Idlib has been on the Assad family’s hitlist for decades. The assault on the province may have come to a fragile halt, but history suggests that it is only a matter of time before the former ophthalmology graduate trains his eye on Idlib once again.

Idlib once attracted visitors from the world over. They were drawn there by the province’s landscapes replete with even-green olive groves, cherry orchards, fig trees, and hundreds of historical sites. I was born among all this beauty in 1969, a year before Hafez al-Assad became Syria’s president for life. One whole without an Assad in power, before our carefree life in Idlib was slowly suffocated by tyranny and oppression. Assad seizure of power in a coup orchestrated by army officers and Baathists foreshadowed a raft of drastic changes to the country’s political, economic and social structures. Those who refused to participate in the coup were purged. Some were imprisoned, others deported or simply killed.

In 1970 Assad began touring Syrian provinces to legitimise his power grab, and Idlib was on the itinerary. When he came to the city, he chose to deliver a speech from the balcony of one of the city centre’s most ostentatious buildings. Those who gathered below, instead of listening to Assad’s populist bluster, threw shoes and tomatoes at their self-described leader. The crowd was too numerous to disperse by force, so Assad was forced to scuttle away seething with rage for this small province.

As a schoolchild, I was forced to glorify Assad. We were led onto the streets and told to shout "Long live the president” and “We sacrifice our blood and souls for you, Assad.” When I got home from school, I would hear by father criticising Assad’s dictatorship. I could not understand why he was so unhappy about someone who our teachers described as Syria’s “unique eternal leader”. During the 1980s, Assad stalked his remaining opponents, both real and imagined, throughout the province. Meanwhile, both public services and the local economy continued to deteriorate, but just by mentioning this you could be branded ‘an opponent’. Opponents were arbitrarily arrested, and few re-emerged from Assad’s prisons.

Then there were the massacres. On 9 March 1980, Assad’s forces entered the town of Jisr al-Shughour in the west of the province. They lined up dozens suspected of being members of the Muslim Brotherhood against a wall and shot them dead in public. The repression in Idlib though was not on the scale of what happened in Hama, where in 1982 Hafez’s brother, Rifaat al-Assad, conducted a military operation following anti-regime demonstrations in which around 40,000 were killed.

I did not give any of this much thought back then. It was 1987. I had just finished secondary school and I was brimming with patriotism and youthful vigour. So, I decided to sign up as an army officer. I sailed through the required tests, yet I was not accepted. I had no idea why. When I asked my father, who was then a police officer, he told me that Assad’s military would never accept officers from Idlib or Sunni communities. I had not understood how Assad exploited sectarian divisions to stay in power. Only those who pledged total allegiance to Assad and his ruling figures had a chance at achieving high office.

