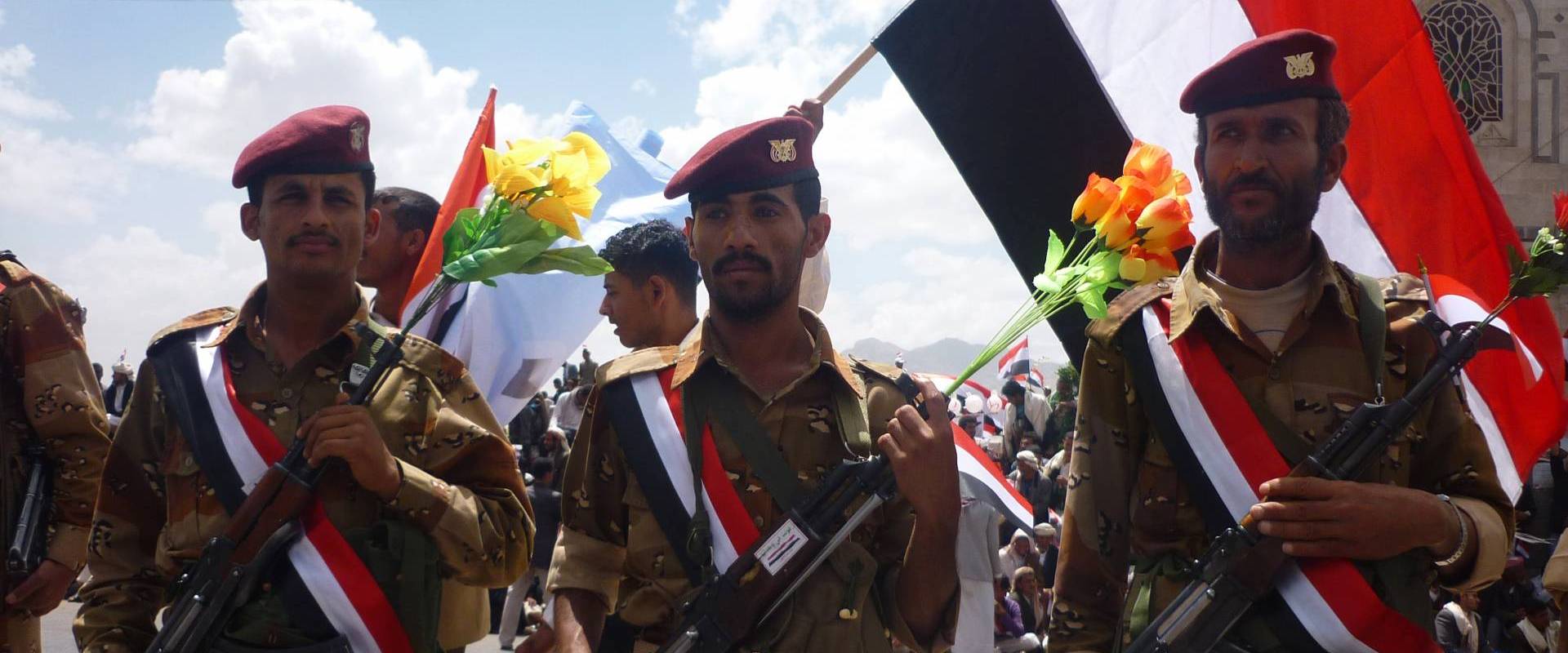

In spite of all this, it is obvious that tensions between Iran and Saudi Arabia have not only increased, but that they manifest in proxy wars whose inhumanity has not been mitigated or stopped by mediation. The struggles in Yemen, Iraq and Syria, with or against Al Qaeda or ISIS, the prospect of a new civil war in Lebanon – these show that decision-makers in Riyadh and Tehran find these tensions extremely threatening.

What fuels this perception? The words ‘pursuit of supremacy’ apparently cannot answer this question. A different historical background may provide the terminology to comprehend this strong sense of being threatened.

