Nawal El Saadawi wrote about many issues deemed controversial, including virginity, sexual abuse, and prostitution.

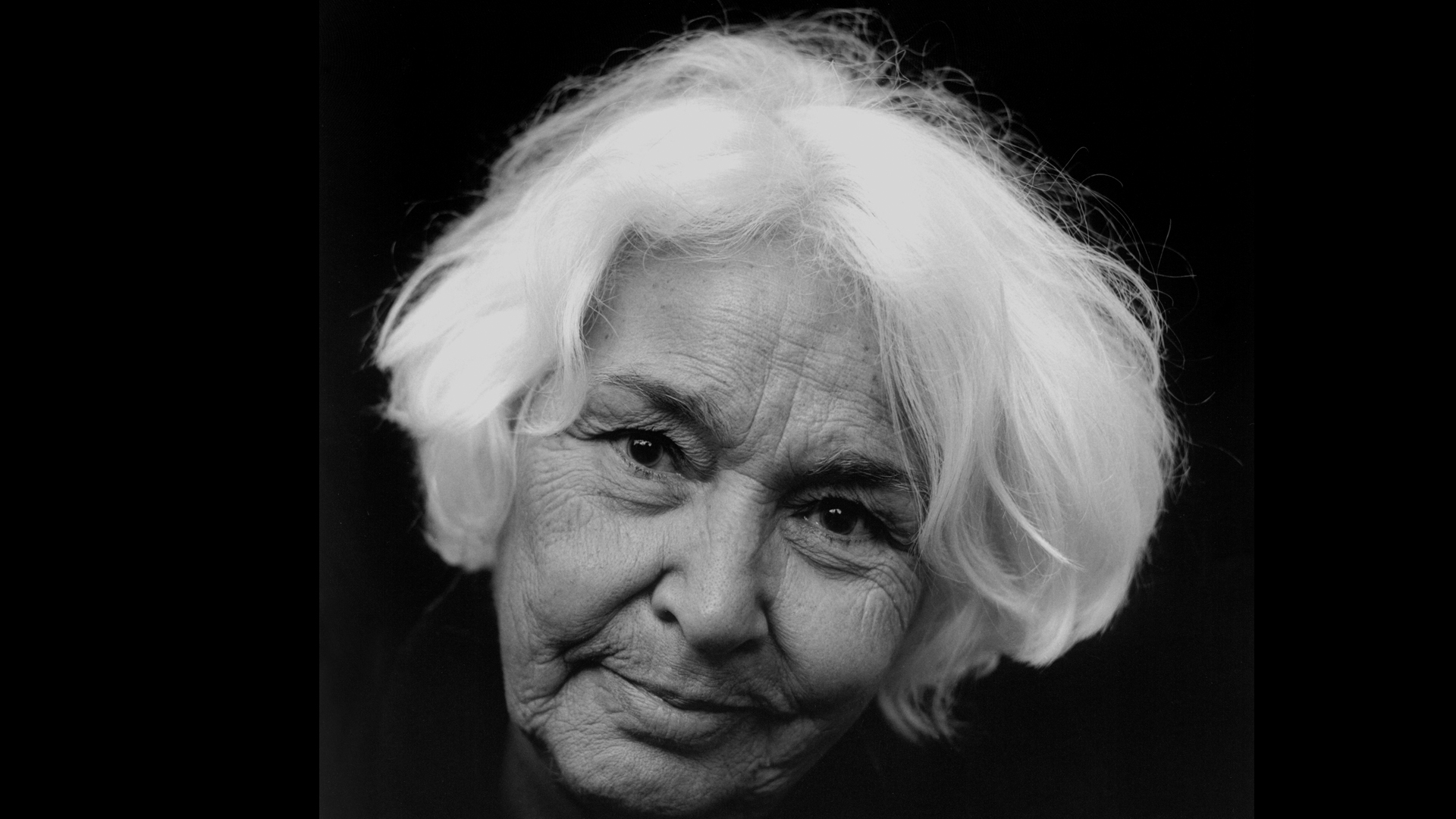

The world has lost one of its most outspoken defenders of women’s rights. The Egyptian writer, medical doctor, and activist, Nawal El Saadawi, has passed away at the age of 89 in Cairo on March 21, Arab Mother’s Day. People around the world have been commemorating her death. One reader wrote “you left the life that we live, my saint, on Mother’s Day, as if you wanted to reassure us, as mothers, that you are the spiritual mother of the women and girls of our generation.” A sentiment shared by many who saw her as an inspiration.

Born in the village Kafr Tahlan in the lower Nile Delta October 27, 1931, El Saadawi graduated as a medical doctor in 1955 and practiced as a physician in rural Egypt. There she often treated young girls who were injured as a result of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). She herself had undergone FGM at the age of six.

In the “Hidden Face of Eve”, which was first published in Arabic under the title “The Naked Face of the Arab Woman” in 1977, she describes how she was dragged out of her bed one night and carried into the bathroom, how she felt the cold tiles on her naked body, and how her mouth was covered while undergoing the procedure.

She describes the incredible physical pain as well as the shock when she spotted her mother standing among the smiling crowds. It was a defining moment for her that turned her into a life-long campaigner against FGM, which was criminalized in Egypt in 2008 but remains widespread.

El Saadawi pointed to two philosophical and theological trends in the Islamic tradition that uneasily sit together

Her childhood remained a defining period that she would revisit in many of her writings. El Saadawi states that her parents were both educated. Her father was a university graduate and served as a General Controller of Education for the Province of Menoufia in the Delta region. Her mother was French-educated. She says that her mother used to say that boys and girls are equal, but that she constantly felt being less. She observed her aunt being slapped in the face for giving birth to three girls and her uncle threatening to divorce her should she ever give birth to a girl again.