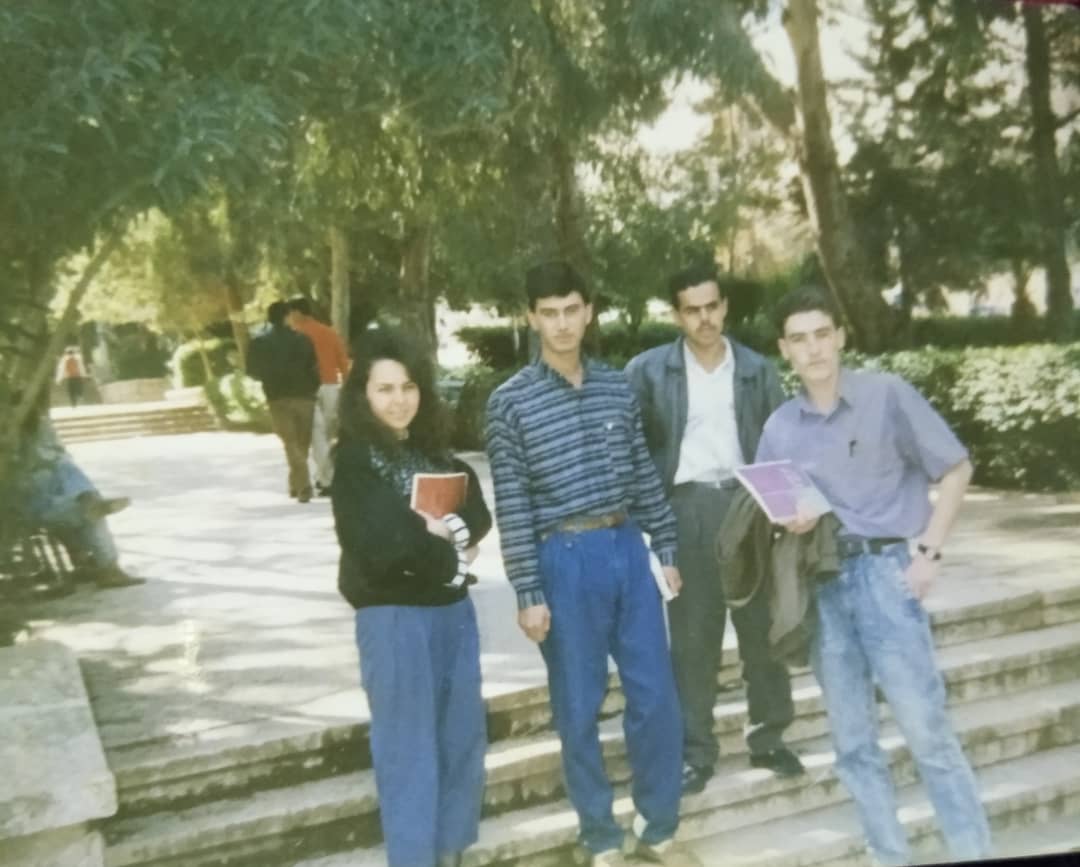

The massacres of the 1980s gave way to a decade of increasing economic hardship. For my part, I put aside my dreams of joining the army, and busied myself with studying English literature at the University of Aleppo. Those who spoke out were soon silenced by Assad’s ever-tightening grip. All hope seemed lost. Then, on 10 June 2000, Assad died. The young Assad carried on in much the same vein as his father. Hafez may have given way to Bashar, but in Idlib not much changed. The intelligence services remained as ghosts who controlled to minutiae of daily life in the province. The anger that brewed in the hearts of Idlib’s inhabitants, could not be seen on their faces. I was not alone in thinking that the Assads would reign over Syrians forever. Though fires smouldered beneath the ashes. Awaiting a breath to catch ablaze.

I witnessed first-hand how eleven demonstrators were shot dead in a matter of minutes.

When the revolutions of 2011 began to creep over the Arab world, I was afraid that Syria would remain unaffected. To minds haunted by the massacres of the 1980s, rising up against Assad was inconceivable. I could not have been more wrong. When, in March 2011, demonstrators filled the streets of Daraa demanding the downfall of the Assad regime, Idlib was one of the first to echo their calls for dignity and freedom. I was among them. We had waited a lifetime to speak our minds. Not long after I was on my way to the university where I was teaching English, when I was arrested by Assad’s men. To them I was in a position to silence my students. I was only released under the condition that I would help to supress dissent in my village of Kurin, whose inhabitants were among the most vociferous critics of Assad. Their harassment of me nonetheless continued. Both my wife and I were soon fired from our jobs.

In May 2011, Assad deployed most of his army throughout Idlib. Tanks and checkpoints began to fragment the province as the regime ramped up efforts to muzzle its inhabitants. Assad was consulting the old playbook by attempting to mobilise the Druze minority in the north of the province. But Druze leaders refused to comply and offered safe haven to those displaced by Assad’s violence. Then the massacres began. The first took place on 21 May 2011 near the village of Al-Mastumah in the south of the province. Hundreds of thousands were marching north from the town of Ariha to the city when security forces ambushed them. I witnessed first-hand how eleven demonstrators were shot dead in a matter of minutes, and dozens more were left injured.