In 1953 Iran witnessed the overthrow of the democratically-elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh by a military action of US and British intelligence agencies. Shah Pahlevi was seen as kind of US proconsul. This is why the ayatollahs’ revolution gained popular support. Entrusting power to the clergy rather than to a hereditary monarchy was seen as an act of sovereign self-determination. In April 1980, the US attempted to liberate the hostages in Tehran’s American embassy with a failed commando operation. More recently, Iran was placed on the axis of evil. The assessment, traumatic in Iran, was that the US was pursuing regime change.

On the other side, Saudi Arabia’s history of becoming a sovereign state is completely different. Only the regulation of religious life was entirely left to the clergy of the Wahhabis. Secular power lay exclusively in the hands of the Sauds, first in the state’s founder Ibn Saud, later in his descendants.

This has not always been uncontroversial. Before Ibn Saud could crown himself (after the expulsion of the Hashemites from Mecca in 1932), he had to overcome the most difficult obstacle – in 1926 he was confronted with the uprising of several tribes that had taken on the demand of the Muslim Brotherhood that secular power should be exercised by spiritual leaders.

The antagonism between these different principles of government in Iran and Saudi Arabia can best be illustrated in the following way: If today’s Iranian ruling system were introduced on the Arabian Peninsula, it would be the end of the royal house there.

If the Saudi system were to be established in Iran, then a Shah would reign there again.

After Saddam Hussein’s attack on Kuwait, Saudi Arabia came under the protective umbrella of the US - after Kuwait, in almost no time, the Saudi oil fields would have been conquered. But in Tehran, this close relationship with the US was perceived as an announcement of the next attempt to bring about regime change in the Islamic Republic.

Iran has repeatedly complained that the Shiite minorities in Bahrain and eastern Saudi Arabia are being hindered in their freedom of worship. Each time such accusations are heard, alarm bells ring in Riyadh (the Shiite minority live in the east of the country, where the largest oil reserves can also be found). Terrorist attacks, an uprising leading to civil war, even a secessionist attempt to create a Shiite state around Dhahran - these would plunge the kingdom into an existential crisis.

Aggressive attitudes often originate in the perceived necessity to defend yourself. Perhaps it is only on the basis of this analysis that we can think about what the beginning of a détente might look like. Iran and Saudi Arabia have historical reasons for taking threat signals seriously. Both are closely embedded in relationships with each other’s great power, which in turn are antagonistic to each other.

However, this does not exclude the possibility that in both countries a new assessment will mature in the foreseeable future: Confrontation does not only bring advantages. Political costs should also be taken into account. In many parts of the world, Islam is no longer perceived as peaceful. If the two largest states in the Islamic Middle East jointly made visible their willingness to coexist, then it would be very difficult to blame their religion for increasing instability in the region.

Perhaps such a willingness could be expressed in words that speak concretely of what inspired previous confrontations. In times when wars were still regarded as a continuation of politics by other means, one might have spoken - as a reassuring counter-recipe - of the possibility of a non-aggression pact, like the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928. Nowadays, in addition to military threat, there are subtler ways to foment an opponent’s fears. The danger cue is ‘regime change’.

So. Let us imagine for a moment a Saudi king and a Grand Ayatollah agreeing that their policy towards the each other could be summed up as: ‘No regime change.’

That could work wonders. Both countries have received a lot of criticism in the past. Rightly or wrongly, together they must aim to cultivate the reputation of their countries and their religions. Specifically, foreign investment and technological know-how would be attracted more easily if less political risk had to be priced in. The names of the two heads of state would stand for a historic event - for the beginning of a period of regional pacification and cooperation. They would become symbols of the real sovereignty of their countries, even against the whisperings and resistances of greater powers.

A policy they would have initiated themselves.

Dr. Gerhard Fulda, Ambassador (ret.), Berlin, is Vice-President of the German-Arab Association (DAG) and a founding member of the League for Bringing an End to Israeli Occupation.