She would later write that from the moment she opened her eyes she felt that the utterance of the word “bint” (girl) was almost always pronounced with a frown. She describes how her grandmother once told her that it would have been better had she been born a boy like her brother. Her accounts demonstrate that women were not only victims. They are instrumental in upholding the patriarchal order; in the end patriarchy works most effectively if the suppressed believe in the legitimacy of their own subordination.

El Saadawi wrote about many issues deemed controversial, including virginity, sexual abuse, and prostitution. She showed that separation of the sexes, concepts of morality, religious extremism, economic deprivation, and limited physical space lead to different forms of abuse. She pointed to two philosophical and theological trends in the Islamic tradition that uneasily sit together: a positive attitude towards sexual pleasure and fulfillment but viewing the sexual power of women as a source of fitna, strife.

Her activism and the taboo topics she spoke about brought her in confrontation with the Egyptian regime as well as other social conservative actors

According to El Saadawi, girls are brought up to know that their sexual organs are taboo, and that their honour and the honour of their family depend on their virginity. “She loses her honour and virginity. The man never loses anything.” The concluded that, a society where sexual relationships outside of marriage remain taboo while the economic hurdles of marriage remain high ultimately leads to sexual frustration.

Her activism and the taboo topics she spoke about brought her in confrontation with the Egyptian regime as well as other social conservative actors. In 1972 she lost her job as Director of Public Health at the Egyptian Ministry of Health when her first book “Women and Sex” was republished after having been banned for over two decades.

She was critical of the Sadat government which consciously worked to strengthen Islamist actors in the 1970s as a counterbalance to leftist opposition. She was briefly jailed as an enemy of the state during the presidency of Anwar Sadat in 1981 but released after his assassination in October of that same year.

Appreciated and celebrated in Western countries and a frequent speaker at Western Universities, El Saadawi was also critical of how the story of “the” Arab woman was often woven into a single narrative. In an article for the Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies, she complained that a book was only seen as marketable if it showed that “tyranny or masculine violence is a Muslim genre”.

That market did not tolerate comparisons to the suppression of women in Christianity or Judaism and it could not stomach resistance to Western intervention in Iraq or support for Palestine. She complained about how publishers in Germany or the United States would change the titles of her works or use veiled women on the cover to attract a bigger audience.

El Saadawi advocated for international solidarity among women, but she grappled with the question of how such solidarity could be exercised

She criticized the portrayal of the discrimination Arab women face as a result of culture and religion without taking political and economic factors into consideration, and debunked this attitude as hiding the imperialist project that contributes to the very economic exploitation and underdevelopment that also significantly affects women.

For El Saadawi women’s rights were ultimately political, and political and economic emancipation went hand in hand. Full emancipation meant freedom from all forms of exploitation including economic, political, sexual or cultural. El Sadaawi emphasized that the oppression of women was in no way characteristic of Middle Eastern countries alone but indeed a world-wide phenomenon, with just its manifestations differing from context to context. She was eager to stress that “feminism was not invented by American women.” It was not a concept of the global north that had merely been received by the global south; feminism was actively shaped by the global south.

In the end, her fame in Europe and the United States was also likely also due to the fact that she wrote about topics that resonated with images held by Western audiences about “the” Arab woman. Ultimately, it was challenging to strike a balance between radical honesty and an unapologetic account all the while not confirming existing stereotypes. A challenge many scholars who are not comparativists and who write about issues concerning women in the global south face.

El Saadawi advocated for international solidarity among women, but she grappled with the question of how such solidarity could be exercised. She emphasized the importance of an understanding of the particular contexts people operate in. If the specific context is not taken into consideration, “enthusiasm and the spirit of solidarity on their own may lead feminist movements to take a stand that is against the interests of the liberation movements in the East, and therefore also harmful to the struggle for women’s emancipation.”

Solidarity was and ultimately remains only possible when acknowledging commonalities as well as differences, focusing on underlying causes of submission and discrimination, and by acknowledging the humanity of the other and meeting them at eye level – a reminder that resonates today.

In 2011, she joined the protests on Tahrir Square against the Mubarak regime, but was critical of the political developments that followed

Many of the issues she touched on remain relevant today in Egypt and beyond. El Saadawi had pointed out that women’s participation in the job market, the public sphere, does not necessarily translate to equality in the home, the private sphere. She observed that women had entered the job market as well as politics, but ultimately remained unequal in family law.

The Covid-19-pandemic has thrown this fact into sharp relief as the overwhelming burden of home schooling, housework, and child care is falling on women; violence against women has surged throughout the world. Meanwhile in Egypt a controversial draft family law was published February 23rd which has been heavily criticized by the Egyptian Centre for Women’s Rights for treating women as legal minors.

El Saadawi remained politically active throughout her life. In 2011, she joined the protests on Tahrir Square against the Mubarak regime, but was critical of the political developments that followed. When the Muslim Brotherhood won the first post-Mubarak elections, she accused them of hijacking the revolution. After the military coup of Abdul Fatah al-Sisi in 2013, she became a supporter of the Sisi regime. In a BBC Arabic interview in 2018 she accused the Western media of smearing the image of al-Sisi.

Saadawi’s defence of the Sisi regime and her failure to condemn the human rights violations committed by it are a sharp break with her previous decades-long track record of opposing illegitimate political power. Questionable as this stance may have been, it does not negate her achievements, her sacrifice, and the impressive body of work that she has left the world.