A week later, when the same thing was attempted in the town of Jish al-Shughour, the demonstrators fought back and some soldiers defected to join their ranks. It was a seminal moment. It demonstrated how the revolutionary movement was gradually morphing into an armed confrontation with the regime. Those who had defected started calling themselves the Free Syrian Army (FSA), then some extremist armed groups began to appear, such as ISIS, Jahbat al-Nusra, and Jund al-Aqsa. The latter, with the support of Turkey and Qatar, soon gained the upper hand throughout the province and by 2015 Idlib had fallen under their control. The FSA was side-lined, priorities shifted from freedom and democracy to those of an international jihadist vision, and the world turned away. For me, it was heart-breaking. For Assad, it was a boon.

It is not about the financial loss, rather it is the psychological stress of suddenly becoming homeless.

As the black banners multiplied, I continued to hold the green flag of the Syrian revolution aloft. Although, people like me were caught between the Assadist demon and sea of extremism engulfing the province. Assad went about systematically demolishing large parts of Syria. On 21 May 2015, it was my turn. I was lucky, though, my family and I were out when his warplanes reduced my home to rubble. It is hard to express how one feels when one’s home is destroyed. It is not about the financial loss, rather it is the psychological stress of suddenly becoming homeless. We were one among many families who lost everything in seconds. How can Syrians forget these atrocities and begin again when the war finally ends?

On 16 November 2017, my son, Ahmad, who was studying medicine at the university where I once taught, was driving me into the city. By then. I had a new job translating for the Idlib Health Directorate. Suddenly two masked men on a motorbike appeared in our rear-view mirror. We turned pulled over expecting they would pass, but instead they opened fire. They aimed at the driver’s side perhaps thinking that I was at the wheel. Six bullets punctured the car’s exterior. It was a miracle that we survived.

They wanted to silence me. I regularly appeared on the BBC and Al-Jazeera talking about the true goals of the revolution. This was not only annoying for the regime but also for the extremist groups, both had reason enough to want me dead. I did not have to wait long before I was targeted again. On the morning of 18 January 2019, I got into my car and drove for 200m when it exploded. The car was destroyed, but somehow I survived, now with a body full of shrapnel, some of which is still there.

Those of us who survived are left to wonder what another Idlib might have been, and still could be.

My German friends, who slept in my house while reporting on Idlib, were stunned by the repeated attempt to assassinate me. They helped me get out of the country and get a visa to travel to Germany. It is from there where I write. As I do so, I am unable comprehend what horror have befallen my compatriots and me. Four million Syrian Idlib locals and internally displaced people still find themselves trapped in this small disaster-stricken province. It is the last haven for the Syrian revolution after Assad’s Russia-backed forces conquered all other areas.

In the summer of 2018, not long before I left the country, Assad’s forces pushed into areas in the south and south-eastern countryside of Idlib. Many villages and towns in Abu al-Duhur and Senjar were occupied by regime forces and their Russian and Iranian allies. The resulting displacement constituted an enormous humanitarian challenge for local and international organisations. What remains outside regime control, it governed by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which has been reluctant to engage Assad’s forces. HTS has also shown little desire to tackle Idlib’s crippling unemployment. Idle hands beget higher crime. What remains of the province’s liberal movement is very weak. Members have either fled, been arrested, or been killed.

Idlib is now the worst place to live in on earth. It is encircled – soon to be entombed – by the proxies of regional actors, who have wrestled control of the conflict from the regime and the opposition. Many analysts believe that the destiny of Idlib is intertwined with the final settlement of the conflict west of the Euphrates. Hospitals, schools and other public building lie in ruins. Half a million civilians have been displaced. Because the world turned a blind eye on what has happened in Syria, this small province now faces complete destruction amid an unimaginable humanitarian crisis. And those of us who survived are left to wonder what another Idlib might have been, and still could be.

Abdul Aziz Ajini, 51, left Idlib in July 2019 via the Bab al-Hawa crossing into Turkey and arrived in Germany soon after, where he and his family now have asylum status. He was born in the village of Kurin, southwest of the city of Idlib in 1969. He was previously an English lecturer at the University of Idlib, and a translator for the Idlib Health Directorate.